Katmandu To Base Camp

by Maurice P. Wilson

Thursday 4th April was D-day for the Y.R.C. contingent in Katmandu. Our Leader was soon on his rounds waking everyone from their slumbers. Even the coolies seemed to sense the importance of the occasion, for they began to arrive before 7 a.m. and quite soon the grounds of the Embassy were alive with an army of men. Loads had been weighed in the preceding days and Tallon was busy allocating them to the men. Each man was required to carry 60 lbs., but it was obvious from the time each man took to select his burden that they felt some 60 lbs. were heavier than others. Their suspicions, I must confess, were not ill-founded.

There were 113 of these men, ‘city-slickers’ as we called them, though two who acted as sirdars carried no loads. Since these two were of little use in any capacity, it was never clear why they came at all. A counter of three boxes was set up on the gravel path and each man solemnly came forward to receive his advance of pay . . . fifteen Nepalese rupees (17s. 6d.). Press photographers, as well as amateurs, were snapping everywhere.

After the storms of the preceeding days this was a beautiful morning and the disorderly cavalcade got under way at 8 a.m. We returned inside for breakfast, for the sahibs were to be spared the ordeal of walking the first eight miles, a Land Rover had been laid on for them. In the early afternoon our own little convoy made a dignified departure amid fond farewells and presenting of arms by the gurkha sentry at the gate. Further military honours awaited us only a little way down the road as we turned into the grounds of the Royal Palace, where we were asked to sign the book reserved for distinguished visitors. We could hardly complain of the formalities attending our departure.

We soon caught up with the coolies who had got no further than Bodhnath, where a few words from our Leader were necessary to induce further progress. We ourselves continued along the broken road to its termination at Sanchu. Here we were surprised to find a lone Englishman, Mr. Rosser of the London School of Oriental Studies, who invited us to his upper room where we partook of chicken, the bird being rent asunder after the manner of Henry VIII. By mid-afternoon all our porters had arrived and together we continued a short way up the valley to Sankhu Pheidi, there we camped, and from there our Himalayan adventures began.

The camp site was a green sward about the size of a bowling green, bounded on two sides by brooks. The boxes were pitched in the centre and tents on the perimeter. A fire was made and as darkness fell we sat down to a three course meal of pemmican, minced meat and pears. As the meal drew to its close Fox called upon the six climbing sherpas to select their sahibs. At first reticent, they suddenly rushed across to our improvised dining table each thrusting an arm round the sahib of his choice. This novel method of selection worked out as follows

Fox—Mingma Tensing. Spenceley—Lakpa Noorbu. Anderson—Lakpa Tsering. Tallon—Pemba Gyalgen. Jones—AngTemba. Wilson—Pemba Tensing.

We slept well that night and the camp was astir early the next morning. The coolies had found their own lodgings in nearby houses and were on the job before we were ready ourselves. Loads were made up and the column stepped over the brook and straight on to the wooded hillside. We climbed about 1,000 ft. before reaching the summit of the pass, which was crowned by a chorten. The track followed was one of the main trade routes of the country and we were constantly meeting Nepali bearing their loads of merchandise. Men, women and children all carried baskets slung from the forehead in the now well known manner. We passed through several villages and were naturally the objects of curiosity wherever we went. Work, play and even gossip all stopped as the procession passed by, while the buzzing of insects mterrningled with the whirring of the cine-camera.

We could now get some idea of the complexity of the Himalayan foothills. Ridge followed ridge in all directions and nowhere did there appear sufficient flat land to pitch a tennis court. The farming was primitive. Each hillside comprised countless terraces each about four yards wide. Along such a terrace a single ox pulled a wooden ploughshare. In similar manner, others tilled the ground above.

Below us we could see our destination, the Indrawatti. Always it seemed only another half-hour below but, in fact, it was mid-afternoon before we finally reached it, tired and very thirsty. Thirsty because although we had passed lots of drinking places, we eschewed all water unless it had first been boiled or sterilised with tablets. We camped that night on a little hill behind Balam Patti, under a peeple tree, overlooking the river. It was a beautiful site, even if the village belied its beautiful name, and we had a commanding view for miles of the silted bed of the Indrawatti, one of the seven sacred rivers of India.

The following morning the prospect of crossing the river caused a stir of excitement. Camera men were rushing about everywhere for the best point of vantage. It certainly was an impressive sight as the men moved across the stony beach to the riverside. Then linked together in three’s and four’s they ventured into the torrent. At first the going was easy but by the half-way mark the water was up to the thighs and the current too strong for some bare feet on smooth stones. Nevertheless, in half an hour all were across and only one man dropped his box.

Across the river we embarked upon the long trek up the hillside to Nawalpur. As we toiled on we had a taste of walking in the heat of the day. We six, carrying gaily coloured golf umbrellas, were mainly dressed in cotton shirts, shorts, socks and basket-ball boots. (What a dream those boots are for walking long distances over dry ground.)

Nawalpur proved to be larger than most villages and boasted two or three well stocked shops. We halted for lunch and continued up the long hillside, past a wall of prayer slabs, to a prominent chorten. It was now mid-afternoon and after a short walk beyond, we reached a gompa (temple) flanked by prayer flags. There our caravan rested.

The name of the place was Moolkharka and we had barely pitched camp when we heard a great commotion on the hill behind. Riding down the ridge were two horsemen followed by crowds of people. This strange procession halted at the gompa and began to dance round and round it in increasing frenzy. The dance itself was in the nature of a shuffling gait to the accompaniment of beating tom-toms. The head lama was an old and dignified figure, while the chief dancer wore an enormous hat and was cloaked in a colourful silk garment richly embroidered with designs. Masks were a feature of the display, one man even wore an old army gas mask. The temple was being dedicated, and inside were placed cones of rice and small lighted bowls of oil The ceremony went on unabated long after dark and we were all completely fascinated. On our return to camp we put on a counter-attraction. Fox produced his mouth organ and on a Tamang hillside crowds listened to the lilt of the Skye Boat Song.

Whether or not the gods approved of the evenings’ festivities, we never learned, but evidently they frowned on our own participation, for early next morning it started to rain. Our porters made it clear that they would not carry even in the slightest downpour, so it was after 10 a.m. before we were able to strike camp and get under way. A pleasant path traversed round the wooded hillside to Okhreni. Here was another newly built gompa with a long wall of prayer slabs nearby. These latter with their familiar inscription of ‘Om, mani padme hum,’ also embodied long slate bench seats, affording a good excuse for the coolies to rest. Indeed, a journey in Nepal is measured not in miles, or hours, but as so many ‘resting places.’ A further almost level stretch of path brought us at length to Sanu Gaunda and here, in the early afternoon, we camped. In time and distance it was our worst day.

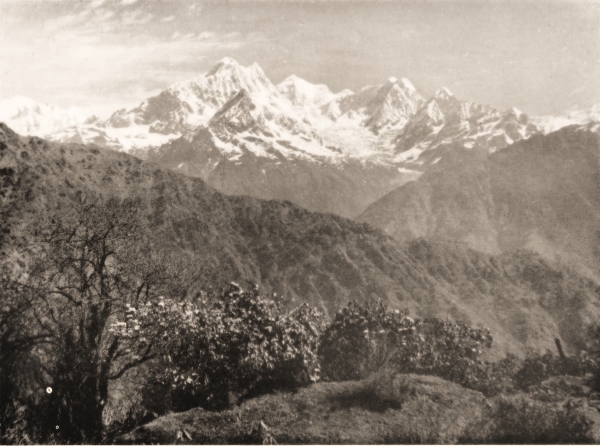

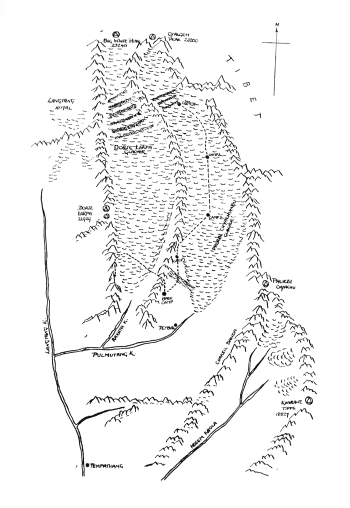

This camp was our highest so far (7,700 ft.) and from it we had a very fine view. Our coolies thought it was good too, good enough to warrant a further advance payment of five rupees each. We gave them some cigarettes and promised the rupees later. The following morning was fine and we quickly whipped up the slopes behind the village to get our first real view of the Himalayan giants. It turned out to be the Gauri Sankar range, so that we were still denied the sight of those we had come so far to see. However, we did not have to wait long. An easy track through the woods emerged on to a broad grassy plateau and there, at last, arrayed ahead of us were the peaks of the Jugal Himal. It was a thrilling moment, and we dallied as we played the game of ‘snakes and ladders’ up imaginary routes on Dorje Lakpa and Phurbi Chyachu.

If the scene ahead was thrilling, that at our feet was hardly less so. Below us at the bottom of a huge valley ran the Bolephi Kola. We had to go down there. It looked an easy path and we reckoned we would do it in an hour, two at the most. It was then 10 a.m. which meant we could comfortably lunch by the river at noon. We padded on and on downhill, and by noon the river seemed no nearer. By 1 p.m. we could pick out a bridge but it was still some distance below. Eventually, we reached the valley at 3.45 p.m. with stomachs empty and tempers frayed. We had received a salutary lesson on the deceptive scale of distances in these mountains, and the irritations of cross country travel. Katmandu is 4,500 ft. yet, after five days trekking, here we were at an altitude of only 3,500 ft. Would we never gain height ?

The porters received their advance payment and made off to the nearby village of Palam Sangu. Before long they returned with the plea that the new five rupee notes were not acceptable j in the village. Apparently, years ago some forgeries of that denomination had been perpetrated and the villagers had never forgotten it. Naturally, we were limited in the amount of change we were carrying and a deadlock seemed inevitable. It was Murari (our Liaison Officer) who hit upon the solution. He suggested that the men be grouped into couples, return their five rupee notes and each pair be handed a 10 rupee note in exchange. To my surprise they did this and accepted the sharing of a large note without demur.

We left Palam Sangu early next morning, the first white men to be seen in the valley. We soon encountered a small girl coming along the path. The sight of Spenceley, Anderson and myself waving our gaudy coloured umbrellas was too much for her and she fled shrieking into the woods. Not even Spenceley’s offer of an empty tobacco tin could placate her. This day too we met Kami Lama, the head man of Okhreni, who was later to be invaluable to us, and he accompanied us up the trail to Gompathang.

By now, we were all famihar with the camp routine. Upon arrival at the site loads were stacked and covered, under Tallon’s supervision. Tents were erected and wood obtained for a fire. Our sherpas then unpacked our kit and laid out in the tents our lilos, sleeping bags, rucksacks and torches. Ang Temba had been appointed Cook and to him would be handed the items comprising the menu for the evening meal. Through all this Jones would hold his surgery and always he attracted plenty of patients. Sometimes they were curable, sometimes incurable. None left without hope.

Beyond Gompathang the track became more truly mountainous in character, dipping down to a tributary and then winding up, with occasional rock scrambles, until we were traversing high above the true left bank of the Bolephi Kola at about 7,800 ft. Hereabouts, we encountered our first sherpa family, a woman and two children living very simply in a bamboo shanty. She was making baskets of bamboo while her husband was away cutting supplies. Pleasantly, the path dropped through the woods to Tempathang, truly described as ‘the gateway to the Jugal Himal,’ and an important stage of our journey was over.

We camped on the outskirts of the village and, as soon as possible, paid off the Katmandu coolies. We had decided to retain Pasang Chittong and take him to Base Camp, so 110 men received 20 rupees each and the two sirdars received 40 rupees each. In addition, each man received five cigarettes, an important part of our currency. We then took on 100 new men and women recruited from Tempathang and the surrounding district. Indeed, we halted a whole day at this point, Tallon and Anderson were very busy that day reorganising the loads, while Spenceley and Jones spent much of it making a photographic survey of the village and its inhabitants. Fox and I discussed the expedition finances. We had left substantial funds at Katmandu for future needs but, even so, were forced to conclude that we must continue to be economical if we were to remain solvent.

It was an undisciplined, happy-go-lucky mob that left Tempathang. Time to them was of no importance. Men and women, old and young, jostled for the lightest loads before a start could be made. With difficulty, Murari listed their names as each passed by. Down we filed to the river which we crossed by a rickety bridge a few feet above the torrent. Quite soon the path entered the jungle which was to engulf us for three days. It was alive with insect life. The going was by no means hard, but these people stopped whenever they felt inclined, and that was often. One fellow imbued with the joy of spring clambered like a monkey up a tall tree and with a few deft strokes of his kukri, lopped off the top. A little more daylight entered the bush. In the early afternoon they made it clear that they had gone far enough for one day and it took Fox some time to persuade them to carry to the top of a knoll, some 500 ft. higher. Yet, it was a lively and friendly crowd that gathered round the camp that night. The tents were festooned with rhododendrons and sherpas danced to the strains of our Leader’s mouth organ.

The going from here on was distinctly rough. The jungle was thick with creepers and bamboo shoots. Tree trunks lay everywhere in crazy fashion. At times ‘ steps’ had to be cut up and over them before progress could be made. Kukris were wielded with much gusto and great skill. At last we reached the banks of the Rakhta Kola. Contrary to expectations, its crossing offered little difficulty. However, once across our porters insisted that this was the place to camp. We were all most annoyed that our progress was being retarded so.

However, next morning (14th April) saw great activity among the porters. They needed no coaxing and in less than two hours we had emerged from the forest to a pleasant pasture known as Pemsall. A halt was made while most groups cooked their tsampa in large bowls over log fires. Hunger satisfied, we trudged on to the slopes beyond. The track, at first gentle, soon steepened and finally became very steep. Even so, the whole party was moving well until the inevitable happened. Accompanied by a great shout comparable to that at the Fall of Jericho, High Altitude Box No. 6 went bounding down the hillside splitting into many pieces and spilling its precious contents as it went. The culprit, a character dressed like Robin Hood, was sent down after it but only half the contents were retrieved. If Robin Hood thought he was going to get off lightly he was mistaken. Ang Temba and Pemba Tensing promptly loaded him with the kitchen box for the rest of the journey. This mishap threw the party out of gear a little and rhythm having been broken the upper slopes seemed harder, until at last we reached Elephant Rock.

It was cold up there, the clouds were down and snow lay all around. It seemed an inhospitable place that day, and a little further on under the lee of a huge boulder, we dropped the loads and took stock of the situation. We stood on one of the few patches of ground within sight. It inclined from the boulder at about the angle of a glacis; it lay at 13,500 ft. and we had to tunnel for water; but we had arrived at Base Camp. Pomba Serebu they called it. We paid off the porters and, as their babbling voices disappeared into the mist, on to an upturned box I flung our remaining cash resources . . . seven annas and a few measly pice.