Ecole Nationale De Ski Et D’Alpinisme Chamonix

by P. A. Bell

For the summer of 1961 I had planned to climb in the Alps with Gunn Clark, but with little money and no particular enthusiasm for any large resort we had more or less abandoned these plans in favour of a holiday in the Calanques, where we would climb over the sea, swim in the sun, and visit all the places of architectural interest.

Asleep at home after a week end’s climbing and sailing at Swanage I was woken by the telephone; it was Gunn to tell me that our Fairy Godmother had appeared. He had been invited to represent the Alpine Club on the international course run by the “Ecole de Ski et d’Alpinisme” at Chamonix. The choice of partner was left to him.

E.N.S.A. is a government sponsored training school in mountaincraft. It is directed by Jean Franco, the famous expedition leader; included on the staff are such well-known guides as Armand Charlet, Andre Contamine and Pierre Julien. Throughout the year it trains porters and guides both in skiing and climbing and the gendarmerie and others in mountain rescue, which is based there. Apart from this, special courses are arranged for such enterprises as the Olympic Ski Team, mountaineering expeditions and, in our case, an international meet.

The course consisted of two people from each of about fifteen countries, ranging from Mexico to Poland, under the general supervision of Pierre Julien. As guests we were completely free to climb when and what we chose in the Massif of Mont Blanc. If we planned to spend time away at huts, food, tickets and hut expenses were all provided. At the School itself we were extremely well fed and films made by French expeditions could be seen for the asking.

In the first few days the weather was bad so we went with Charlet and Julien on to the ice seracs of the Mer de Glace and Bossons Glaciers to be instructed by them. Charlet, whose axes and crampons many of us were using, is perfect on ice, although sixty-five years old. We followed him, at first gingerly, and finally with growing confidence, up very nearly vertical ice without any step cutting. For advice on equipment, routes and conditions we could rely on Julien, a young, vital and amusing man who climbed the Eigerwand with no fuss at all in 1952.

Always we were made to feel that we represented our country and were not just pupils. They asked as much as they taught and we were referred to by nationality, not name. Language difficulties were quite considerable, the Spaniards and the Germans needed interpreters to help them with their French; even so we discussed equipment, routes and mutual friends with great interest and enthusiasm. Some of the equipment produced had to be seen to be believed; the Spaniards had little blade pitons the size of the Y.R.C. badge, with small rings through them; the Italians, fine little expansion bolts; the Americans, karabiners lighter and neater than the latest Allain ones, supposedly withstanding 3,000 lbs. load—to mention only some of the extreme examples.

After a few days the weather brightened and so the more ambitious of us were able to move up to the huts. Gunn and I went to the Torino whence we planned to climb the Grand Capucin by the East Face; Bonatti and Ghigo first climbed it in 1951, taking four days. It was a brilliant piece of route finding, an impressive and almost continuously artificial route of 1,500 ft. With all the pegs in place it has been done in a day, but most people have to bivouac. Due to its steepness and lack of ledges the face is little affected by conditions and, as the guide book says, it is one of the few great routes that will go in a really bad season. In spite of this and the fact that one can abseil down it comparatively easily, it remains a serious expedition, remarkable for continuity of difficulty and exposure. It is graded as “extremement difficile”, but as is pointed out the difficulty is nowhere extreme and all the iron and wood they suggest you carry is unnecessary.

At dawn we were well up the couloir leading to the terraces giving on to the face itself. These easy ledges, being very iced up, presented us with more difficulty than any of the rock, for we were the first to try the route after two weeks of bad weather. Once on the main line of the route the rock was warm and we climbed in sunshine, thrilled by the fine position and character of the climb. By five o’clock we reached the Couzy bivouac where there is actually room for two people to lie down. Being the best bivouac site on the face we were glad to stop. Above us towered the 40 metre wall, leading to the second Bonatti bivouac, a large but steeply sloping snow-covered ledge. This wall was supposed to be the crux of the climb and we preferred not to risk being benighted on it. In fact it went like all the face climbing, more easily than the chimneys, especially when they were ice-filled, in spite of the guide book grading. The night was cold and clear with cloud occasionally drifting up from Italy and over the Vallee Blanche below us. Down in the Plain of Lombardy we could see the haze and flickering summer lightning and just hoped it would stay there.

We waited for the sun since there was no hurry to reach a sun-bathed slushy glacier in the afternoon, and we climbed on in perfect conditions. The climbing continued at exactly the same standard with the same variety of pitches; diedres with awkward overhanging exits; cracks always avoiding apparently inevitable overhangs; short traverses avoiding blank walls; all these on excellent granite with sound pegs and wedges, though the latter naturally were threaded with little better than pyjama cords.

We passed the third Bonatti bivouac site which makes a good stance if nothing else and then heard the first peal of thunder away to the west on Mont Blanc; for seconds it rumbled round the walls of the enclosed Vallee Blanche. By now we were in the cloud which had formed below us and it was hailing slightly. We saw the next flash of lightning and the thunder came from much nearer; then suddenly the rock started to hiss and hum. Before we could possibly have descended any effective distance the next flash came but if anything slightly to the east of us. Like two flies on a wall we were helpless; knowing that a Swiss had been killed by lightning on this route two weeks before was in fact rather consoling, for by the simple laws of chance it was unlikely to happen twice in so short a time. Almost at once the storm had passed us and was grumbling away over by the Géant.

We passed the summit at 6 o’clock and the only incident on the way down was on the first 120 foot abseil from an obvious piton. In the thick cloud I went down and found myself at the end of the rope on a completely blank and extremely steep wall, the north face. By a desperate ‘pendule’ from which I swung back twice I eventually reached a groove and found a peg, though no holds of any sort. I managed to fix myself to the peg and Gunn organised his descent so that the rope passed me in my new position. From the col, which we suddenly saw when the cloud parted for an instant we descended quickly and easily to the glacier below by a series of abseils. We reached the glacier at nightfall, loitered over a meal and made our weary way back to the summit of the Aiguille du Midi on the refrozen glacier. Then we slept on the tables of the teleferique station, going down first thing in the morning.

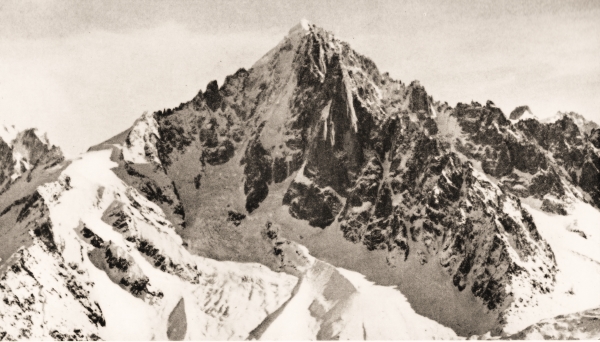

The next route we did was the Nant Blanc direct on the Aiguille Verte; a classic route made in 1936 by Platonov and Armand Charlet. The Poles had done this while we were on the Capucin and everyone seemed to admire it as a great ice route. We set off with one of the Belgians, Jean Bourgeois, at 8 p.m. from Mortenvers and walked slowly up to the Rognon du Dru, where we found two Spaniards encamped preparatory to trying the Pilier Bonatti on the Dru.

At 2 a.m. we crossed the large bergschrund with difficulty and climbed on up the steep ice face above. By dawn we reached the heavily glazed rocks in the centre of the face. We should have bypassed most of these on the right, and wasted time fighting our way through them. By midday we were on the ridge, at the top of which we found hard ice and by four o’clock we reached the summit, not having made good time. The descent by the Whymper couloir could not have been better even if long and uninteresting. Reaching the Couvercle, which was seething with people, we chatted with friends before setting out for Montenvers rather too late. As a result of this stupidity we had to sit out the night on a large boulder in the middle of the Mer de Glace, reaching the breakfast table next morning instead of our beds the night before.

Meanwhile two of the Austrians had started the West Face of the Dru, which they finished in spite of bad weather. After this lapse we set off again for the Rognon du Dru, this time to climb the Pilier Bonatti. We reached the bivouac with food for five days so that if necessary we could wait for the weather.

At the site we found the two Poles and two English friends, Richard Lee and Stuart Crampin, already encamped. They planned to climb the Pilier next day; Lee and one of the Poles had already been up to the base of the couloir and placed a fixed rope over the 50 foot wall so that they could leave at midnight and climb the couloir before dawn.

At midnight, although it was dark, we could not mistake the dark cloud over the Aiguilles Rouges so we waited. After an hour the Poles set off and after two and a half we went too, determined to make a final decision at the top of the couloir before we were committed. By dawn we had very nearly caught up with the Poles and had been joined by two Swiss who had bivouacked further down. The couloir was comparatively free of falling stones though there was no mistaking how they could fall. We were moving quickly together to get out of this infamous place.

Suddenly there was a shout from the Swiss, whom we had left behind putting on their crampons. I looked down to see Crampin and Lee cartwheeling down the icy couloir 1,000 feet into the couloir below. They had fallen from beside the Swiss while passing them in our tracks.

It took time for the four of us to abseil down this 45° to 50° couloir; the Poles round a corner could not see the accident and it was impossible to make them understand due to echo. As we descended we saw a movement and when we reached them we found Crampin alive, though unconscious. Lee had been killed by the fall. One of the Swiss ran down to Montenvers to fetch the rescue party whilst we kept Crampin warm and waited. After six hours from the time of the accident he was taken to hospital by helicopter. The rest of us, including the rescuers, walked down.

Back in Chamonix the weather once again deteriorated and we decided to come home, after an extremely instructive holiday. We made a lot of very good friends, all of different nationalities, whom I look forward to hearing from and to meeting again.