Mountains And Indians In Peru

by H.L. Stembridge

It all started in a corner of the bar at the Old Dungeon Ghyll in Langdale. After a good dinner and a drink or two both Alf Gregory and I were feeling pleasantly mellow and in such circumstances obstacles, however formidable, tend to reduce themselves to manageable proportions. The talk ranged from Persia to Nepal but by bedtime we were committed to Peru. A few days later when I began to read the experiences of other expeditions I found a good deal of it to be decidedly off-putting.

All agreed on the magnificence of the mountains, but — and it was a big but — all talked depressingly of arid, windswept, rather drab uplands, of squalid sullen drunken Indians, of the necessity for a constant guard on trunks or tents against thieves, of the mosquitos of the Santa Valley whose bite produced either death or the dreaded Warts disease which is one stage worse, of the awful penalties of eating Indian food or of going high while insufficiently acclimatised. Moreover, there was no getting away from the fact that I was “getting on”, that Greg was ten years younger and decidedly a “tiger”.

So it was with some misgiving that I met him at Lima Airport around midnight on 21st May, 1963. But one by one my forebodings vanished and the nine vivid weeks we spent together were so crammed with beauty and excitement that even now, six months later, fresh recollections keep bubbling up in my mind to make me smile.

Although our main purpose was to get among the mountains of the Cordillera Blanca, we also wanted to see what the jungle of eastern Peru was like. I find it difficult to describe the peculiar satisfaction of jungle travel. The thrill of shooting rapids in a dug-out canoe after being bogged down for days in a squalid shanty-town, the expectancy of wading up streams hemmed in by impenetrable forest never knowing what may be round the next corner, the flashes of colour, birds, butterflies, flowers, all larger than life, seen against the dark background of the undergrowth.

Nor can I attempt to describe the amusing crudities to which the Turkish-bath atmosphere gradually reduces the interesting characters who choose to live there, men who, despite their primitive surroundings, received us with a warmth of friendship and hospitality that made us wonder which were the more civilised, we or they.

Somehow in Peru, however much you have set your mind on doing certain things, history crops up round every corner and you become as absorbed in the wonders of the past and the people of the present as you do in the mountains you have come to climb. Who are these people whose forebears, 500 or more years ago, built the mighty cities and walls and terraces which still awe us by their permanence and strength? They are the Indians, still the majority in Peru, little changed through the ages, splendid and colourful in a barbaric sort of way, yet as squalid and dirty as we were told. Primitive, down-trodden, unreliable they may be but often hospitable and, on occasion, even gay. All these contradictory attributes enveloped them in an atmosphere which we never ceased to find intriguing and exciting, so if I write as much about people as about mountains, it is simply because I cannot get them out of my mind.

According to Greg the ideal number for an expedition is two or less and it certainly makes for ease of travel. Our plans were of the vaguest, often enough we changed them overnight, and the fact that we enjoyed ourselves so much was largely due to our freedom from organisation. At 4 a.m. on the day after we joined company a single truck left Lima carrying all the baggage and personnel of the Gregory / Stembridge Cordillera Blanca Expedition, for such was our pompous name, just as the tired business men with bloodshot eyes and unsteady gait were returning from the night spots of the city.

Dawn disclosed the Pacific rollers on our left, and on our right, the pitiless sand desert which stretches for two thousand miles down the west coast of South America without a vestige of vegetation except beside the rare stream bed. Occasionally we passed through a village; adobe huts, people in rags,to our yet unaccustomed eyes all rather squalid and repulsive.

After some hours of desert we turned east on a rough and dusty track that followed a stream in to the recesses of the Cordillera Negre, the Black Mountains. Three times we broke down and it was already late in the day before we completed our 14,000 feet of ascent and reached the rolling Puna at the top of the range. Before us was the promised land, as far as the eye could see fairy tale peaks soaring upwards, remote and ethereal—the Cordillera Blanca. Between us and them lay the Santa Valley, perhaps the most fertile in Northern Peru, and here we stayed for five days in a comfortable inn above the Indian town of Huaras. Every day we made forays into the surrounding hills, getting our bodies accustomed to the rarified atmosphere. We bought food and equipment, we engaged two half-breed porters, Donato and Juan, hired six donkeys and, in the evenings, enjoyed the hospitality of members of the Club Andinista Cordillera Blanca.

Towards the end of May we left the little town of Yungay on an old trail that zigzagged up the lower slopes of Huascaran, which at 22,205 ft. is the highest mountain in Peru; our donkeys laden with gear and basic food for three weeks, our two porters happy to be on the move, and Greg and I entranced by the flowers that smothered the landscape. Far from being drab, we had never seen such colour. The sweet scented broom of the valley gave way, as we climbed, to a profusion of blue lupins, bushes covered with yellow and flame flowers overhung the path, passion flowers trailed over the trees while underfoot clumps of giant daisies were surrounded by a carpet of pink gentians. Beyond the gorge of the Yanganuco, at a height of nearly 13,000 feet, we made our first halt by a turquoise lake and while the porters sorted out donkey loads, Greg and I scrambled up the steep hillside to a knoll at over 15,000 feet which gave us a fine view of the unclimbed north east ridge of the north peak of Huascaran.

The next day was typical of the pattern we were to follow in the carefree weeks ahead. A shortish march, often ten miles or less, a camp site by some rushing stream where donkeys could be turned loose to forage for themselves, while we set off to explore some side valley or climb some nearby hill or reach some vantage point from which we could photograph some of the magnificent mountains which surrounded us. Never have I seen such peaks, most of them over 20,000 ft., each standing alone, shapely, beautiful and very intimidating.

All too soon we lost the sun and by six it was quite dark except for the brilliance of the stars. The long cold nights are one of the problems of climbing in the tropics, and down clothing added greatly to our comfort. Sometimes we sat round a roaring fire while the Indians told us tales of the past, or Greg would yarn about Sherpas and Himalaya; more often we would lie in our sleeping bags discussing the problems of a world which seemed very remote. On our journey our camps varied between 13,000 ft. and 15,000 ft. and of course it froze hard at night but with the weather set fair, we always slept with tent flaps wide open and when, at six each morning, the sun rose, as it did with clockwork regularity, the frost evaporated like magic and it was shirt-sleeve weather.

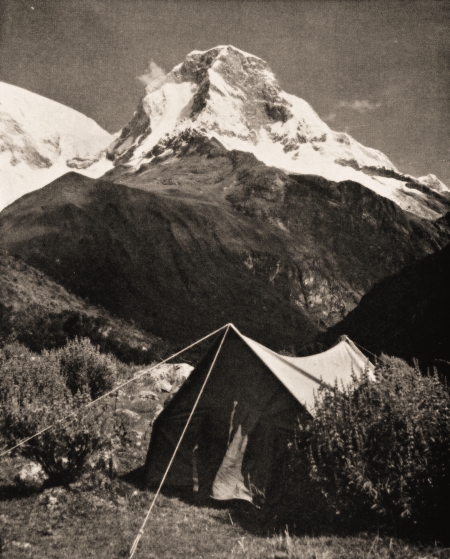

Our highest peak was Nevado Pisco, marked on our maps as “about 6,000 metres” (19,685 ft.); elsewhere I have seen it given as 19,193 ft. But whatever its height it was a wonderful climb, far higher than I had been before and, apart from a great shortage of breath, I was agreeably surprised that I felt none of the sickness or nausea that I had so often read is associated with ascents of high mountains. We managed to get the donkeys up to 14,700 ft., where we put up the bungalow tent as a base with Juan in charge. The same day Greg, Donato and I carried loads up a further 1,500 ft. where we all spent the night by a moraine in the two-man mountain tent. Not a bad night considering the congestion, the only unpleasantness being the ice crystals formed by condensation on the tent walls which fell and saturated our sleeping bags.

Between us and our mountain ran a glacier, large by Peruvian standards and so badly broken up that it took most of the following day to cross, moving slowly and carefully up ice slopes on which great boulders were balanced as precariously as any tipsy tightrope walker. By afternoon we were across and 1,000 ft. above it we found a good site for a second camp below an ice fall at 17,200 ft.

Despite a sleeping pill I had a poor night and felt lousy when we moved off shortly before six. Donato was in the lead and he went too fast for me up a steep moraine and the easy rocks which followed and I was heartily glad when we stopped to put on crampons. But when we took to the snow, with Greg leading at a sensible speed and cutting occasional batches of steps, I found life much more pleasant. Two thousand feet above our heads to our right our peak looked superb, the near vertical rocks of its south face glittering with flutings of ice and overhung by giant cornices fantastically shaped like Swiss rolls. Although the snow line in the Cordillera Blanca in May is as high as 16,000 ft., the deposits above that height are not only enormous but appear to be extremely stable. Snow hangs on incredibly steep slopes and avalanches, at any rate while we were there, were a rarity.

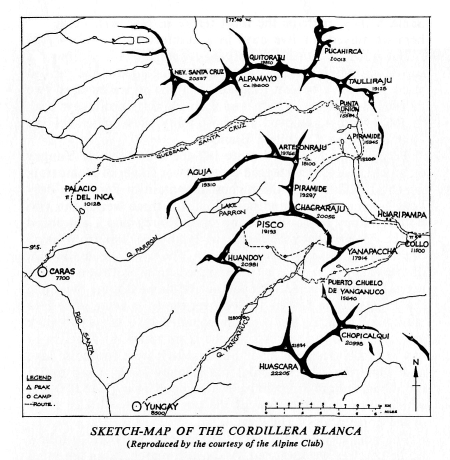

{Reproduced by the courtesy of the Alpine Club}

We headed for a col between Pisco and Huandoy, whose triple peaks, the highest reaching 20,981 ft., lay well over to our left, looking far from easy. A good deal of step cutting became necessary as the angle steepened above the col. Then followed a crevassed area below groups of seracs before we reached the long slope that led to the summit. This caused us the only headache of the day for the sun had softened the crust and we kept going through knee-deep. Hard work at 19,000 ft. that made us gasp for breath, so much so that Greg, who was breaking the trail with his tongue hanging out, swore he had it sunburnt.

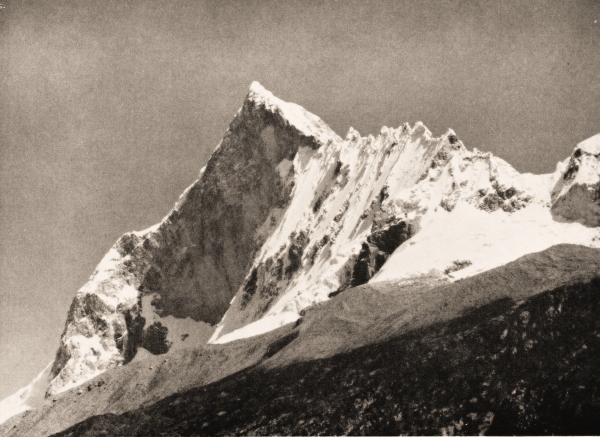

But such details were forgotten when we reached the top and gazed in wonder at the incredible west ridges of Chacra-raju, not far away and seemingly unclimbable. Below us lay the Parron gorge with the shapely cone of Artesonraju at its head. Away to the north the great peaks beyond Quebrada Santa Cruz, Taulliraju, Alpamayo and Nevada Santa Cruz formed the skyline.

We had no time to linger if we were to be down by nightfall. Juan came up to the top camp and, with his help, we carried the lot down to base, although the glacier caused us even more trouble going down than it did coming up and I, for one, had had enough by the time I staggered into camp in the darkness.

During the off day that followed several condors soared overhead. Their eleven-foot wing span makes them the greatest eagles on earth and they certainly dwarfed the vultures which were a permanent feature of the skyscape. Among the bushes of the valley humming-birds flashed like jewels as, with vibrating wings, they sipped nectar from the flowers. Tiny hawks, no bigger than thrushes, hovered nearby and wherever we turned myriads of strange birds of all sizes and colours piqued our curiosity for we had no means of identifying them. Here too were remains of old terracing and huts, although the valley was no longer inhabited, and all these had to be investigated. So with one thing and another it was dark all too soon.

Shortly after sunrise we headed down the valley until we could cut over a shoulder, itself a flowery paradise, and join the track that climbed to the Puerto Chuelo de Yanganuco Pass which, at 15,640 ft., crosses the main watershed of South America. As we reached the crest it was a sobering thought that, beyond the blue foothills ahead, over two thousand miles of tropical forest, almost uninhabited and largely unexplored, lay between us and the Atlantic. Beside a little tarn, not far down the eastern slope, we camped among the lupins and watched the last rays of the sun redden the snows of Chapicalqui, which looked all of its 20,998 ft.

It was a lovely walk next day, dropping into a valley that grew more fertile with every mile so that, by the time we reached the handful of thatched huts known as Colcabamba, the stream-side vegetation seemed truly tropical. Here we camped on a little knoll beside a field of ripening maize while, for three days, we explored the district, making friends with our neighbours who, poor as church mice though they seemed, were hospitable and friendly. From the fresh maize stalks they were brewing chicha, the maize beer, copious quantities of which are consumed at all Indian gatherings, and everybody we met was chewing the young stalks which were as sweet as sugar cane.

A conical hill rose a few hundred feet above our tents and here too was ample evidence of an ancient community. Scattered among the ruins, half covered by soil and undergrowth, were great blocks of granite, a yard square and a foot thick, on which carvings of animals or geometric designs stood out in relief almost as clearly as when they were sculptured over 2,000 years ago. We dug them out, made sketches and, weeks later at Lima, were tickled to be told that, although the site was recorded, the carvings were unknown. Tales of half-buried cities to the east intrigued us and we began to fancy ourselves as archaeologists!

But our journey took us north up the valley of the Huari-pampa to where a side valley joins it from the west. Here we stopped to climb a hill of 16,000 ft. marked on our map as Pyramide, from whose steep slopes the ridges and pinnacles of the east face of Chacraraju fairly took our breath away. Here too we climbed to a lake high above our tents. It was one of those days when, with no great intentions, we kept pushing just that bit higher to see what lay beyond the next ridge. Greg and Donato were going as fast as they would at sea level. I was slower and, at around 17,000 ft., dropped out while they pushed on to climb, on the spur of the moment, a virgin peak of over 18,000 ft., which sprang from the ridge running north from Chacraraju. We followed the Huaripampa Valley until it petered out below the glaciers of Taulliraju. For hours we traversed below the precipices of its unclimbed south face, but try as we would, we could discern no possibility of a route up the 5,000 ft. of rock and ice that led to its summit.

For the first time the weather looked unsettled, heavy cloud blowing up from the east kept hiding the tops, and we were in some doubt whether to camp where we were or to put a high camp on a ridge to the east with the object of trying for a peak the following day, or to push westwards over the Punta Union Pass. The donkeys were far from fresh but against that there was little bite for them on this side of the pass and we had enough hours of daylight left in which to get over the watershed. Moreover, it was obviously snowing higher up and the prospects of getting a peak were uncertain, so we settled for the pass. But this certainly looked no cakewalk. Ahead lay a series of slabs leading up to an imposing rock ridge nearly 16,000 ft. high which was apparently sheer for the last few hundred feet. It looked impossible to get fresh donkeys over it, much less tired ones, heavily laden into the bargain.

But it wasn’t! They climbed like goats and when we reached the top pitch which was indeed almost sheer, we had one of those surprises that make mountain travel in Peru so exciting and so different from anywhere else in the world. For there, zigzagging up the rock face, was a ramp, probably made in Inca times or earlier, and just wide enough for a laden donkey, which led us to a narrow cleft in the knife edge crest of the ridge. Once more we stood on the main divide of the continent, gazing westwards this time to the Pacific.

The far side was nothing like so steep and we dropped as quickly as the tired donkeys could travel until, by a stream bordered by lupins, we found a good site for the tents with plenty of herbage. We were on the fringe of a shallow combe, a mile or two across, that marked the beginning of the Quebrada Santa Cruz which, for twenty miles or so, runs westwards to join the Santa Valley. The glaciers of Artesonraju seemed close above our camp, the great pyramids of the Alpa-mayos, though not far away, were hidden in a combe of their own and, to the north, the many summits of the Pucarhirca massif looked confused against the proud single spire of Taulliraju.

All next day we stayed there probing this side valley and that, scrambling to any vantage point that would enable us to see just one more aspect of these superb mountains. I remember too that we contributed our quota to the spread of European culture by teaching our boys to play “boule” with rounded stones.

Next day’s march was a fairly long one. To find grazing for the donkeys it was essential to get beyond the gorges of the Quedraba Santa Cruz. For the first few miles we kept dropping from one flat area to another, searching for places to cross a deep stream that meandered through marshy ground. The place was alive with birds, flocks of pied plovers, many waders and innumerable wild geese among the spongy tussocks that indicated the approach to a large lake. Here the flats ended and we had to clamber up the rocky hillside to dodge the cliffs that margined the shores.

Beyond the lake a few wild looking cattle were being rounded up by a trio of equally wild looking men riding bareback. As they rode up to greet us we noticed that one carried a rifle and he explained that they had been out hunting for venados, the wild deer of the Andes. A rough track led past their thatched huts and, a few miles beyond, descended by a series of steep zigzags into the gorge. Our donkeys kicked up clouds of the dust that covered the track inches deep and, hemmed in as we were by the narrow walls and tropical vegetation of the gorge, the air felt heavy after weeks among the heights. The eye wandered perpetually up the steep rocks to where the snows of Nevado Santa Cruz shone 10,000 feet above our heads. The rough stony track, the dust and the confined space made for heavy going and I was glad when, after what seemed an interminable time, we could see the end. Here the gorge was so narrow that a heavy door in a rock face sufficed to block it, though whether its purpose was to keep marauders out or to keep cattle from straying, I couldn’t make out.

Once beyond the door we were in a different world, a pastoral world of small red-roofed farms, each surrounded by a few cultivated fields and shaded by clumps of eucalyptus trees among which parakeets chattered. The maize was being harvested and we camped in a tiny patch of stubble where the donkeys ate their fill of the sweet green stalks, while we enjoyed freshly boiled cobs for supper.

We spent most of the following day climbing steadily in an endeavour to find a place marked on our map as “El Palacio del Inca”. Repeated enquiries produced the vaguest of answers and it was late in the afternoon before we climbed a little hill and saw below us the great quadrangle, a hundred yards square, that must be the “palace”. It was, in fact, one of the great storehouses built by the Incas and stocked with food and other necessaries at strategic points throughout their domains. Our little hill must also have been populous in ancient times for it was covered with the ruins of great walls and riddled with underground passages. Connecting it with an adjacent hill was an escarpment that dropped steeply to the Santa Valley 3,000 or more feet below, and along its edge the remains of a string of fortifications were now occupied only by scorpions and tarantulas.

For some reason the details of that evening stick in my mind, perhaps it was the peace of the place, but I can remember all the changing colours of the sky as the sun sank behind the Cordillera Negre; orange, red, lilac, then violet before merging into the navy blue of night. We were now torn between a desire to go on wandering through these gentle uplands and the more worldly attractions of the little Indian towns of the Santa Valley. In the end the valley won and we were not sorry for, while our boys drove the donkeys up the forty odd miles of dusty track from Caras to Huaras, Greg and I reached Yungay on the eve of the Corpus Christi celebrations.

If only I could describe the rapture of the crowds as the Host is borne through the streets, the chanting, the spreading of flowers, the thousands of lighted candles and the fervour of the kneeling multitudes. Or even attempt to convey a fraction of the excitement that mounts during the fiesta that follows when one and all, whether dressed in their brightest and best or only in rags, take part in the boisterous tomfoolery that makes them roar with laughter. The mummers, the musicians, the jesters with their practical jokes at the expense of all and sundry, the drinking, the roasting of pigs in the streets; this must be the way in which our own festivals were celebrated in mediaeval times, long before Christmas became a commercial proposition.

That the Indians of Peru are, in the main, ignorant, poverty stricken and without hope is obvious, but to condemn them as sullen, drunken and unreliable is wrong; so should we be in their environment. What really is remarkable is that, after being downtrodden for centuries, they still retain that spark of gaiety which, given the chance, enables them to enjoy a bit of spontaneous fun just as much as the rest of us.