The British Expedition To The Edelweisserhuttenschacht, 1965

Part I: The Edelweisserhüttenschacht

by D. M. Judson

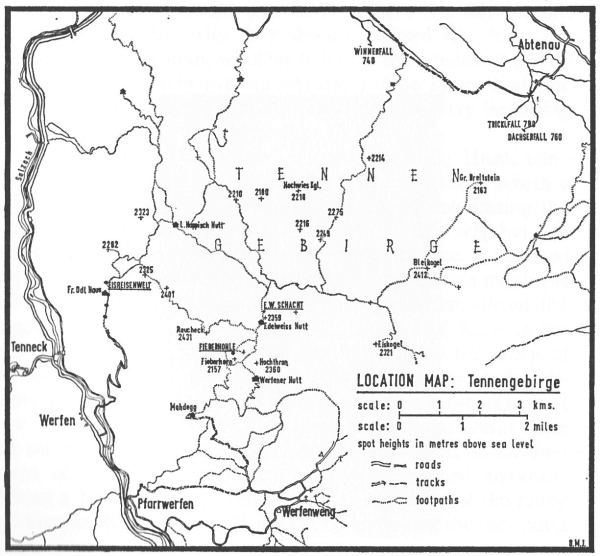

The Edelweisserhuttenschacht is a pothole in the Tennenge-birge massif of central Austria, 25 miles south of Salzburg. It is situated at about 7,500 ft. on the summit ridge of the Streitmandl, 200 yards north of the hut of the Edelweiss Climbing Club, the Edelweisshutte. Four holes unite a short way down to form one 300ft. entrance shaft.

The area is a typical karst plateau of gently folded rocks of upper (Alpine) Triassic age. The Dachstein limestone exposed on the plateau gives way to a Dolomite limestone at some depth, which does not seem to be amenable to cave formation, as is evidenced in the Eisriesenwelt. The whole dips gently to the north east. The only large scale risings for the Tennengebirge area appear about four miles to the north east of the shaft at an altitude of 2,350 ft.; these are the Winnerfall, Tricklfall and Dachserfall, near Abtenau.

Two British expeditions had previously been in the area, in 1963 and 1964, and had put in the initial ground work. The 1964 expedition, in which John Middleton took part, had descended the entrance shaft and carried on down another four pitches until turned back on the brink of a deep shaft at a depth of about 550 ft. On both these occasions the Edelweisshutte was used as a base camp and an Austrian Government helicopter was used to ferry equipment up from the road vehicles at Werfenweng.

Our objective in 1965 was to put the strongest possible teams down the shaft in order to pursue it to its ultimate depth. We were prepared to go down beyond 3,000 ft. and to make prolonged camping trips underground. The final size of the party was twelve, although sixteen had been the planned figure: D. M. Judson, Leader; J. R. Middleton, Secretary; B. H. Twist, Treasurer and Communications; M. Clarke, Surveyor; J. Gregory, Food Officer; O. Clarke; R. Dalton; G. Edwards; A. Gamble; J. Garrity; J. Higgs and M. Wooding. So as to obtain the most efficient use of our manpower it was planned to use small assault parties spending the minimum time below ground and coming out for short rest and recovery periods; in fact a ‘hit and run’ policy. If necessary two- or four-man camps would be set up. The laying of a telephone line would closely follow up exploration at all stages to provide rapid reporting back of information and rapid follow-up of parties.

Our problems, we thought, would be threefold: to move about half a ton of equipment and food from the valley up to the hut about 4,000 feet above: to equip a 300 ft. entrance shaft so as to make the passing up and down of men and gear reasonably easy: to make the best use of our manpower by means of underground communications in the exploration of the totally unknown. Given good weather our first problem was solved with the loan of a helicopter from the Federal Ministry of the Interior of the Austrian Government.

In order to improve working conditions on the entrance shaft it was decided to divide the pitch into two sections of about 100 ft. and 200 ft. each, by the erection of a scaffold platform at the most constricted point in the shaft. It was also proposed to ladder the first 100 ft. section from the opposite end to that which had been used by the previous expeditions so as to reduce the free, or overhanging, sections.

The men and equipment met at Dover on Saturday, 7th August, for the 3 a.m. boat to Ostend. Transport consisted of a long wheel-base Land Rover and trailer, a 6 cwt. Bedford van and a Volkswagen car. We drove continuously through Saturday and met again at a camp site near Golling, 15 miles south of Salzburg.

Sunday dawned a perfect day; M. Clarke, Middleton and Judson made an early start for Salzburg to arrange the helicopter. The equipment went to Werfenweng to await the airlift and Gregory got the first party off to the Edelweisshiitte. Everything was going perfectly; the helicopter arrived at Werfenweng just before midday. Unfortunately, when he got up to the Edelweisshutte, the pilot was unable to bring the machine down. The thermals rising up the steep face of the mountain lifted and buffeted the ‘chopper’ to such an extent that it was impossible for it to make a safe landing. Seven attempts were made, but it had to be called off until the evening. We waited at Werfenweng until 15.00 hours when we learned that the chopper had been called to a rescue on the Dachstein. The attempt was postponed until 7 a.m. next day.

M. Clarke agreed to remain at Werfenweng to load the chopper next morning, while the rest of us packed as much kit as we could carry and drove to Mahdegg to start the long haul up to the Edelweisshutte. It was 5.30 p.m. by the time we left Mahdegg, a very late hour indeed, but we were eager to reach our new headquarters on the mountain and we did have John Middleton with us, who knew every inch of the way. At the end of the long slog to’ the tree line we called in for a refresher at the Werfener Hutte. From there a traverse around the foot of the Hochtron brought us on to the vertical steel ladder and the long steep scree slope between the Hochtron and the Fieberhorn. By this time it was rapidly getting dark and before we could reach the snow at the top of the screes it had become pitch black. At this stage John was not quite so sure about the route, there was talk of ‘much more snow than last year’ and of 3,000 ft. faces somewhere ahead. We had only one choice: to bivouac.

As the clouds thinned out a little after daybreak we gradually became aware of our position and found that we were no more than 20 minutes away from the Edelweisshutte. The hut is superbly sited within 5 yards of the summit of the Streit-mandl and 200 yards from the shaft. Some of us went for our first look at the “Grosse Schacht” and took stock of our new surroundings, others chose to get in more sleep.

Throughout Monday the sea of cloud between us and the valley never parted, no chance of seeing the helicopter; clearly this situation could last for a long time. We decided to bring up food and the vital kit for rigging the entrance by the hard way, as much as we could carry each day until the chopper came. This was probably not a bad thing, it improved our physical fitness; unfortunately we were losing valuable time. The tedious process of ‘gardening’ the shaft was begun, there were many small ledges in the first 100 ft. We cleared all these of rock and glass as best we could and settled on a site for the platform at about 95 ft. down. It was not quite as we had expected from the 1964 survey. The very narrowest part at 105 ft. was too tight for our purpose and possessed no useable ledge, in fact below this level the shaft immediately belled out to its widest part, about 30 ft. by 30 ft. We returned 10 ft. from the narrowest point to where there was a good triangular ledge about 18 inches deep. We had our site but, as yet, no more than 150 ft. of ladder and no platform kit on the mountain.

Tuesday was still not helicopter weather. All members descended to the valley for a major carrying assault, leaving the hut at 9.15 a.m. and taking only 1 hour to reach Mahdegg and the vehicles. By evening we had brought up all the equipment for the platform: scaffold poles, shackles, connectors, rawl bolts, T. & G. boards, spanners and a saw, and enough ladder, but not rope, to tackle all the known pitches with 50 ft. to spare.

Wednesday remained cloudy, still not helicopter weather. M. Clarke and Twist set out with another carrying party for the valley. Wooding and Judson descended to the 95 ft. level and started the construction of the platform. Two and a half hours were taken to cut and erect the main four-member frame.

They returned after lunch to fix the T. & G. boards; as more boards were put in the upward draught became a howling gale. The task was a most unpleasant one with, at the outset, only a couple of small ledges to stand on, a drop of 200 ft. below, almost freezing rock and an icy blast coming up from the depths. On top of all this, all the drips in the shaft seemed to have been specially designed so as to drop straight down the necks of the workers.

At 6.30 p.m. the platform was deemed to be complete, with the final 200 ft. of ladder hanging temporarily from one of the main scaffold members. Garrity joined us on the platform and then continued through to the bottom, clearing on his way the small ledge 200 ft. down. The tackle was lowered and we joined him. We were standing in a large chamber; the roof came down at 45 degrees and the floor sloped away to a boulder fall at the farthest corner.

The three of us set off from the bottom of the shaft with 400 ft. of ladder and several long ropes, across the chamber and down the two short pitches, 10 ft. and 20 ft. The chamber at the bottom of the third pitch was circular and about 20 ft. across; a very small hole at floor level, almost closed off with debris, was the start of 200 ft. of protracted agony; a twisting and steeply descending crawl in a keyhole shaped passage. The gap in the floor was almost continuous to the head of the fourth pitch, in places up to 50 ft. deep and just large enough to admit the passage of a tackle bag. We battled on like a small party of ants, passing on the tackle bags in relays of ten feet or so at a time, until we eventually reached the head of the 130 ft. pitch. We put a ladder down the pitch and then thankfully turned for out; back to the hut for a very late dinner. Whilst we had been below, Higgs had kept a lonely vigil at the platform and had completed the three rawl-bolt fixings for the ladder and 450 ft. double life-line.

For the five of us in the hut Thursday dawned in a most abrupt manner. We were suddenly awakened from our dreams of deep shafts and large mounds of tackle by a strange sound; it became louder and louder. Yes, the chopper had arrived. Within seconds we were all running about half dressed and in a daze; boxes, drums, barrels and tackle bags were feverishly ferried towards the hut. Four loads and all our remaining food and equipment had arrived on the mountain; it had to be sorted and stacked in and around the hut.

Friday saw the first major assault party launched; Middle-ton, Higgs, Wooding, Edwards and Dalton. They left the hut at 9 a.m. taking a tackle bag each, 350 ft. of rope and a certain amount of concentrated food. Meanwhile on the surface preparations were made to fix the heavy duty telephone line down the entrance shaft. The line was slowly lowered and fastened back through the pitons, thus holding it away from the ladder. Eventually the whole of the 400 ft. of line was in position, anchored at the top with its own stainless steel reinforcement to a rock bridge and fastened back to the wall at the bottom. In the Main Chamber we met the returning assault party; they had a sad story to relate.

The great 200—400 ft. shaft which had halted the 1964 exploration appeared not to exist any longer! In its place was a mere 60 ft. pitch finishing at the foot of an enormous unstable boulder fall. Prospects were not good.

On Saturday the second assault party was launched: Judson, M. Clarke, O. Clarke and Garrity. Our object was to investigate further the possibility of by-passing or traversing round the terminal boulder fall. Gregory, Twist and Gamble followed close behind laying the telephone line through the crawl and photographing. Progress was rapid, all but M. Clarke abseiling the entrance pitch. We carried only light food bags, pitons and belays.

The first 50 ft. of the fourth pitch turned out to be considerably narrower than had been expected; at the 50 ft. level it opened out into a large boulder chamber, 30 ft. by 60 ft., slightly offset from the line of the ladder, and below this it continued as a 6 to 10 ft. wide rift. The small amount of water first seen at the head of the fourth pitch disappeared in debris against the back wall of this long narrow chamber at the foot of the pitch. At the other end of the chamber a narrow, winding, floor-less rift continued. This had been laddered, the fifth pitch, it was 50 ft. deep, ending in a small chamber. Here the stream was again seen, but disappeared in debris as before. Another descending rift followed, it had a small winding cleft in its floor, this, after about 50 ft., became just wide enough to admit a man. This was the head of the final 60 ft. pitch; it looked wet and large boulders could clearly be seen below. Beyond the hole, the floor of the rift climbed some 10 feet or more to where a large crumpled boulder was resting diagonally across the passage. The space left above and below this boulder formed two large windows which gave an excellent view of a cavern whose floor was some 50 ft. below. The whole cavern was a tottering mass of boulders and debris; this balcony position gave the most fearsome insight into the power and devastation of nature that any of us had ever witnessed beneath the earth.

We re-hung the ladder down the hole in the floor of the rift, once through this small hole it was hanging centrally in a shaft six to ten feet wide. A steady flow of icy water poured down the ladder from a small hole just below the take-off point; its bottom was in boulders, generally about two feet across. Climbing down about ten feet from the foot of the ladder the lowest point was reached. Another little stream flowed down the end wall and was immediately lost in the boulders. Looking back behind the ladder, a wall of boulders rose almost vertically to a height of about 100 ft., loosely jambed between the smooth walls of the shaft. All this was resting on a mass of very small material, whilst near the top were rocks the size of cars. Any attempt to climb up this slope was unthinkable; to breathe was a hazardous exercise.

We could only conclude that at some time during the previous twelve months an enormous cavern collapse must have taken place, filling in or sealing off the ‘big pitch’ of 1964 fame. We had got 60 ft deeper than the 1964 expedition and had met an absolute barrier to our exploration. We retired taking the tackle from the bottom three pitches with us.

Sunday and Monday were spent in removing the tackle from the pot and in pondering over our next move. We had planned, in this event, to visit some of the nearby shafts pinpointed by previous expeditions, but this year most of these were covered with snow. Some of us decided to visit the risings near Abtenau and see for ourselves where the water went to.

These risings were found to be most impressive, although obviously not in spate. The most northerly, the Winnerfall, is the largest; when in spate it must form a 500 ft. cataract down the side of the mountain. At the time of our visit it was completely dry, but at its top a solution passage dipped steeply into the mountain, this finished after 100 feet in a deep siphon pool. Water was rising over a considerable length of stream bed several hundreds of feet below. In total this added up to a very large resurgence, though clearly only a small fraction of what it must be at other times of the year.

On the Wednesday we visited the Tricklfall and Dachserfall. The latter is something of a tourist attraction, with water spouting out of several small holes under pressure, whilst the former seemed to be a flood rising. During our trip around the valleys we made contact with Dr. Oedl, who very kindly agreed to arrange for us a trip into the further reaches of the Eisriesenwelt on the following Saturday.

By the Thursday evening we were all back at the Edelweisshutte with the exception of Middleton and Higgs who had gone off to look at caves on the Eiskogel. As the weather conditions were good we decided to call the helicopter for the Friday morning and then after our visit to the Eisriesenwelt, to continue operations from a low level camp at the end of the track at Mahdegg. Everything went smoothly on Friday; the chopper arrived at exactly 8 a.m. and most of us were up at 6 a.m. to pack the food and kit into handleable units for the lift. All was sorted out at Werfenweng and we met Dr. Oedl in Werfen at 7 p.m. He escorted us up the steep track to the end of the mini-bus route, and we were soon up the cable-car, eating and drinking in the Oedl-Haus, where we were to stay the night.

Part II: The Eisriesenwelt

by D. M. Judson

We awoke to discover our superb situation, in the loft of a large hut, on a fertile ledge about 3,300 ft. above the Salzach Valley. An 8 a.m. start was made into the cave, giving us an hour to take photographs of the ice section before the first tourist party would be upon us.

From the shelter of the large entrance portal, with its magnificent view across the Salzach valley to the Hagensge-birge and beyond, we moved off down a funnel-like passage to the entrance door. When our guide opened the door, the outward rush of air was terrific. The going was easy at first, but once through the large Posselthalle we came to the foot of the Great Ice Wall; here a steep slope of ice spans the passage from wall to wall. As we ascended the wooden stairs, I thought of the original explorer, von Mork, and his colleagues in 1913, laboriously cutting steps upwards into the unknown.

Above the Ice Wall the scenery is composed almost entirely of ice; our guide kept dodging behind ice curtains and into Tee Chapels’ where he would light magnesium flares from his carbide hand-lamp. The cold green light from the translucent ice would expose the striations representing the annual recession and development of the ice. Out of the party of eight we had four photographers; they were now working flat out. Round every corner was a scene more beautiful, more spectacular than the last. Our guide was burning magnesium ribbon here, there and everywhere, bulbs were going off, shutters were clicking; this was truly a photographers’ paradise.

At one point a deviation was made from the tourist route, at first through a very low section with ice floor and small ice-columns into a series of boulder-strewn chambers and eventually into a final one, the Cavern of the Ice-Men. In the centre of this large cavern was a forest of ice stalagmites, some of them up to ten feet high, and made of the clearest translucent ice. Being mid-August, they were of course in decline and we were told that in the spring they would be even more superb, some of them up to 20 ft. high.

We returned to the tourist route where another great ice barrier was reached; in places it was solid right up to the roof and the path traversed an excavated channel. We descended a flight of wooden steps and entered a long gallery. The left wall was of sheer ice, banded every foot or so with annual recession lines. The roof gradually became higher until we found ourselves in the centre of the great ‘Mork Hall’. Here in an urn, in a niche at the far end of the Hall, are the ashes of Alexander von Mork. We passed on through several smaller passages, down through the ‘U-tube’ beyond the tourist section of the cave, and beyond the point reached by J. W. Puttrell in his tour of 1932 (Y.R.C.J. Vol. VI., No. 20, p. 122). At the low point of the U-tunnel what is now a small area of ice had once been a large lake; this used to be traversed with the aid of a steel suspension device, of which the remnants could be seen in the roof. Somehow the pool had mysteriously disappeared.

We had by now left almost all the ice behind us and were progressing slowly up the long gradual climb of the ‘Midgard’. Here a tremendous amount of work had been done between the wars breaking up boulders and levelling the floor, preparatory to building a railway. A few individuals had had an ambitious plan to build a railway right through the length of the Midgard to take tourists through almost to the ‘Oedl-Dom’, where a natural shaft would have been cleared out and a lift would have been put through to the surface, about 1,000 ft. above, thus making a round trip. After the last war the plan was never revived and now only the cleared causeway remains.

We followed the northernmost wing of the system through the ‘Fritjof Oedl-Dom’ until we reached the final boulder fall of the ‘Dom des Grauens’, a great rambling unstable mass of boulders. The Oedl Dom is one of the largest in the system, probably twice the height of Gaping Gill, but lacking any sort of character, with only a small trickle of water from the roof. We returned from this section and were taken up a long and dangerous boulder slope into the Trrgarten’. Our guide had not been in this section before and was most concerned that he might lose some of us in this maze-like region. We turned back at the start of the ‘Great Canyon’ having seen only a small fraction of the 30 miles or more of the explored cave system.

We had been allowed to wander as we pleased through what is possibly the finest ice cave in Europe and we had seen a little of the sombre galleries that lie beyond. It had been an eight hour trip and quite a strenuous one. Somehow during the evening we all became involved in a rather gay party in the Oedl-Haus, some a little more involved than others!

Sunday was very much ‘the day after’; we packed our bags, descended the cable-car and headed back to Mahdegg. Most of the kit was picked up from Werfenweng, packed into the trailer and carted up to Mahdegg where our new base camp was set up. A hole, later to be known as the Fieberhohle, had been reported by a member of the Edelweiss Club, its entrance was about 1,000 ft. above Mahdegg. From preliminary inspection its potential seemed good and we decided to concentrate the rest of our efforts upon it.

Part III: The Fieberhöhle

by J. R. Middleton

With the exploration of the Edelweisserhuttenschacht finishing in less than a week, we had to search the surrounding mountains for fresh possibilities. Many promising holes which we had noted during the hot summer of 1964 were, in 1965, found to be covered with ten to fifteen feet of snow. We visited the Ebental without success, then went on to the Hochweiss where we discovered several small ice caves and shafts descending fifty to a hundred feet to choked bottoms, but nothing of any significance. Morale had in fact reached rather a low ebb when a member of the Salzburg Edelweiss Club told us of a hole which one of their members had descended for about 100 ft. and which still went on. This was known as the ‘Fieber-höhle’.

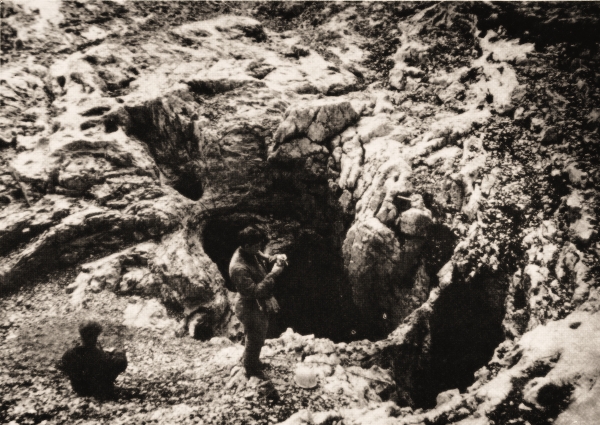

The Fieberhöhle is situated on the western base of the Fieberhorn, at an altitude of 1,875 metres, only one and a half hours’ climb from our new base at Mahdegg. The hole itself is in a steep, smooth and water-worn rock slope, so that when it rains, as it often did in 1965, the water rushes down the slope into and over the entrance, completely blocking it. During normal weather the hole is quite dry.

The assault was made in three stages: on the Sunday following our disappointing finish at the Edelweisserhuttenschacht, Wooding took a party on a preliminary exploration and reported great shafts and fine pitches; on the Monday Judson, Middleton and Gamble penetrated to halfway down the last pitch, followed by M. Clarke, Twist and Higgs surveying; on the Tuesday Wooding, Edwards, Dalton and Garrity reached the bottom at 722 ft. below the entrance.

The start is large enough but only just, to allow an average man through comfortably. Several pitons had already been placed by the Austrians as belays for the ladders on the first pitch, the top 20 ft. of which is vertical and free-hanging on to a large rock-strewn ledge (A). The next 50 ft. goes down a 60 degree slope made up of delicately poised boulders which peeled off, roaring and rattling their way to the bottom of the pitch as each man passed over them; added to this the ladder persisted in attaching itself near the bottom, making it a 45 degree climb inclined in two planes. A truly horrifying section and one which only dire necessity would get me past again. The final 40 ft. of the first pitch is down a clean washed wall finishing as expected, in a boulder strewn chamber.

A narrow fissure leads off, one enters this horizontally and feet first, it continues for 10 ft. to* a 90 degree bend where one drops immediately into a small chamber (B). Here it was very cold, there was a draught strong enough in the fissure to blow out our carbide lamps. The route goes on round a corner, through a tight squeeze, along a short passage to a second tight squeeze and so to1 the top of the second pitch (C). The drop at (C) is only 15 feet and finishes on a sloping ledge with a 20 ft. choked pitch below it. The way on is by traversing round to the left, climbing upwards, round the top of a pitch of unknown depth but met with again lower down, and over a large flake of rock. At the end of a short passage is a pitch (D), of 70 ft. with two good ledges. In fact from this point downwards is just a long series of pitches, from one rock bridge to another, all part of a large and very deep rift-like shaft.

From the bottom of pitch (D) a high and fairly wide section leads to a 10 ft. climb (E) on to a large ledge at the top of the next ladder descent of 30 feet. At the bottom of this is a much smaller rock bridge (F), four feet wide between two walls, just about big enough for 3 men; at one end is a pitch of about 230 ft. and at the other is one of 85 ft., which is the one we took. The ladder lands one on what seems to be a boulder-choked continuation of the shaft (G), the main route goes on through a high fissure. An interesting inlet passage comes in at this point but we only explored it for about 100 feet to a 15 foot drop.

As might be expected in this pot where one vertical drop succeeds another, through the fissure there is a shaft, this time only of 45 ft., which takes one into the 230 ft. pot mentioned above and to finish this off is another pitch of 75 ft. where, after an awkward start, the ladder hangs free to a boulder strewn floor at (H). These boulders were generally very unstable and even though 15 or 20 feet high were quite likely to move several feet if touched. In several places stones dropped down between the boulders fell a considerable distance.

By climbing up the side of a boulder the size of a house (I), the next pitch, of 20 ft., is reached. This has a tight and difficult take-off and lands one on a two foot wide rock covered sloping ledge ‘(J), on the edge of a 50 ft. drop. The way on is to traverse round this on to solid ground and up a rather tricky 30 ft. climb to a ledge (K). Again this is smothered in medium sized rocks, many of which we had to tip down the next and final pitch with a grandly reverberating roar. Two holes go down from this point, one drops sheer for 120 ft. to the bottom (L), the other is in a corner and goes down via a ledge. From this, yet another boulder strewn floor, there seemed to be no feasible way onwards, certainly not without some very vigorous digging. So at a point 722 feet below the entrance the party met with the same kind of disappointing finish as in the Edelweisserhuttenschacht.

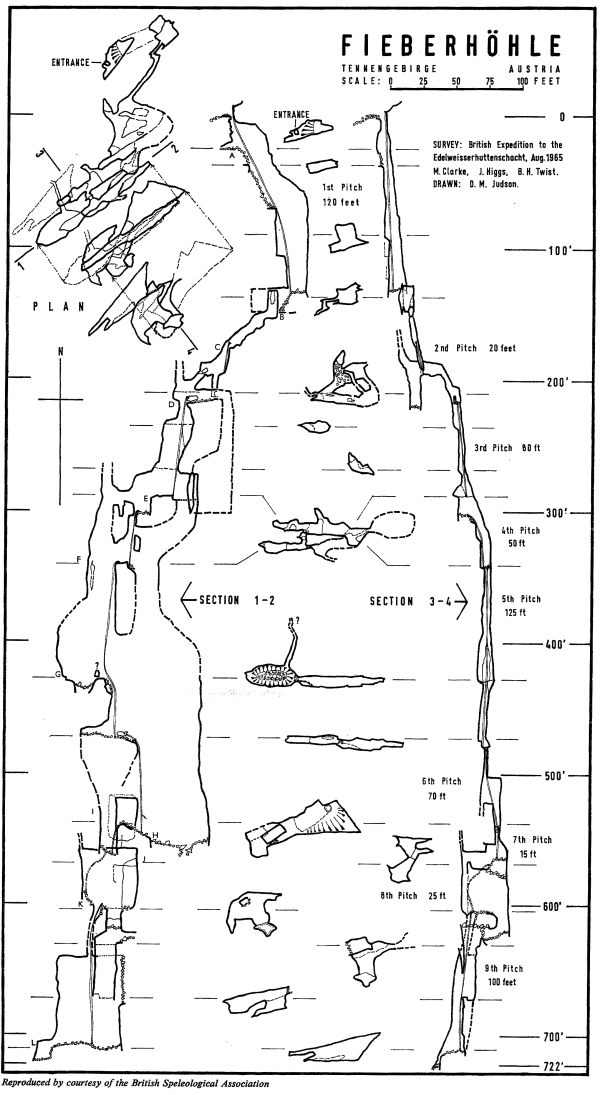

The Fieberhohle is in the truest sense of the word a “pothole”, with over 570 feet of ladder climbing in its total depth and only about 200 feet of horizontal sections. A really superb hole, with one or two terrifying places which, one might say, ‘add spice’.

Notes on the Survey

Plan. The main plan of the pothole (top left on the drawing) has been made in three horizontal sections which should be superimposed upon each other as indicated by the arrows. Individual sections of the plan are interposed at their proper levels, indicated by horizontal lines, between the two elevations.

Elevations. The two elevations have been made at right angles to each other through the vertical planes A—B and C—D shown on the plan. The same scale is used in both plan and elevation.

Lettering. The capital letters A to L on the left hand elevation refer to points mentioned in the text.

Part IV: The Eiskogel Hdhle

by J. R. Middleton

It was from two Austrians in the Edelweiss Hiitte, that we learnt of a large and recent discovery, the Eiskogel Hohle, situated to one side of the Eiskogel mountain. The cave was four or five hours’ strenuous walking away from our base, but our friends had so aroused our enthusiasm with descriptions of gigantic caverns, ice rivers and fantastic formations that nothing could stop us from visiting it.

My companion was John Higgs of the Nottingham University Caving Club; we assembled ice axes, potholing gear, concentrated food for two days and set off early from the Edelweisshutte, arriving on the Eiskogel about midday. We spent the next five hours looking for the entrance; once found we could not imagine how we had missed it, it is the uppermost of three in a large cliff face and is some 15 feet high by 5 feet wide. By the time we had found it it was getting late and we were pretty tired so we found ourselves a two-man bivouac cave and slept.

Immediately upon entering the Eiskogel Hohle we dropped six feet on to a pile of snow, compact and slippery. We made our way to the base of this and found ourselves in a small chamber with one passage leading off. This went steeply downhill and round several sharp bends before it levelled out and we came to an ice stream two or three feet wide in a passage about 9 feet high. Soon this passage divided, the left branch was the larger so we followed it. Almost immediately it widened, it had an ice floor about ten feet across and the walls were all covered with small ice crystals which shone like stars when we turned our lights on them. Suddenly we came to a 40 ft. pitch for which we had no tackle so, disappointed, we retraced our steps to the junction and tried the right hand branch which eventually led us to a large shattered chamber with some five passages leading off. After building a cairn to show where we had come in we systematically explored each of these only to find that they all ended in chokes. We again started to retreat but then noticed a small passage off to the right with a hole in one corner. Down this we went to land after ten feet on an ice pool at the end of a medium sized passage which we followed to a T junction. Here we turned left, eventually reaching a good sized chamber with one small tight hole leading out of it from which came a tremendous whistling wind: we were on the right route. A squeeze through the muddy hole, on up a boulder slope and then, suddenly—nothing. We were in the largest underground chamber in Austria and one of the largest in the world.

After surveying the scene for several minutes we found that we were halfway up a wall on the top of a great pile of massive boulders. From here we began laying a trail, using ‘Bronco’ which we can particularly recommend. Once down in the centre of the chamber we found that it was really a gigantic passage; imagine Gaping Gill Main Chamber with the walls not meeting at one end but continuing the same size for over 400 yards; four double decker buses side by side on top of four more double decker buses could travel most of the passage length with ease!

A wide gallery descended off to the left about half way along the main passage, this we followed steeply downhill until at a depth of about 200 feet it finished in a choke which held possibilities; on the way back to> the main passage we went up another which ended in a shaft about 150 feet deep. At the end of the main passage one, by comparison small, led off down to one side; this was the start of the main ice river. We now put on crampons and walked past majestic blue ice columns, under glittering chandelier-like stalactites and through mirror-walled galleries. At one point we spent a very exciting hour hacking our way down an ice waterfall to find even more richly decorated chambers and passages. At this stage, whilst admiring the unbelievable, we relaxed our guard against danger and immediately John slipped; he fell, slid, spun round and round and eventually came to a stop some 50 feet lower down, severely shaken but not hurt. Down a further 50 feet we came to a 30 ft. pitch but luckily we could traverse along one wall and climb down into another very large passage 100 feet across and 60 feet high which again was a massive ice river. Where we climbed down there were many ice stalagmites over 30 ft. high in addition to numberless smaller ones. John, who had also visited the Eisriesenwelt, declared that these formations were superior to those of this previously leading ice cave.

At this point we decided to turn back as the ice river was descending rather steeply. After our previous escapade and as there were only two of us we thought it best to take no further risks. As we walked slowly back we had time to look round more thoroughly than I ever remember doing in a cave, and to take in well all the unforgettable sights.

Epilogue

by D. M. Judson

The last two days at Mahdegg saw a complete deterioration in the weather and the whole camp site gradually turned into a lake. On top of this several of us developed severe attacks of ‘Mahdegg Fever’ and become inoperative. We had snow on the mountain and finished with a desperate de-tackling and surveying marathon on the last Thursday. Camp was dismantled at an early hour on the Friday and the final sorting and packing of equipment completed at Werfenweng.

All in all it had been a disappointing expedition; we had not found the deep system we had hoped for. On the other hand some good trips had been made and I think most of us had enjoyed our three weeks on the Tennengebirge. We had explored two pothole systems that would rank with anything in Yorkshire for technical difficulty if not for aesthetic pleasure, and collectively we had seen some of the finest ice caverns in Europe.