Underground In The Lebanon, 1968 and 1969

by J. R. Middleton

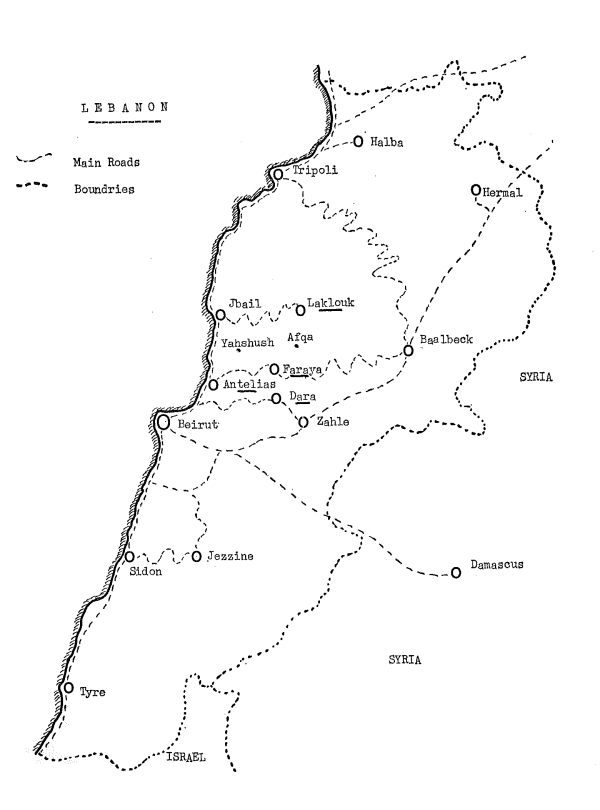

LEBANON—the fabled land of Milk and Honey, of the Phoenicians, the Romans, the Crusaders—country of cedars, gorges and monstrous caverns. My interest was the caverns: drawn by the fact that all but a small part of the country is composed of limestone, even to the tops of its 3,000 metre peaks. I began to make enquiries.

There was a small but very active Speleo Club which had been in existence since 1952, the country contained Jeita, one of the world’s most magnificent show caves, and Faouar Dara, then the seventh deepest pothole in the world. Finally, and a most important point, it still remained relatively unexplored. Contact was made with the Speleo Club de Liban and extremely friendly letters were received, so in August 1968 a small party of four Y.R.C. members and two wives headed for Beirut.

Our main object was to join the Lebanese in a pushing exploration of Faouar Dara and to find out the true potential of the country for a further trip. We more than succeeded in both these objectives; we bottomed their number one pothole at 622 metres (2,040 ft.) and discovered well over 800 metres of new passage and we walked and explored this breath-takingly beautiful country, finding it rich in caves and potholes. Nor did we forget its history; we visited the Phoenician city of Byblos, the Crusaders’ castle at Sidon and several of the well-preserved Roman hill forts.

After such an introduction we could not fail to return and so by June 1969 we were again enjoying the friendly hospitality of the Lebanese. We spent several exciting days amongst the Bedouin in the High Kesrouane area and discovered five new potholes. We visited Laklouk and extended an existing pothole by over 200 metres of very large passage. We also continued our education by seeing the great temples of Baalbek, the destroyed city of Tyre, Beit-ed-Din, the old capital of the Druse, and we made a flying visit to the very Moslem city of Tripoli. But the highlight of our two years’ work came in the last three days: a simple surveying trip into Magharet el Kassarat turned into a new discovery of over 1,800 metres of magnificent stream passageway. Besides being a tremendous discovery for us, it also proved of great importance to the Lebanese since it meant a new and easily accessible source of that most valuable commodity in a hot country—fresh water.

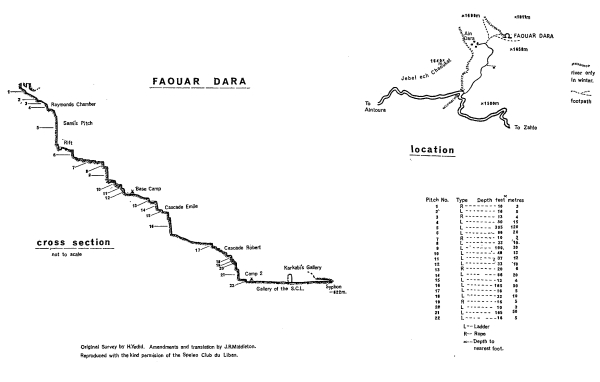

Faouar Dara

The entrance to the hole, at 1,598 m. above sea level, was discovered in 1955 when a preliminary exploration was made to the top of a 120 m. pitch not very far in. No further visit was made until 1961 when a depth of 512 m. from the entrance was reached. A third major attempt was made in 1962 when a siphon stopped further progress at 622 m. A test in 1965 with 50 Kg. of fluorescein showed that the water resurges in two places, one in the sea, the other from a spring at Faouar Antelias about 10 Km. from Beirut and 50 m. above sea level.

Faouar Dara presents a tremendous challenge and the purpose of our 1968 expedition was to explore thoroughly the bottom passages, including a large inlet, and to try to find a way past the siphon.

For three weeks prior to our arrival members of the Speleo Club de Liban had been busy transporting equipment to the hole and as far down it as possible. For our first week-end we continued this operation and laid a telephone cable to a point about one third of the way down. This initial reconnaissance served to test our fitness, which had severely wilted under the scorching Lebanese sun, and to give us a good idea of what we would be up against.

Tuesday, August 6th, was the day of our big push and at 9 a.m. a small convoy of cars bounced up the track leading to the small village of Dara. Here we sat in the shade by the side of a water trough and made our final plans. An advance party consisting of Sami Karkabi, Ghassan Beyhum, Antoine Boustany, Tony Dunford and myself was to set off immediately and a second team, Georges Srouji, Farid Zogbi and Jacques Loiselet would go down about twelve hours later.

We quickly covered the short distance to the cave mouth and set off down the high meandering passage to the 120 m. pitch; only at the entrance and at the terminal siphon is it possible to see the roof. The small chamber at the top of this big pitch was well equipped so that the long stay of the surface party would not be too uncomfortable at a temperature of only 4°C. An efficient hand winch speeded our descent which finished in a deep and beetle-infested lake. Crossing this in dinghies we went down a narrow rift, on to a 20 m. pitch, through a twisting passage, over small lakes, down short and long pitches, arriving eventually at the place where all the kit bags had been left on previous week-ends. This was just past Base Camp Chamber where earlier expeditions had made their first camp, but our object was to reach the bottom camp in one hard push. Hard it certainly was; apart from carrying six kit bags each, the passage, after a beautiful 50 m. pitch, became monotonously repetitive. It was “load dinghy, cross lake, unload dinghy, go back, load dinghy, cross lake, descend pitch, load dinghy ad infinitum”. Or so it seemed as there was very little walking, just these numerous little lakes, or ‘marmites’ (cooking pots) as the French call them, followed by short pitches into more lakes. This section, ending with a second 50 m. pitch, took us eleven hours and proved the most arduous part of the whole system.

The second 50 m. pitch was worth seeing because of the incredible fluting of the top 20 metres, though we were really too exhausted to take proper note of it on the way down. A short passage led from the enormous chamber at the bottom of this pitch to a further short drop into a lake and at the other side of this we came to the second dry place in the whole pot; here was to be our camp, a shingle bank just ten centimetres above river level. After twenty-six hours of strenuous caving we could have slept in the water.

A solid twelve hours’ sleep recharged our batteries and after breakfasting and contacting the surface we set off for the unexplored inlet 100 metres downstream. The river coming down this proved to be larger than the one passing our camp and after 150 metres of easy going we were on new ground. We went through a tunnel and into a large and well decorated passage which we named ‘Khawam’s Gallery’ after the instigator of our expedition, who had been killed in an accident just six weeks before our arrival. The passage divided and we followed the larger branch for 470 metres; it was roomy and in places well decorated but finished in a low and wide siphon. So we returned to the junction and went up the smaller ‘Paradise Gallery’ which we found to be much more sporting: it contained waist deep lakes, high narrow passage, low wide passage and wondrously decorated walls and roof throughout its 275 m. length. The finish was again a low and impenetrable siphon.

After surveying all the new passage we went back to the main river passage, ‘Speleo de Liban Gallery’, and down its 500 metre length to the siphon. This was definitely a ‘no go’ as far as we were concerned as it was quite large and deep, though it looked promising for cave divers. We made a thorough search on the way back but were again unsuccessful, finding only a muddy and rather unstable inlet about 60 metres long. We did however climb a yellow flowstone cascade into a large chamber 60 m. long and 45 m. wide, its height immeasurable but rising 10 metres at the end to a flowstone wall down which tumbled a stream. At the top of the cascade leading to the chamber we found an area containing many cave pearls each in its own basin.

After a short sleep we packed up and started the return journey which was arduous but uneventful. Within 15 hours we were back in Base Camp Chamber and after another very brief rest we started the ascent towards the surface. Not far from the top of the awkward 30 m. pitch we met the relief party who took over our loads, so from there we raced for the entrance. We surfaced at 9.30 p.m. on Friday, the 9th of August after 84 hours below, to be met unexpectedly by cameras of Press, Television and Films, for whom we had to make four repeat exits.

Magharet El Kassarat

The fluorescein test at Faouar Dara showed that part of the water resurged near the Casino at Faouar Antelias just north of Beirut. An exhaustive search of the surrounding area was made, but without success until the early spring of 1969, when the limestone quarry immediately above Antelias broke into the roof of a large passage 14 metres wide and 20 metres high. The Speleo Club, which has excellent relations with the populace, was informed and a small team went to investigate. There proved to be two entrances, both of them pitches; the easier one 13 metres to a cone of rubble. At the bottom was a large but very muddy passage; this was first followed on a rough but generally downward course for 230 metres to a deep siphon. The other way led through 598 metres of even larger galleries and chambers, the smallest place in the whole system being 4 metres square. The end was on the top of a mud and sand choke in which bones were found, suggesting a blocked connection with the world-famous prehistoric cave of Ksa Akil, also in the quarry.

Nothing further was done until Sami Karkabi suggested that on an off day we might like to visit the cave and see what we thought. This ‘off day’ was only three days before we were due to leave for home. Bill Woodward and I went down with Georges Srouji and Sami, expecting a rather easy and unexciting trip. First we went to the upper end and surveyed back, arriving in about four hours at the place where the siphon should have been, but it was no longer there, it had completely dried up. We stopped and looked at each other, then in the silence we heard the dull roar of a distant river. We dropped everything, ran into the empty siphon, up the other side, over a mud bank, round a corner, into a large chamber and we were there—by the side of the raging Faouar Dara river. To the left it vanished down two impassable shoots but upstream there was nothing but an enormous passage challenging us to follow. We took up the challenge and after wading through the river over a much eroded floor for 140 metres we came to a lake. Sami took off his clothes and swam round a corner for about 40 metres to where he could hear a cascade; when he came back we decided that we would need dinghies, ropes and other equipment before we could safely cross this lake.

We returned next day laden with four kit bags and quickly made our way to the lake. Georges and I set off with two bags in the first dinghy and made easy progress for 70 metres to a constriction where the water gushed through with considerable force. With our minds only on all the new ground still to be discovered we pulled our way up the right hand wall to a calmer section—or so we thought, but next moment our boat swung sideways and we were thrown into the cold torrent. Luckily we were both swept to either side but it was a terrible blackness until Georges managed to get his light going again. We then found that the bag containing the ladders and rope had irretrievably sunk; this meant that we could no longer progress up the cascade just 18 metres away.

We began a rather dismal return, surveying as we went and it was whilst doing this that we discovered the utterly fantastic ‘Upper Gallery’, reached by a mud slope climb from the river. The gallery was dry and its entire 120 metre length was crammed with every formation imaginable from monstrous stalagmites to delicate crystal flowers and helictites.

Our last day day dawned and again we attacked; Sami dived with his aqualung and surfaced first time with the missing bag—a good omen. Within half an hour we had fixed a line round the wall and to the top of the cascade and were continuing our pursuit of more passage; fifty, a hundred, two hundred and twenty metres of gloriously meandering stream passage, to a boulder choke. We climbed this into a large oxbow where we discovered two delightful grottoes amidst a chaos of house-sized boulders. The way then descended to a large sand-covered passage gradually increasing to 35 metres wide and 15 metres high; a small stream entered from the left, crossed the sand and joined the main river which had re-appeared only to race down a narrow channel into a siphon. Upstream continued as a large lake, so before unpacking the dinghies we decided to look at the small inlet. After only 45 metres this looked as if it would finish in a siphon as the roof came down to within one metre of the floor, but no, it rose abruptly into a beautiful passage with a stream running down the centre, mud banks on either side and a perfect half round roof. We left the stream after 90 metres and entered a chamber 57 metres long and up to 20 metres wide finishing in a calcite floor of incredible beauty containing, at a very conservative estimate, over a thousand cave pearls, a hoard such as none of us could ever have seen before.

We skirted round this masterpiece of Nature and raced on, soon coming back to the stream, then a further 175 metres of passage to a junction. Straight forward was the larger so we followed this into a chamber containing a deep lake with no other inlets. So back into the other side passage and under a 3 metre high natural rock bridge leading into a classic fault passage at an angle of about 60° (see plan sections) starting at 5 metres high and 4 metres wide, gradually enlarging in a straight line to 20 metres high and 20 wide, but with a steep boulder slope going from the base of the right hand wall to half way up the left. This passage suddenly finished after 90 metres and closed down to only crawling height; Georges, who was well in front, explored it for a further 50 metres into a low chamber with no exit.

This rather muddy looking ‘little’ inlet had taken up more of our time than we anticipated and, after surveying back to Main Stream Passage we regretfully had to abandon thoughts of further exploration upstream and make for Beirut and home. However, with 1,800 metres of totally new passage to our credit we could not really be disappointed. The Speleo Club de Liban must now have a challenge which will keep it occupied for some time; this very large passage system is still 970 metres below the siphon in Faouar Dara and 22 Km. away in straight map line, with only the same limestone formation between.

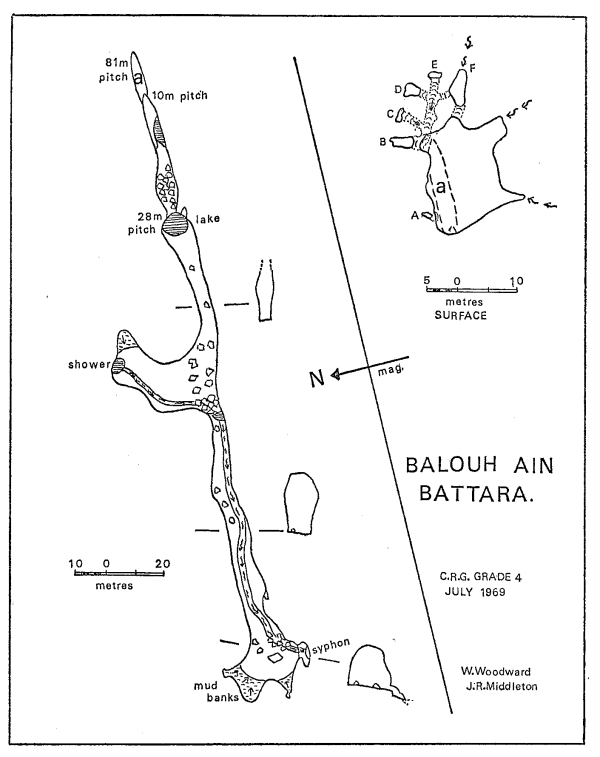

Balouh Ain Battara

On the road leading to Balaa from the ski resort of Laklouk is a signpost inscribed “Point Naturel. Gouffre”. Across two fields and at a point where three dry streams meet is a small outcrop of sharply eroded limestone in the middle of which is a magnificent shaft surrounded by six smaller ones. Sami Karkabi had once before explored this system to a definite choke at the bottom of a 30 m. pitch but he explained to us that something might have changed; during last winter he had visited the pot one week-end when it was half full of water and again the following week-end when there was none.

So, with a large support party under Albert Anavy, Sami, Bill Woodward and I descended this rather horrifyingly impressive entrance shaft at point A (see plan). This is a free hang of 40 metres to a ledge, then 41 metres against the wall into a rift at one end of which is a twisting 10 m. pitch which took us into the darkness, over some boulders and to a 28 m. pitch. We found it best to descend this for only 20 metres and then to traverse along a ledge on to a calcite slope and so avoid the lake at the bottom. The other side of the lake was where Sami had finished last time, but now there was nothing but a smooth floored passage 4 metres wide and higher than any of us could see.

We moved down the passage and into a large chamber at the end of which cascaded a fair sized stream. Downstream was a 3 m. clamber down boulders to the side of a small lake, then a large easy passage for 120 metres into another big chamber. In front and to the right of us were mud banks rising 10 metres up the walls while to the left the roof came down to within 1.5 metres of the floor on the edge of a 1 metre drop into a small chamber. Here the floor descended steeply over shingle to an impenetrable siphon; a disappointing finish but a magnificent new streamway.

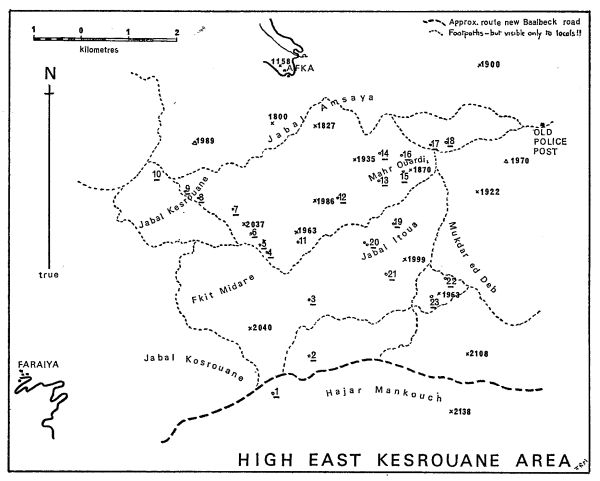

The High East Kesrouane Area

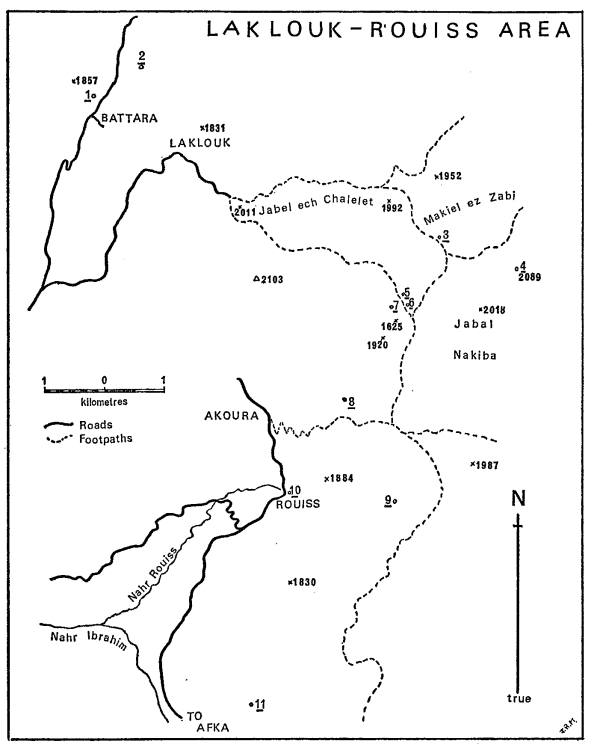

Situated high above the picturesque township of Faraya at the 1,800 to 2,200 metre level lies a barren and desolate region inhabited only by the occasional Bedouin. Gently rolling hills of dazzlingly white shattered limestone sizzle under the unfiltered sun and sparse patches’of green consist only of spiky thistles or an occasional eccentrically shaped juniper. We visited this area twice; the first time on a reconnaissance when we covered some 24 Km., looked at 9 known holes and discovered for ourselves, without really trying, 5 new ones. On our second visit we descended some of our own new pots and one noted by the Lebanese but not explored. The size of the pots so far discovered in this area varies from a few metres to the giant Bedouin Pot (Houet Bedawiye), No. 11 (see map) which is 205 metres deep in one drop. There is little horizontal development, possibly because all the beddings are very close together. For the position of each pot see the corresponding number on the map.

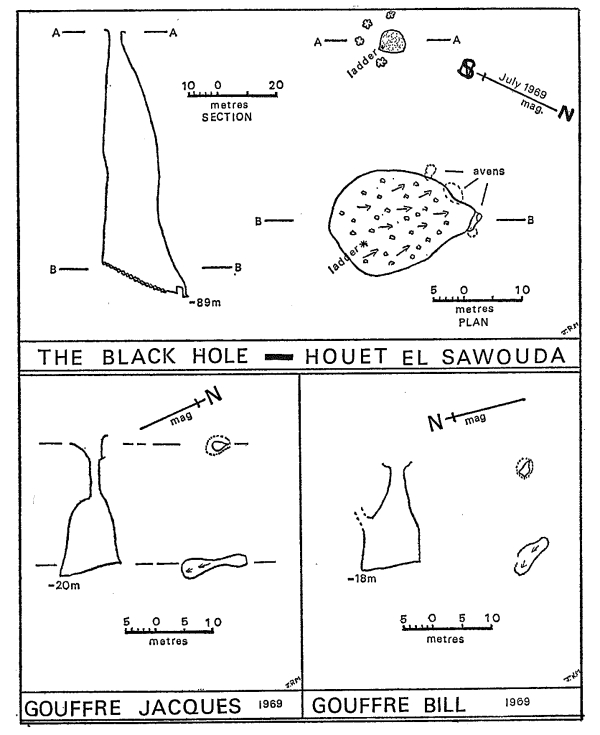

The Black Hole (No. 18)

This pot was the main object of our trip to the area; it had been previously noted, but not descended. The entrance was impressive and had a welcome surround on one side of five cool junipers. The shaft, down which each of us went in turn, proved to be 80 metres of just free hanging ladder on to a pile of boulders 9 metres high. An interesting thing about this pot was that whilst the northern side walls were solid rock the southern side was composed almost entirely of a friable small pebble conglomerate.

Gouffre Jacques (No. 17)

After the descent of the Black Hole, Georges, Janet and I visited this small pot at the bottom of the valley by the side of the main footpath. The entrance looks like a fairly recent collapse and was very loose; it leads to a straight 18 m. pitch down a rift into a small chamber.

Gouffre Bill (No. 13)

A discovery by Bill Woodward almost on the top of a hill. A small but solid entrance and a drop of 18 metres into a good chamber with a few mud-coloured calcite flows and a further small aven at one side.

Gouffre Janet (No. 14)

Again named after its discoverer and consisting of an interesting collection of four open potholes within an area of 50 square metres. The first shaft we descended was between some boulders and was 35 m. deep ending in a small chamber containing some good flowstone. Shaft 2 was only 15 m. deep but had a squeeze leading off which became too tight. The third one was only 2 m. deep and the fourth was 28 m.; only Chassan descended.

Gouffre de Sentier (No. 22)

An open and easily accessible pot which we discovered and descended on our reconnaissance day; it is only 8 m. deep and can be climbed at one end. A small cave at the other end contained quite a plug of snow.

Gouffre Shehade (No. 23)

A Bedouin told us of the position of this one; we did not have time to go down it but the shaft looked most promising and it is certainly between 70 and 90 metres deep.

A note on the naming of pots in this area is perhaps appropriate; many of them have been named after people and not after some prominent nearby object, as is usually recommended. The reason is that there are no readily identifiable objects and few of the hills are named; every valley, hill and rock looks like any other.

Grotte Afka

The most impressive of any cave mouth; a large stream emerges from an entrance about 80 metres wide and 40 metres high. Unfortunately this magnificence is short lived as once inside the river siphons. There was a series of small upper passages.

Laklouk—Rouiss Area

Grotte de ain Lebné (No. 3)

On a most spectacular three day walk from Laklouk to Rouiss in 1968 we visited this cave which is situated just before the junction with another valley. An open pot 5 metres deep leads to a chamber with one obvious way leading off, this continues for quite a distance through mud-covered passages to a sump. Back in the chamber a not so obvious passage leads to a stream which can be followed upwards for about 650 metres through a well decorated stream passage into a large chamber with the stream cascading down at one end. There were also two side passages which we explored for short distances.

Ein el Jozz (No. 5)

The entrance to this cave is at the top of a side valley, a stream flows out of it. Exploration of the cave made an extremely beautiful, impressive and sporting trip; it finished with an impenetrable squeeze about 500 metres in.

Grotte Rouiss (No. 10)

This, the source of the River Rouiss, is impressively set into the base of a 200 m. high cliff only 50 metres from the roadside. It consists of an absolute maze of passages totalling well over 1 Km. in length. At only one point did we find it possible to descend to the stream and even then we could not follow it. The potential in this cave is fantastic if a new way can be found.

Grotte Jeita

This is a show cave about 21 Km. north of Beirut and is the source of the Nahr el Kelb (Dog River). It is difficult to imagine a cave of greater beauty than this one. It consists of two sections, an upper abandoned gallery and a lower river gallery. Both are magnificently decorated and we were lucky enough to visit the further reaches of both on two trips. The upper section was easily visited and we did it all in an afternoon though we could have spent a week admiring the helictites. The lower river gallery is 6,200 metres long and of this we managed to do about 1,000 metres of extremely sporting passage.

Acknowledgement

I cannot finish this article without expressing our sincerest thanks to all the members of the Speleo Club de Liban and especially to the President, Monsieur Ahmed Malek, for all the kindness and hospitality which so much helped to make our two expeditions such an outstanding success. In particular we wish to thank them for allowing us to use their Club House in Beirut, for nursing us all through an attack of food poisoning, for allowing us the use of their equipment, for being our constant guides and companions and above all for becoming our friends.

Members of the Expeditions:

William Woodward 1968 and 1969

Mavis Woodward 1968 and 1969

John Middleton 1968 and 1969

Janet Middleton 1968 and 1969

Trevor Salmon 1968

Anthony Dunford 1968

David R. Smith 1969

Maps

On the maps of the High East Kesrouane and Laklouk— Rouiss areas hills are marked with a cross and their heights are given in thick type, in metres; potholes are marked by a circle and the number beside each circle refers to the pothole given in the following list, which shows the name if given and the depth is explored.

High East Kesrouane Area

1. Gouffre de Tournant 60 m.

2. No name 12 m.

3. No name

4. Houet Joe 25 m.

5. Houet Kandriss 90 m.

6. Grotte Gouffre 50 m.

7. Gouffre Rectangular 25 m.

8. Houet el Kantara 12 m.

9. No name 20 m.

10. No name 10 m.

11. Houet Bedawiye 205 m.

12. Gouffre Elias

13. Gouffre Bill 18 m.

14. Gouffre Janet (4 pitches) 37 m. 15 m. 2 m. 28 m.

15. Gouffre Ignoble

16. No name

17. Gouffre Jacques 20 m.

18. The Black Hole 89 m.

19. Gouffre des Chaucas

20. Houet el Atoura 120 m.

21. No name

22. Gouffre de Sentier 8 m.

23. Gouffre Shehade

Laklouk—Rouiss Area

1. Three Bridges Pot 180 m.

2. Balouh ain Battara 152 m.

3. Grotte de ain Leoné Cave, length 1 Km.

4. Houet el Ahak

5. Ein el Jozz Cave, length 500 m.

6. Name not known Cave, length 50 m.

7. Name not known Cave, length 20 m.

8. Neba Rechme

9. Name not known

10. Grotte de Rouiss Cave, length 1 Km.

11. Houet Saroun