In Memoriam

Since the publication of the last Journal the following members have died: R. de Joly (Honorary Member). W. Allsup, A. L. Middleton, D. Shaw, H. P. Spilsbury, H. G. Watts.

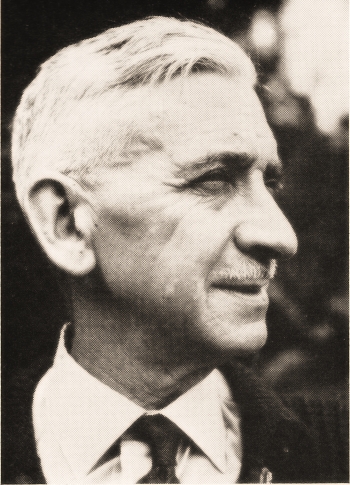

Robert de Joly

Founder-President of the Soctete” Spel6ologique de France, Chevalier de la Legion d’Honneur, 1950 (Military), Officier de la Legion d’ Honneur, 1967 (Speleology), Croix de Guerre, writer of four books and 150 articles on Speleology, Honorary Member of the Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club since 1946, Robert de Joly died on the 11th of November, 1968, at the age of 81 after a short illness.

Second only to Martel, de Joly was, between 1925 and the outbreak of the second World War, the leading personality in French speleology. Born in Paris in 1887 of an old Cevennois family, he developed at an early age a preference for the ‘Midi’ and whenever possible he used to visit his grandparents on the Causses, the limestone district of the Gard. It was on the family estate on Causse de Montdardier that at the age of 14 he made an interesting archaeological discovery in a cavern. As soon as he had got his Engineer’s diploma at the Ecole d’Electricite” de Paris he made his home in the south, first at Marseilles, later at Uchaud and finally at Orgnac in the Ardeche.

Throughout his long life de Joly had three ruling passions; the first was aviation and even more so, motor cars. In the early years of the century he used to take part in motor rallies on the dusty roads of the period and in the last year of his life he acquired a superb Porsche which he used to drive round the twisty roads of Ardeche at 200 Km. per hour. The second was firearms, especially pistol shooting, at which he excelled. It was not until he was in his forties that he began seriously to devote himself to the third and eventually the strongest, the exploration of gulfs and caverns.

In 1930 he founded at Montpellier the ‘Spel6o-Club de France’, in 1936 to be renamed ‘Societe Speleologique de France’, and at the same time he revived the publication of the revue ‘Spelunca’, started by Martel in 1895, but lapsed since the 1914/18 war. It was thanks to his enthusiasm and energy that French speleology so quickly got back on to its feet after the second war.

de Joly served in both wars, he finished that of 1914/18 as Lieutenant de Train, in charge of horse-drawn mountain supply columns, in the second war he was a Captain in the Armee des Alpes.

His most active years were probably 1934 to 1936; in 1934 he made 45 first descents, 27 in 1935 and 30 in 1936. In 1935 he made the great discovery of Aven d’Orgnac, a cave with which he was to be closely associated for the rest of his life. Many of his later years were spent arranging Aven d’Orgnac as one of the finest show caves in France. The part open to the public is only about one fifth of what is now known; much of the exploration into systems Orgnac II, III and IV has been done in recent years by J. Trebuchon and it was he who, on 7th May, 1967, arranged an 11-hour expedition to show de Joly, who had just celebrated his 80th birthday, some of the wonders of these new systems.

Five senior members, one of them a doctor with his medical kit hidden in his knapsack, were detailed surreptitiously to help the Guest of Honour, while at a discreet distance followed a team of younger members with cave-stretcher, splints, cases of instruments and reanima-tion equipment. When well underground de Joly showed them that he carried his own reanimation equipment—a little flask of superb white wine. At the point in Orgnac III at which it was considered prudent to turn homewards de Joly, after some remonstrance (he wanted to see The Sugar Loaf at the very far end of Orgnac III) said ‘Vous assistez a mon agonie sportive. C’est ma derniere expedition. Je la savoure.” (“You are witnessing the death-agony of my hobby. This is my last expedition. I am relishing it.”)

It was only three days after the event that the writer had the great pleasure of meeting de Joly and of being shown not only Aven d’Orgnac but two other caves in the district. He was thus able to see at first hand the energy with which his host led him underground to depths of 125 metres and distances of 1,000 metres, the skill and intrepidity with which he drove his motor car and his readiness to give his guest some sharp advice as to how he should drive his own Lancia Flavia.

de Joly was not only a forceful and accurate explorer and surveyor of caves, his engineering training was in constant use to devise new and to improve existing equipment. In his home he had a fine workshop and many of the improvements he introduced into general use in caving were the work of his own hands. He always carried in his pockets even when wearing dress clothes, an array of diminutive tools with which he could deal with any emergency. The story is told of a Congress at which he was President. After a morning devoted to the official opening, the company was to reassemble at 2 o’clock for the inauguration of a speleological exhibition. The organiser, with the safety key of the exhibition hall in his pocket, was detained after lunch and arrived after a serious delay in a state of great annoyance at having kept the President waiting. To his surprise there was nobody outside the door, which was ajar; inside was de Joly lecturing the assembled company about the exhibits. Apparently de Joly, precise as always, had arrived at 2 o’clock and, after waiting a quarter of an hour, had produced from his pocket the appropriate tool and picked the lock.

It was as the result of his work on ladders that he first made contact with the Y.R.C.; some of the correspondence between him and E. E. Roberts has survived the years. The first letter, from de Joly, dated 3rd December, 1932, is addressed “Monsieur le President du YORKSHIRE RAMBLERS’ CLUB, LEEDS, Angleterre,” and in it he deplores the lack of acknowledgement of his several letters and brochures; he says he had hoped to establish close and useful contacts with our Club. To this Roberts, at the request of the President, W. V. Brown, replied, sending a copy of Y.R.C. Journal No. 20 and giving the Club’s correct address in Leeds, 10 Pavk Square; there followed an immediate reply from de Joly describing his work over the previous two years on ‘ultra-light’ ladders. Compared with the weight of 1 Kg per metre for the rope ladders with wooden rungs in general use at that time, he used ladders weighing only 570 grammes per metre, with a breaking strain of 600 kgs, with nickel/chrome rungs and fitted with ‘instantaneous’ couplings, also in nickel/chrome, for joining one ladder to another. As ropes he used safety line with telephone cable woven into it, his boots were chrome leather dressed with tallow and fitted with special crampons which he claimed were far superior to tricounis.

The correspondence went on and in 1937 de Joly reported that he had now made ladders of 46 grammes per metre instead of 90, he asks whether the Y.R.C. are using them. Then comes an interval of nine years; the next letter is dated February, 1946, de Joly asks the name of our President, they wish to make him an Honorary Member of the Societe” Speleologique de France. The ensuing correspondence mentions the election of Clifford Chubb to this honour in March, 1946, of Roberts a year later and of de Joly to the reciprocal honour in the Y.R.C. Although he was never able to realise his ambition to join our Club, and especially Roberts, in the caves of Yorkshire, his interest in the Club continued to the end of his life and in recent years he regularly contributed an article for our Journal on Speleology in France.

Great individualist, dynamic leader, meticulous organiser of expeditions, beneath a natural roughness and a sense of authority that tolerated no contradiction, Robert de Joly was described by his colleagues as “a great honest man who never betrayed a friendship.” It was inevitable that his strong, original character should lead to his being violently criticised by some, highly respected by others. One reproach was sometimes made by his own collaborators about his technique of exploration, namely his ideas about the special functions of the leader—first into a cave, first to overcome a difficulty, first at the bottom, last out, sometimes leaving equally experienced fellow-members to jobs on the surface or to shiver for long hours as relays. Quoting the Spanish caver Arcaute “When it’s horizontal democracy is fine, when it’s vertical then it’s got to be dictatorship.” Robert de Joly was certainly always for dictatorship.

H.G.W.

The writer of this obituary is indebted to the Federation Francaise de Speleologie for their permission to quote freely from ‘Spelunca’ 4 me serie, 1968, No. 4, which issue was devoted entirely to Robert de Joly. There are two copies in the Y.R.C. Library.

On a tourist visit to L’Aven d’Orgnac, which was discovered and explored by de Joly in 1935 (YRC Journal 34, p. 249), the Acting Editor saw the memorial urn to de Joly which is set in the main chamber amidst formations of great beauty, variety and size. The speed and accent with which the guide spoke prevented the Acting Editor from fully understanding the tribute paid to de Joly but the respect in which he is held was plainly evident.

William Allsup

With the death of Bill Allsup who joined the Club in 1919 we have lost one of our oldest members.

Because he spent most of his working life in India and Assam he was unable to take much part in Club activities except on his infrequent visits to this country.

Allsup learned his mountaineering and caving with his old friend, E. E. Roberts. He had a true love of the wild and inaccessible places and spent all his short leaves exploring the country round Shillong and the foothills of the Himalaya. He was the moving spirit in the foundation in 1927 of the Mountain Club of India which in the same year amalgamated with the newly formed Himalayan Club. He also wrote and published a book, Notes on Walking around Shillong (1934).

Allsup was a very competent though not outstanding rock climber, leading the V.S.s of those days though hampered by an accident in which a rock fall crushed his foot.

He was a most lovable man and happy companion, holding very definite ideas on mountaineering matters. He did not hesitate to expound these views both by word of mouth and voluminous letters which neither the recipient nor himself was ever completely able to decipher.

On retiring he came to live at Bridge End, Patterdale, but owing to ill health was unable to do much walking. He was however a fairly regular attender at the Annual Dinner and took a keen interest in Club matters.

J.G.A.

Alan Lomas Middleton

At the time of his death on 19th May, 1970, Alan Middleton was the longest serving member of the Club, a distinction which gave him great pleasure. He became a member in 1912 and was Vice-President 1947-48.

He was brought up in a family tradition of fell-walking by his father, Gilbert Middleton, and his uncle, Noel Middleton, both of whom were members of the Club. It is reported that he was taken by his father to the top of his first Yorkshire fell, Ingleborough, at the age of six. Subsequently he spent much time in the hills, particularly on the Yorkshire and Lake District Fells. Notes made by him in his early edition of Baddeley show that in his youth he was a fast mover over long distances in hill country. For many years he had a cottage in Little Langdale as his Lake District base.

Increasingly his business commitments prevented him from taking a very active part in Club Meets, though he continued a regular attender at the Dinner, at Club Lectures and at the Leeds Lunches.

He was a big man of imposing presence but a very kindly man. His friendliness will be remembered by all, but especially by those new members whom he helped to feel at home in the Club from their first appearance at Meets. This kindliness together with his evident enjoyment of the hills and of the comradeship of the Club endeared him to Club members.

The long family connection with the Club will be continued for many years through the membership of Alan’s three sons.

A.B.C.

Donovan Shaw

Don Shaw, who died on 4th May, 1969, joined the Club in 1930. His first visit to Switzerland followed in 1931, and his experiences around Saas Fee are related in his charming article in Journal No. 20.

Always happy in the hills, he also climbed in Skye, North Wales and Scotland. His quiet humour will be long remembered by his friends.

H.S.B.

Harry P. Spilsbury, O.B.E, 1897—1970

On the 14th May, 1970, Harry Spilsbury fell whilst descending Ben Alligin, his head struck a rock and he died instantly. So passed one of the great personalities not only of the mountaineering fraternity but of many other spheres of activity, leaving a host of friends to mourn their loss.

Born 1897, educated Merchant Taylor’s School, Great Crosby, he joined the Civil Service, Inland Revenue Department. During World War 1 he served as a gunner with the British Expeditionary Force, was taken prisoner and spent the last year of the war working in a German coal mine. Returning to the Civil Service he rapidly became Senior Inspector of Taxes in Liverpool, where he remained until his retirement in 1959, when he was awarded the O.B.E. in recognition of outstanding ability. In 1940 he married Ruth Watson who shared his many interests.

The Y.R.C. elected him to Honorary Membership in 1956, and he was, in turn, president of the Wayfarers’ Club, the Rucksack Club and the Fell and Rock Climbing Club. In 1955 he joined the Board of Directors of the Outward Bound Mountain School at Eskdale, Cumberland, subsequently becoming Chairman. Membership of the Management Committee of the Outward Bound Trust and also of the Board of the Ullswater School followed.

Gifted with an excellent baritone voice, he sang in the choir of Christ Church, Waterloo, for nearly thirty years, and was a prominent member of the Waterloo and Crosby Amateur Operatic Society. To the Y.R.C. and several other climbing clubs his singing of climbing songs at our annual dinners gave constant pleasure.

A bold and enterprising mountaineer, perhaps his chief love was for the bare, gnarled, intimidating peaks of the Lofoten Islands and Arctic Norway, where in 1934, 1935 and 1936 he did some outstanding climbs. His article, The Lofoten Islands {Wayfarers’ Journal, no. 5, 1937) remains the best climbers’ guide to the area.

He was an accomplished ski-mountaineer, returning year after year to the Oetzthal and the Stubaithal areas for arduous high level crosscountry ski-ing. The “Haute Route” on skis from Chamonix to Saas Fee was traversed, and he was only prevented from completing it the reverse way by a severe chill.

The fitting and maintaining of climbing huts occupied a great deal of his time, and he was particularly well-known as Warden of the Robertson Lamb Hut in Great Langdale. Here he was looked upon as being something of a martinet and woe betide anyone who left R.L.H. in a mess. Harry told them where they got off without mincing words. Yet there is no doubt in my mind that he set the high standard to which the leading English clubs aspire for their huts. Had it not been for his persistent efforts it is doubtful if the Glen Brittle Memorial Hut would have ever got under way. Due to its remoteness there was difficulty in getting firms to tender, while soaring costs and local restrictions added to the headaches. Only a man of Harry’s tenacity could have seen it through. The joint Meets held at R. L. H. every September, which he organised and catered for, gave enormous pleasure to decades of Yorkshire Ramblers.

To use this tenacity, this thoroughness, this giving of his best to everything to which he laid his hand, was perhaps more than anything characteristic of the man. He was forthright, hated humbug and had no use for dodgers. Yet no man had a warmer personal interest in the affairs of all he met. If asked for advice or help he gave unstintingly, and his knowledge, and skill as a craftsman were entirely at the disposal of those who needed them. He was a delightful companion and a loyal friend, kindly, witty and informed, with a great capacity for enjoying the good things of life.

One who never turned his back

but marched breast forward, Never doubted cloud would break, Never dreamed, though right were worsted,

wrong would triumph, Held we fall to rise,

are baffled to fight better, Sleep, to wake.

H.L.S.

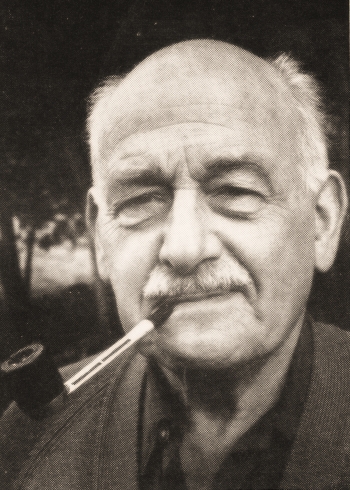

H. G. Watts

Tim Watts was one of the group described by Roberts as “the Stockton men”, who came to the Club in the 1920’s and 1930’s from

I.C.I. After Marlborough, Oxford and Leyden he went to I.C.I, at Billingham in 1927 as a research chemist. He joined the Club in 1932 and, starting under Roberts with surveys in G.G., began to build up an extraordinarily wide and accurate knowledge of potholing—in this country, in France and in other parts of the world. He became a Life-member of the Club in 1967 and was elected an Honorary Member in 1968. He had the unenviable challenge of succeeding Ernest Roberts as editor of the Journal and for twenty years, from 1950 until his death at the end of February 1970, he carried out this task with a happy blend of quiet firmness, efficiency and invariable courtesy. It entailed a great deal of work, some of it tedious and time-consuming, which he did meticulously and willingly; nothing was too much trouble provided it maintained the reputation of the Club, of which he was immensely proud.

I.C.I, had transferred him to Belgium in 1951 and when he retired as Chairman and Managing Director of I.C.I. Belgium in 1963 he went to live in Gstaad in Switzerland His absence from England did not appear to cause any gap in his understanding and appreciation of the affairs of the Club or to limit his editorship of the Journal. Members always looked forward to meeting him at the A.G.M. and Dinner, and his speeches, regular at the first, and occasional at the second of these functions, were a delight to those present.

The occasional meets he was able to attend during these years gave him evident pleasure. He once spent a week-end at L.H.G. on his way back from Scourie, to choose photographs for the Journal and suggested going up Wetherlam because he had never been on it. He explained that his pace would be slow but he was equipped with three types of tablet to offset different intensities of pain. If he took any of them he did so unobtrusively and he was as pleased as a boy when he had reached the top. His doctor was equally pleased shortly afterwards at the state of his heart, until he discovered what treatment Tim had been using He went on gardening, walking and ski-ing, and died in the mountains close to Gstaad, ski-ing in company with his wife. It was a privilege to know him and a pleasure to work with him. His editorship was a great service to the Club.

A.B.C.

His lifelong friend and one-time colleague, Ernest Wood Johnson, has contributed the following:

Tim was a gentle man and this was felt by all who knew him. So, after he had made a typical speech at a recent Y.R.C. dinner, I said to my neighbour, “You’d never think Tim was a wartime saboteur, would you?” The surprise reply to me—who thought it was common knowledge—was “not OUR Tim, surely not.” No, not our Tim, but one of the other Tims. He had many sides, but in the final analysis he was always our gentle Tim.

We were close colleagues in the same department of I.C.I, until 1939. We often went out on the same jobs together and began our association on the hills.

In 1939 he just disappeared. We knew he was in the services, but no more. He was a civilian employed on the oil fields of Rumania with the secret job of preventing the oil wells, etc., falling intact into German hands. I think about this time he was ordered to take a load of explosives to a distant place and blow up something. The quickest way was to fly, but the only available aeroplane was to carry German secret service agents. However, he had already made friends with them—he spoke German from the age of five—so they helped him with his luggage into the aeroplane and out to the waiting car at the other end. That was typical of his disarming ways. Eventually the Rumanians turned pro-German and he had to get away quickly. He happened to be in Belgrade the day it was bombed without a declaration of war. He was driving a car when he saw a bomb fall in the street and roll into the gutter. He thought it was a dud, but stopped, and was getting out of the car when the bomb went off. When he woke up he was lying on the hospital floor, having had no attention, with the left lower side of his face blown off. His instinct was to flee: he was afraid he might fail under Gestapo torture. Going outside he found a bicycle and rode south as far as he was able. The injury sealed his mouth but he was kept alive by means of a rubber tube, pushed through a hole in his face, by people who helped him on the way. Some weeks later he was picked up on the south coast and taken to hospital in Cairo where a series of operations continued his pain and distress. He had a very rough time before he was well again.

Afterwards he took charge of a school for saboteurs in North Palestine where he did his parachute jumps and trained people in mountain warfare, etc. Bill Tilman passed through his hands. Later, and until the end of the war, he was in charge of the school for industrial saboteurs at Morar. The Norwegian heavy water boys were some of his pupils.

The first time I saw him, after the war, he turned up at our office at Alderley Edge on an old bike and wearing even older clothes—war and the S.O.E. seemed to be far away from him. He was the same old modest Tim with only a scarred face to remind us that he had ever been anything else.

He returned to work and made an extremely successful new department from nothing. His staff adored him. For some years we were again close colleagues—our departments were complementary—• and companions in leisure. We continued our week-ends in the hills—brewing up midst the groughs of Kinder, or down Long Churn where he took me and my lame leg for shelter that snowy Hill Inn meet of 1947. He produced ex-army dehydrated shepherds pie and made a monster feed before nursing me through that blizzard to safety on the road south of Ribblehead, and then home. Or in the Lakes at Fell and Rock dinner meets climbing on Kern Knotts, or frying sausages under the crags of Borrowdale. About then I lent him a tent for a week-end at Gaping Gill. It was very wet and he recounted with glee that it was the only one weatherproof, and that an extraordinary number of Ramblers were crammed into it. He could not resist the ridiculous. His own experience, his days on the hills, and his work, were all food for laughter. At home with us he would recount funny stories for hours, and in many dialects or broken foreign languages—his face altering to suit the characters he acted.

His interests were many—he rode to hounds, was fond of rough shooting, sailed boats. In his large garden at Styal he grew many kinds of uncommon flowers and tobacco, which he cured and gave to his friends in cigar-scented blocks. Astronomy, antiquities, esoteric subjects (particularly Ouspensky)—all were fascinating to his enquiring mind, with a kind of detached involvement. He enriched and gave meaning to the common things of life.

A few days after his retirement he and Kay stayed with us on their way to Scourie for the fishing. It was a happy pilgrimage for Tim. As a small boy pre-1914, he had travelled there from Cheshire in his Father’s motor-car, Mam in large hat and veil and dustcoat of those days. He still used his father’s rods, bought last century, and we overhauled them for the occasion. It was his father who called him ‘Tim’ from babyhood.

I have been his guest at so many Y.R.C. dinners, that when he was made an Honorary Member a year ago I felt one too!

One of our recent perfect days was cutting up Kilnshaw Chimney to the blue and white line above. Then lounging under a rock below the top of Red Screes drinking whisky-sloshed tea and watching the sun go down over the sea, waking “late amber shadows in the sleeping grass”. A moment of quiet contentment.

On the Monday after the last Dinner Meet we went to Kentmere to see the Driscolls—but they were away. So we walked in the sunshine up the frozen valley. Tim was entranced and immediately began making plans to bring Kay to that delightful place. On returning home he solemnly greeted Anne with the empty sandwich box and said “There was no cake”. There was no telling when or where the little monkey would escape! Next morning at Arnside station we waved him farewell.

“With a ticket through to Berne, and regarding his profession with a lordly unconcern”.

That’s our Tim.

ERNIE WOOD-JOHNSON.