Iran: A Caving Adventure Extraordinary

by J. R. Middleton

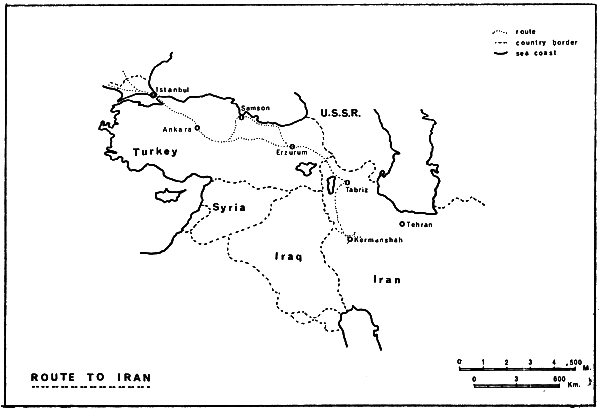

The object was to reconnoitre the virgin limestone mountains of the North Zagros in Western Iran as a potential caving region. The added bonus was to motor over nine European countries, across the intoxicating highlands of Eastern Turkey and then down through the expansive beauty that is Iran.

It is not easy knowing exactly where to start recounting an adventure with so many experiences. From the jumble of life in Istanbul, from the spellbinding views of a sterile salt lake, or perhaps the problems of “Farsi” road signs or then again maybe to start with the end—the discovery of Ghar Parau, 2,383 ft. deep, still going and already the deepest cave in Asia. Best to save that until last and start at the beginning.

The Idea

The concept of caving in Iran originated as an extension of my previous activities in Turkey and the Lebanon. I knew that parties were already planned for the Himalayas but as far as I could find out none had been for Iran, and none was projected. Why, I do not know, as very little research was needed to find one range of mountains almost 800 miles long composed almost wholly of various limestones.

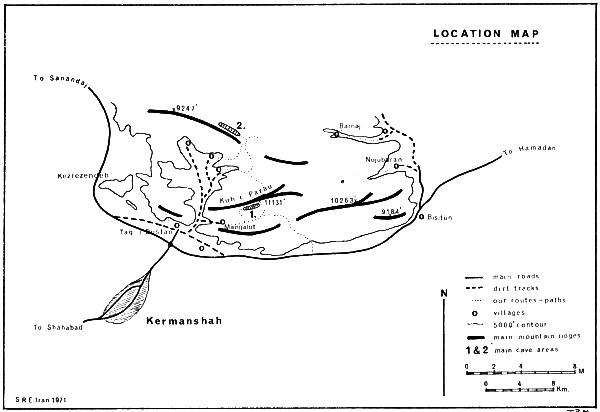

Further questing with the help of geological maps published by the “British Petroleum Company” helped to pinpoint an area almost 60 miles long stretching from Kermanshah westwards to the Iraq border. The mountains were of the middle and lower Cretaceous ages and the maps showed our area as being particularly massively bedded and exhibiting karst features. The idea was then put into action and within a few months an eleven man caving team was organised including Glyn Edwards and David Judson of the Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club.

The Journey

For transport we used a short wheelbase Land Rover and a hired 30 cwt. Commer van. The 1,800 mile journey to Turkey took us just 52 hours of almost non-stop driving and my only recollections of this section of our trip was of a breaking dawn in the mountains of Austria, of a monotonous day crossing Yugoslavia’s vast plain and of a magnificent daybreak as we descended from the mountains into Bulgaria. After a swim in the Sea of Marmara we headed for the early morning rush hour of Instanbul. Rush it was, we were jostled along at 50 m.p.h. through narrow winding streets, down wide boulevards, past mosques, exotic bazaars, crowded shops and finally into a street teeming with life, leading to the ferry. The crossing was uneventful but extremely interesting as we had to wind our way between submarines, destroyers and high speed launches.

The distance to the Iranian border from Istanbul is about 1,300 miles and it is in the last half of this that one first begins to realise that home is far away. Everything is so different. The roads become narrower and in some places just dirt tracks. Cars are a rarity and oncoming lorries threaten dangerously. The distance between towns lengthens and we could sometimes travel an hour or more without seeing a soul. The mountains grow bigger and the passes higher. Nature’s marvels go by in increasing frequency—dazzling white salt lakes, oppressive gorges, incredible rock formations, spectacular vistas and burnt up plains. Turkey’s farewell is an hour long view of the snow-capped Mount Ararat guarded by the mounds of seemingly impassable badlands.

If we thought that Eastern Turkey was thousands of miles from home then the moment we crossed into Iran we might have been a million miles away. The people had different features, they were more inquisitive but much friendlier. All the signs were now in “Farsi”, written in a form of Arabic which defied our attempt at translation but added considerably to the sport of “navigation”. Everything seemed to be on a much grander scale—we entered a wide but precipitously sided gorge just after Basorgan which occasionally revealed expansive views of mystic mountains. This valley we followed almost to Shahabad where the scenery gave way to extensive lowlands before descending onto the flatlands leading to Tabriz.

We now turned off the main Tehran road and headed south past the tantalising but unreachable Lake Reza’iyeh. Tantalising because although the heat was unbearable the water was just too far away to reach. At one point long fingers of salt did stretch to the road but the actual water remained as far away as ever. The next town of Miyandoab saw us make our first mistake when we took the road towards the Turkish frontier instead of the one to Saqqez. We were stopped by an English speaking Iranian about one hour out who, after surveying our dispirited state (at least an inch of dust on all of us) invited us back to Miyandoab to clean up and spend the night at his house. An incredibly hospitable gesture which was appreciated by all of us and proved to be typical of the majority of Iranian people we met.

The next day saw us revitalised and on our final stretch. Through more hot, dusty and inquisitive towns, down to the fine Gonbad River gorge and then we had our first views of the impressive massif at the far end of which our objective, Kuh i Parau, was situated.

Problems

We had originally intended, by deductions made from our maps, to camp in the large valley behind Taq i Bustan but, in spite of there being several small villages, water was nonexistent save for an odd very sluggish and muddy spring. We searched along the base of the mountains towards the bas-relief of Darius at Bisutan but without success. That first night and the second we spent behind the Highway Patrol post on the main road camping on two inches of dust. On the third day in desperation we decided to ask for help from the Governor of Kermanshahan Province. Our first visit in our best but rather battered clothes found him at lunch, at our second we were requested to return the following day but the third brought unbelievable success. The Governor showed considerable interest in our project and offered us the use of one of his private estates at Kezrezendeh, some 15 miles north of Kermanshah. He also offered us all the assistance we might require through Mr. Abrahimy, the Director of Radio and Information who acted as our interpreter at the interview.

The Camp, The People

Kezrezendeh was Paradise; it consisted of a deep resurgence pool some 100 yards by 50 situated at the base of a 6,000 ft. high craggy hill. The pool was surrounded on its other sides by lush level green fields edged in the distance by the subsidiary peaks of Parau.

We really met and came to know the local villagers and tribesmen on our first Friday when we learned that the place where we had pitched our tents was also the place where they held a weekly dance. At 8 a.m. (four hours after eight of us had left for the mountains) a steady stream of Kurdish people began to investigate the camp and the remaining slumbering trio. By 8.30 nothing could be seen of the camp except a heaving mass of brightly dressed women and inquisitive men. At 9 a.m. amid excited drumming and frantic fluting, traditional Kurdish dancing got under way some fifty yards from our tents continuing unabated until dusk.

The Kurds we found the most interesting people we had come across. The women were extremely pretty and showed themselves off in glittering dresses and decorated hair. They never wore veils, unlike the peoples just south of Kermanshah or those 100 miles further north. The men, whilst not so brightly clothed, wore a very distinctive and individual dress. All, without exception, were immensely friendly and would always give but never accept.

Exploration

Each day we would split into two groups, one to explore around the base of Parau whilst the other attempted to cover as much of the mountain as possible. The very high temperatures (it was often up to 100° F. by 10 a.m.) necessitated starting our day well before dawn so that the mountain party could gain coolness with height. The valley party were only able to explore in the early hours before being compelled to seek shelter from the sun.

All the same, the valley team were the first to report any form of success when it added to the Kezrezendeh resurgence four more major springs. Moving eastwards round the mountain these were at Taq i Bustan, Bisutan, Barnaj, and Nujubarin, all sites of small villages around the 4,000 ft. to 4,500 ft. level. Unfortunately in all cases the water rose from depth and never came out of actual caves. No entrances of any sort were in fact found at or near valley level.

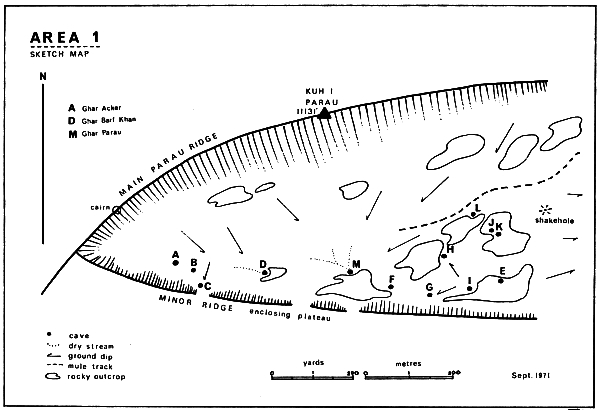

The uphill parties, whilst slower in first making any discoveries, were eventually much more successful when two plateaux were found each with numerous shakeholes. The first was situated immediately below the summit of Parau at a height of 10,000 ft. and the other about three miles north (marked Areas 1 and 2 on the map).

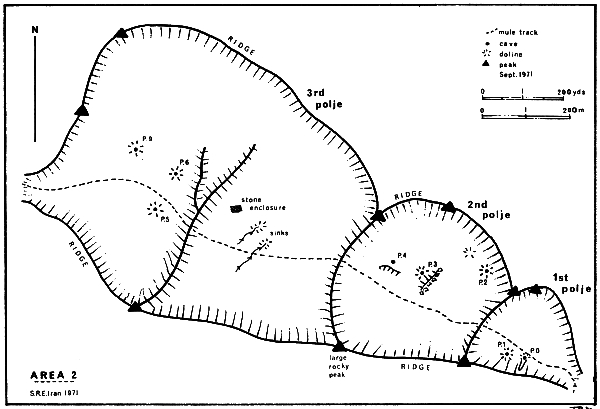

Area 2

This was visited twice, once when it was discovered and then again on a two day pushing camp. To get to it we followed a steeply ascending donkey track at the north east end of the valley for some 3,500 ft. vertical. When the track eventually levelled out we entered a series of stepping poljes, each containing numerous shakeholes, several shafts, and many other karst forms which made the areas very interesting to explore. As I only descended a few shafts in poljes 1 and 2 the following descriptions are taken, in the main, from the notes of Peter Standing who led the second camping trip.

Cave Descriptions In Area 2

P.0. A large depression on the north side of the track at the end of a subsidiary valley. This terminated as a thirty foot shaft leading into a small chamber with three passages all blocked by boulders.

P.1. About 150 ft. further along, this hole was found with some difficulty at the base of some fine rock flutings. It consists of a 60 ft. entrance pitch followed by a further pitch which proved too tight to enter.

P.2. This was the largest shakehole in the second polje and has a tight entrance leading to a steep boulder slope finishing in a fifteen ft. and twenty ft. pitch down to a choke.

P.3. Immediately beneath an enormous boulder at the base of a small cliff is a 50 ft. pitch. At the base of this a northward passage continues to another choke.

P.4. Towards the third polje at the base of a small crag is a blocked twenty ft. shaft.

The track into the third and largest polje passes two dry stream beds, the first sinking in mud and the second sinking in boulders over what seemed to be a shaft. A small ridge crosses the polje and on the other side are more holes.

P.5. A large shakehole south of the path with a 24 ft. pitch, choked.

P.6. An even larger shakehole to the north of the path leads to a 60 ft. pitch, this time choked with dry mud.

There were also several other shakeholes but none containing any more open shafts, although, continuing further up the mountain one member did claim to have seen more holes.

Peter Standing also led a reconnaissance to the north side of Kuh i Parau by following the most easterly arm of the main valley until it curved round and headed in to the mountain up an impressive gorge or “tang” as the Iranians know them. To use Peter’s words, the “ascent of this, which provided sporting climbing, eventually leads to a broad fan shaped slope immediately below the sheer summit faces. Two potholes were found here, one of 60 ft. and the other of 95ft. The latter has an ice plug at the bottom.”

Area 1

A reconnoitering party led by David Judson stumbled across this incredible plateau at an altitude of almost 10,000 ft. but did not have sufficient time to do more than note a few entrances. Shortly afterwards a second party armed with ropes and ladders made the ascent to the caves and were successful in discovering Ghar Acker as well as several shafts. The potential was now proved so a further camping trip was organised, this time with the assistance of three donkeys, a donkey driver and two gendarmes (as supposed protection against supposed leopards). The original route to the plateau was via a 1,500 ft. Very Difficult climb, followed by much sporting scrambling but now that there were donkeys the wayfollowed a crumbling track which zig zagged up to and then across an almost sheer face.

Whilst the path steadily climbs upwards an increasingly panoramic view gradually unfolds as first ridges and then peaks fall below its level. The final vista, which transcends all others, is seen as the path climbs over the last ridge before dropping onto the plateau. It is of untamed magnificence with bare, jagged peaks and ridges in the foreground falling 6,000 ft. to the broad flat Qareh Su plain on which Kermanshah sits and in the distance even mightier mountains than Parau can be seen thrusting upwards through the haze. The scene towards the plateau is none the less impressive and offers a complete contrast of solitude and silence. Low rocky outcrops lead down to a flat green expanse almost 1,200 yards long and 400 yards wide. The whole is enclosed by ridges of varying height climbing to the summit of Kuh i Parau still over a thousand feet above.

On this third visit, Ghar Barf Khan was explored to an unfinished depth of 200 ft. whilst Ghar Parau was descended to a depth of over 700 ft. This proved even bigger than had been anticipated and required more men and equipment so again a retreat from the mountains was made and further plans devised.

The final attack was made by nine men during a five day camp on the plateau. Six donkeys were used to help carry up sufficient equipment. The party suffered two casualties before exploration had properly commenced when Dave Land developed altitude sickness combined with a chest complaint and David Judson contracted an eye infection which necessitated both members returning to the valley.

Cave Descriptions In Area 1

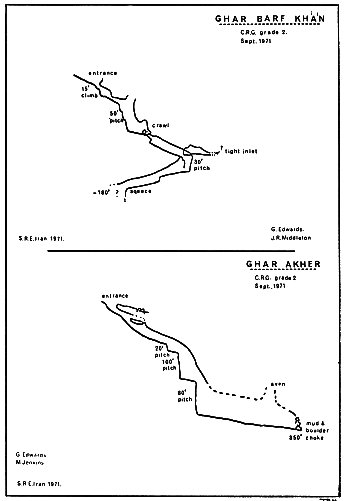

A. Ghar Acker (First Cave). So called as it is the first cave on the western end of the plateau and also the first one to be explored. The entrance is at the end of an oval shake-hole and sports a squeeze past a snow plug onto a loose rock slope leading to a narrow rift. This almost immediately drops 15 ft., but the hole can be bypassed via a side passage which re-enters the rift just before a further 20 ft. pitch. The small chamber at the bottom has another inlet but this proved too tight to explore. Almost immediately a very fine 100 ft. shaft falls into a further chamber with another 85 ft. drop after a short narrow section. The passage at the bottom is almost 10 ft. wide and for the next 200 ft. it is impossible to see the roof. The finish is a loose mud and boulder choke which may repay further attention. Total depth, 350 ft.

B. A boulder filled shakehole through which it is just possible to reach and descend a 25 ft. choked pitch. Total depth, 40 ft.

C. Another completely choked shaft without much hope.

D. Ghar Barf Khan (Snow Place Cave). This was named as such due to its nearness to some stone shelters which bear the name Barf Khan. The entrance is perhaps the most promising looking on the whole plateau as it is free from boulders and consists of a cave type opening. This is followed almost immediately by a 15 ft. climbable shaft with an exit at the bottom over a large block. The small chamber at the other side has two pitches in it, one being 20 ft. and choked, and the other one, after an unstable take off, drops 50 ft. via three steps into a large passage. After 40 ft. this finishes and a two ft. high crawl on the left is the continuation. At the end of the crawl the floor drops away and becomes a tight rift where progress is made by jamming at various levels, the only large section being at a 30 ft. pitch where a small inlet was also investigated. The cave was not pushed to its limit but only to a tight looking pitch shortly after three rather awkward squeezes. Total depth, 180 ft.

E. This is a small ascending cave, 12 ft. long.

F. A completely choked shakehole.

G. A very fine 70 ft. pitch unfortunately blocked by boulders.

H. At the base of a rock outcrop a descending rift closes down just within sight of daylight.

I. It was descended but was estimated to be 50 ft. deep with no obvious way on.

J. The largest open hole on the plateau. It measures nearly 70 ft. long and 30 ft. wide. It can be climbed to its floor 30 ft. below via its north wall. A tight shaft leads off opposite but could only be descended for a further ten ft. Total depth, 40 ft.

K. Situated only 20 ft. away from J. this hole is almost as impressive being circular and 30 ft. in diamter. A 55 ft. pitch drops onto a snow plug. At the eastern end a narrow fissure descends a further 30 ft. into a largish chamber which has no outlet. Total depth, 85 ft.

L. A quite promising sink which runs inwards for 40 ft. to a three inch wide crack.

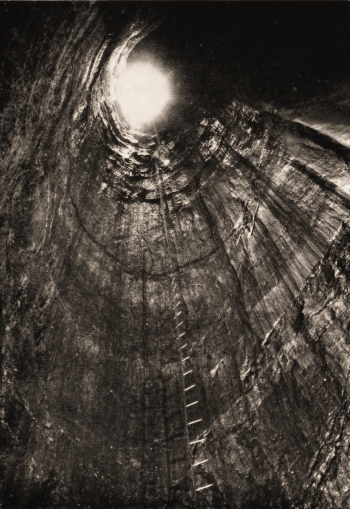

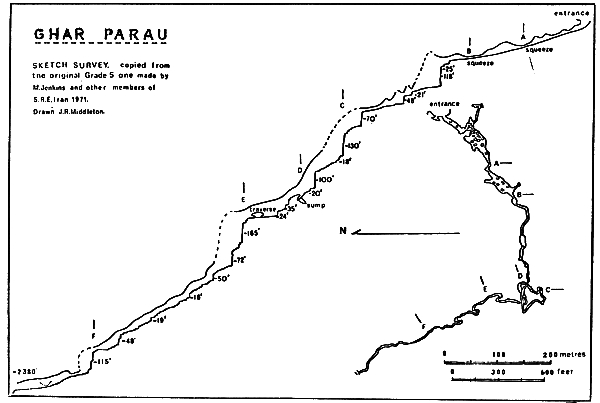

M. Ghar Parau (Parau Pot). As the largest of all the sinks on the plateau this cave is at the end of three dry stream beds which converge just before cascading over several large blocks of red chert into the entrance. In the stream bed at this point are several deep holes covered with flat rocks which are used as a water supply source after the streams have dried up by hunters and shepherds. Unfortunately there was none there during our camp. Once inside the six ft. high entrance arch, a series of steeply dipping boulder strewn chambers lead to an extremely chaotic section. Through here the same route was rarely followed twice, the only obvious pointer being a 15 ft. high mud covered boulder which had to be negotiated each time.

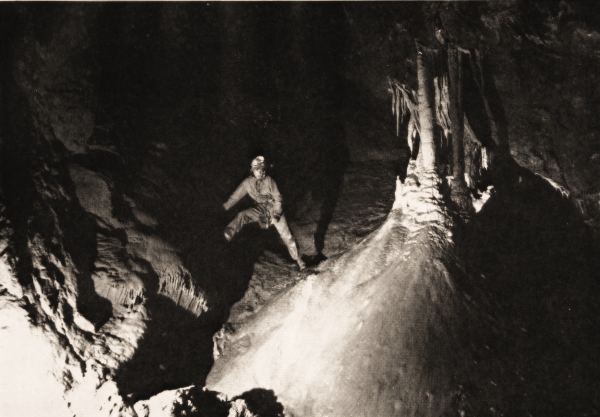

Shortly afterwards a more solid passage begins to develop only to close down suddenly to a three ft. wide by one ft. high crawl (A). Once through, the rewards are impressive as the continuation is a passage up to 40 ft. in diameter passing glistening calcite flows and grottos, over hard mud floors and down rocky cascades. In this section a large inlet enters containing several deep crystal clear pools from which fresh water was laboriously fetched for the camp each day.

Such beauty could only be short lived and round the next corner a head-first vertical slot twists into a horizontal squeeze (B). Several rocks had to be removed before further progress could be made .

On the other side of this constriction the cave presented us with a completely different face. From a gently sloping, roughly circular passage it now develops into a high rift, steeply descending numerous pitches and cascades in rapid succession. The cave is immensely solid with large Aventype chambers at the bottom of every shaft and high narrow twisting passages leading off which frequently need sideways movement. This latter is made more awkward by the many smaller steps up to ten ft. deep with chilly pools as landing places.

At the 1,000 ft. level (D) a small trickle of water, which has gradually developed, sumps in a constricted section but a way on was found by retreating for 100 ft. and then chimneying up into an abandoned and very greasy passage. This rejoins the trickle some 40 ft. lower down and 100 ft. further on. After two more pitches the stream again sumps, this time after a very jagged and sharp hands and knees crawl. Again a way on was found by going back and traversing upwards for nearly 50 ft. into a dazzling fairyland of virgin formations and needle sharp helictites. An airy but jug-handled descent is made at the end into a chamber with mud and gravel finely layered into a cross section nearly eight ft. thick. Several more cascades lead to the largest pitch yet found, a magnificent 165 ft. (E). This was the lowest point which I reached but on the last day an extremely fit team consisting of Glyn Edwards, Peter Standing and Mike Jenkins pushed on down a similar passageway for a further 1,000 ft. of depth in an epic 26 hour trip. They were stopped on the edge of a drop for which no more tackle was left.

Such success in so short a time (just five trips down the cave) can be attributed to just two things; the first was the marvellous team work and the second the abseiling and prussiking techniques which were used solely from the 900 ft. level downwards. The total depth we reached was 2,383 ft. with a length of passage just under one mile. The majority of the survey is to C.R.G. Grade 5c but the one reproduced in this Journal is in a condensed sketch form.

Return And Postscript

Our homeward journey we varied as much as possible and spread over fourteen days. We started by visiting the remainder of the mountain range to the west, finding it as promising as Parau. There proved to be even larger resurgences and we had some excitement when we were all rounded up one dark night by Kurdish soldiers who suspected us of being Iraqui infiltrators. Luckily, after being taken to their hill-top fort, we found that the commanding officer spoke a little English so after just one night ‘under guard” we continued our journey.

Through Turkey we travelled along the dismal and well-named Black Sea where we felt rain for the first time in five weeks. After Instanbul we kept south, crossed Greece and journeyed up the Yugoslav coast for its full 600 miles. From there it was straighforward across Italy, Austria and so back to the Autobahns.

The autumn of 1972 will see a further expedition to Ghar Parau which should have returned just before this report is published, but too late to be included. However it is hoped that if a new depth record is not reached at least the 3,000 ft. level will be passed.

Members of the Speleological Reconnaissance Expedition Iran 1971

| Glyn Edwards | Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club |

| John Harper | Wolverhampton Cave Club |

| Christine Jenkins | Food Officer. Wolverhampton Cave Club |

| Mike Jenkins | Wolverhampton Cave Club |

| David Judson | Deputy Leader. Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club |

| Peter Kaye | Cave Diving Group |

| Harvey Lomas | British Speleological Association |

| David Land | South African Speleological Association |

| Janet Middleton | Food Officer |

| John Middleton | Leader. Yorkshire Ramblers’ Club |

| Peter Standing | Doctor. University of Bristol Speleological Society |

Acknowledgments

Our sincerest thanks for invaluable assistance must be extended to the Governor General of Kermanshahan Province, to Mr. E. Abrahimy, the Director of Radio and Information, to Mr. Adelpour, his liaison officer and the local Highway Policemen. In this country Mr. A. M. Shapurian, the Press Attache at the Imperial Iranian Embassy worked extremely hard on our behalf and Mr. Norman Falcon, ex of B.P., gave us considerable practical information on the area. And last but not least our thanks to> the lady members of our expedition, Christine and Janet, without whose charm at the borders, patience at meal times and resilience to hardship, it is doubtful if we should ever have made it…

Some Useful Notes And Logistics Taken From The Expedition

by J. R. Middleton

General

The length of the journey from Calais to Kermanshah proved to be 3,880 miles. With non-stop driving to Istanbul and thereafter stopping each night it took us just 6\ days. With the exception of a 70 mile stretch of very badly corrugated dirt road around Myandoab in Iran the roads are surprisingly good. We had no problems with customs either way but at the Iran/Turkey crossing there was a good hour’s paper work. A visa for each person entering Iran is required and must be obtained in England. An individual transit visa is also needed for Bulgaria but this can be obtained at the border.

Transport

It is necessary to obtain a Carnet de Passage from the A.A. before taking a vehicle into Iran. The normal Green Card Insurance is valid in all countries with the exception of Bulgaria and Iran where good comprehensive cover can easily be arranged at the border.

Short Wheelbase Land Rover. The total mileage covered was 9,980 at an average of 18 miles per gallon. The only maintenance required was for one puncture, two oil changes, one new oil filter, four new light bulbs, one new speedo’ cable and a new wing mirror. The usual load was three persons (rather cramped) plus 800 lbs. Extras which proved very useful were free-wheeling hubs, and extra ten-gallon perol tank and a tropical roof.

Commer 30 cwt. Walk Thru Van. The total mileage covered was 8,050 at an average of 13 miles per gallon. The only maintenance required was five oil changes, two new oil filters, five light bulbs and one puncture repair. The usual load was eight persons plus 1,800 lbs. The dividing partition was removed and a three man seat added, two hammocks were also slung across and proved very useful.

Food And Cooking

We had approximately 25% of our food donated by firms and the remainder was purchased, usually at advantageous prices. Of what we took about 40% was dehydrated, 40% was tinned and the remainder we purchased locally. Meat and sweet things proved to be the most important items and those most in demand as fresh meat rarely looks trustworthy and anything sweet is almost unobtainable.

Whilst travelling we cooked breakfasts but purchased our evening meals and found this an ideal solution so that the vehicles were not disrupted too much. Once in camp we cooked breakfasts and evening meals and took dry snacks on our explorations. For the first week we all drank vast quantities of fluids and the three gallons of concentrated cordials we took soon ran out.

For cooking we used petrol stoves but found them, once encamped, unsatisfactory for such hot and dusty conditions. Gas or paraffin are probably better.

Equipment

As we were primarily a reconnaissance expedition we only took the minimum of gear but in the event used it all. Items which we found of particular use were bolts (for placing belays), pegs (for climbing and where cracks were available for easier belays), gloves (for abseiling and avoiding cuts), and good quality nylon rope (the cheaper tended to twist badly when abseiling).

We took and used: —

1,000 ft. 1½” polypropylene rope

600 ft. 1¼” cheap nylon rope (hawser laid)

300 ft. 1¼” good nylon rope (hawser laid)

1,000 ft. wire ladder

30 bolts

25 pegs

56 lb. carbide

Surveying was done with Suunto Compasses and Clinometers plus fibron tapes.

Financial

To say that the only item we received free was about £50 worth of food the expedition was a surprisingly low cost one as can be seen from the balance sheet.

|

|