{C2 word 1 and 2#then words 4 to 106}

The Reseau Felix Trombe

by J. R. Middleton

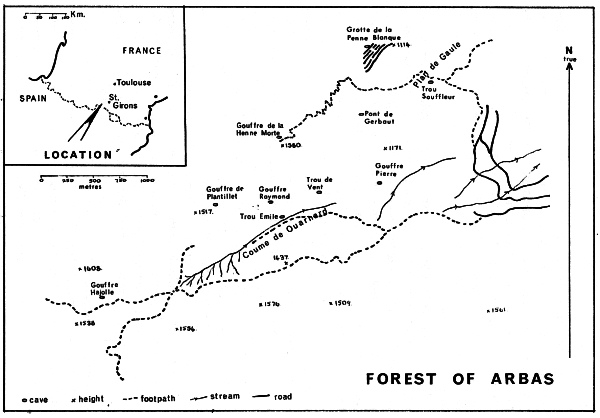

The longest and perhaps most complex cave system in France is situated in the Pyrenees beneath the many-coloured trees of the “Forest of Arbas”. A dense tangle of birch, beech and conifer rises to a height of over 1,500 metres above the slumbering village whose name the forest bears. On the lower slopes a thick carpet of leaf mould, fallen trees and brambles helps to camouflage numerous cave openings whilst higher up, as the trees start to thin out, the holes appear amongst a more typical limestone surround of clints and depressions. Further up still, even to the summits, heathers and wind-blown junipers crowd to the edges of Yorkshire-type shakeholes.

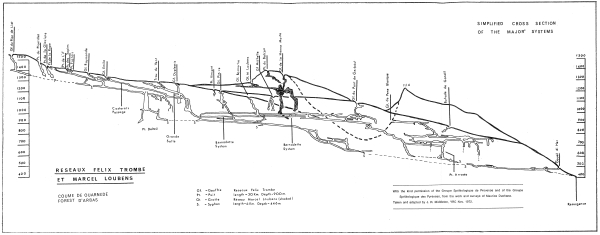

The Reseau Felix Trombe is not just one deep cave, it is to date, a series of ten inter-connected major systems. Its total depth from the highest entrance, Puits de L’If, to its terminal syphon is 900 metres, making it the fourth deepest in the world, and its combined length is in excess of a surveyed 30 kilometres. Its potential length is considerably more, as apart from possible other connections with caves in the area, it is assumed to connect with the 6 kilometres long Reseau Marcel Loubens which includes Casteret’s “Gouffre de la Henne Morte”. As to depth, the terminal syphon is almost 70 metres above the resurgence and the highest known and as yet un-connected cave is over 100 metres above the Puits de L’If.

Towards the end of October 1972, Clive Rowlands and I were privileged to visit this complex as guests of the Claude Chabert of the “Speleo Club de Paris”. A recent extension had joined the Grotte de la Pene Blanque to the Reseau Felix Trombe deepening the whole system considerably. Our object was to make and prove possible a first through trip from the Gouffre Emile, high in the mountain, to Pene Blanque which is the lowest entrance. This traverse we most successfully completed in an unbelievably exciting 28-hour trip. We descended to a depth of nearly 720 metres and then climbed out over 200 more. In between we covered 8 kilometres, made 20 abseils, did two Tyrolean traverses, waded for over an hour in waist deep water, passed through every type of passage imaginable and used every technique both known and unknown to us.

The Traverse

The quivering flames licked at the grey stones as they reached towards the blackened chimney. The pinewood logs crackled and spat upon the open hearth. We sat around the survey strewn table, Claude, his fiancee, Nicki, and Bruno Dressier, all from Paris, then Maurice Duchene and his fellow cavers from the Groupe Speleologique des Pyrenees and us, the two English already wondering what we had let ourselves in for.

That night we made our plans. There would be eleven of us. We would split into three teams, and enter the system at two hour intervals. It seemed a large party but it was obviously necessary as no single member knew the complete route, only certain sections, so it was intended that by using combined experience and “Scotch Light” tape a way would be forced. Clive and I hoped so, as an abseil down the wrong way would mean a long and cold wait … The first team of four would place markers, bolt pitches if necessary and take in a long rope for the big 90 metre abseil. The second party of three would follow, helping the first if they caught up, and then waiting in Pene Blanque to assist the third team out. The whole trip was expected to take around 18 hours and it should not be too wet. It sounded simple, straightforward and obviously well organised. Clive and I slept soundly.

The Gouffre Emile is perhaps the easiest of all entrances to find as all it is necessary to do is to follow the path at the end of the road over a ridge and into a valley, follow this up until a stream is reached and the trees start to thin out. By the side of the stream and only one hour’s walk from the road was the entrance, barely a metre in diameter and starting with a short vertical drop into a small chamber. A superb high and narrow streamway meandered away between numerous cascades of yellow calcite and over floors with crystal clear pools edged in flowstone. Two pitches followed, one of 5 metres and one of 7, and here again we felt apprehension that the trip might not be quite what we expected. Bernard, who was leading in this section, immediately bridged his way down the slightly overhanging pitches on minute nodules of calcite. We followed.

The passage continued in this sporting vein down numerous cascades and a further pitch of 10 metres, then the whole system suddenly changed character. The roof came down, the walls widened and became coated with mud until the inevitable sump arrived. Just back a short distance we scrambled round some boulders and entered a dug out crawl leading to a difficult 15 metre climb up a slippery wall. At the top a narrow twisting rift led us into the side of the “Grand Salle” of the Trou du Vent: a main passage almost as large as Gaping Gill but vanishing into the distance. The second team caught the first up here so a stop was made for food and to marvel at nature’s work.

The French had used this chamber to camp in and had discovered the Gouffre Emile after a considerable amount of work. Exploration was then made slowly upstream until the small chamber just below the surface was reached. This entrance was then opened up and a new way in found.

The first party left and when we were too cold to wait any longer we set off to the end of this impressive gallery, over a slab, down a boulder and into a beautifully waterworn cascade passage terminating all too soon in a free-hanging 25 metre pitch. More sporting going followed with traverses around deep black holes, crawls through tubes, a climb down a steep wall and finally a walk to the edge of a deep cross rift over which the water roared and frothed We just caught up the last members of the other party who* had been experiencing trouble when abseiling down without a long enough rope, consequently two had been joined together and this necessitated getting off on a small ledge halfway down the 30 metre pitch, passing the knot and then continuing. The pitch proved extremely wet and from a small ledge just before the bottom we made a short climb to a window, at the other side of which was the big 90 metre shaft. Bolts had been put in at the top and a ledge broke the descent at 25 metres, the final section proved really magnificent as at least 50 metres of it hung free into a large passage.

The cave now seemed to take on a much sinister and serious air as apart from getting noticeably harder technically we saw no more formations and the surrounding limestone was much darker. An hour of hard going saw us at the head of a seven metre pitch where we left the not inconsiderable stream and made a difficult climb up into the incredible fossil galleries of the Reseaux Bernadette.

The Reseaux Benadette is a very complex series of large abandoned passageways totalling many kilometres which have not yet been fully explored. They join the Trou du Vent to the Gouffre de Pont de Gerbaut with the Gouffre Barnache also entering. The galleries which we traversed were so dry that a small kick at the fine silvery sand caused a cloud of dust to rise. We followed the main way for nearly two kilometres of easy and relatively flat going to large chamber with a small trickle of water falling from its roof. This was, in fact, the only water we saw in the whole series. We had now caught up with the others again and were amazed to learn that we had already been down for over twelve hours and had still not reached the half way point. Dejected we sat down for a second snack and a well earned rest, the stenuous sections of the river passages and now the monotony of these big dry galleries beginning to take their toll.

Just before we all started to nod off, Jacques, the leader of the first team managed to rouse us back into action and led us away from the main passage and into a narrower one with a weird erratic stalactite hanging just inside its entrance. The going was proving more strenuous now with awkward climbs over and through superbly waterworn projections and difficult traverses round deep holes. After one very awkward one a large 30 metre deep and 10 metre wide shaft completely blocked the way. Any drowsiness we may have felt left us as we watched Jacques crab onto the line stretched across the void, slide speedily down to the middle and then pull himself up the other side. We followed. With the extra adrenalin now coursing through our veins we again took greater interest in where we were going. The passage enlarged until it was well in excess of its original size and “Gaping Gills” were the order of things, each separated by large piles of scree and rock which we repetitatively climbed and descended. At the bottom of one of these chambers a small squeeze led us from the Bernadette system and down through a complicated choke for 40 metres back to the stream. The icy water really woke us and we made good speed for over 400 metres passing many sporting cascades and fine formations until we reached the head of a 60 metre pitch. Just before descending this obviously very wet way we noticed the first team vanishing from sight over the top. Up we followed and into an amazing mini-network of descending and inter-connecting tubes and rifts eventually landing back in the stream via three pitches of six, five and twenty-five metres.

The next section of our explorations confirmed our earlier vague suspicions that “the cave might have more to it than we thought”. Undoubtedly the most arduous part so far followed, since for over a kilometre we waded in the chilling water which was never less than waist deep, frequently up to our necks and occasionally even over our heads … (Someone had said that it would not be too wet so we only wore long Johns, pullovers and boiler suits). The floor, which for the most part we could not see was covered with incredibly slippy flowstone, the force of water literally shot us over cascade after cascade as well as seven more pitches. This section finished with a truly beautiful 28 metre abseil by the stream into a shallow lake in a large chamber.

At the far side hung salvation in the form of a 35 metre ladder leading up into the Pene Blanque system. Several of the Pyrenees Group had put this in the day before we entered. Our battered bodies had now been going for 22 hours and in the draughty chamber at the top of the pitch we decided that due to our state and length of time below we would all go out and apologise later to the third party—of whom we had not yet seen any sign. The way on was thankfully dry and after passing a squeeze and descending a small pitch we reached the second of the Tyroleans. This time not quite so awe-inspiring but still exciting with its shower of water half-way across. The pitch below was the way to the deepest part of the Reseau Felix Trombe at—900 metres, still over 160 metres below us.

From now on Claude knew the way as he had taken part in pushing the exploration of Pene Blanque some nine years earlier. We followed him through large boulder and chamber complexes, clambered up steep slopes and then back down again, climbed a thirty metre wall and then, at last, seemed to travel more up than down. In the absolute dryness our English type Carbide lamps had long gone out and we blindly clung to the others’ shadows. Gradually the passage became smaller and more interesting with many sporting climbs and traverses until we finally reached the place where Martel had stopped on his inward exploration. Once past, a solid mud floored passage one to one and a half metres high and six metres wide led us round several bends to what must be one of the most impressive exits anywhere. For the last 50 metres we had a gradually enlarging view through autumn-tinted leaves over the vast plains heading towards Toulouse. We again breathed the sparkling mountain air for the first time in 28 hours.

The third party surfaced some seven hours later, having been lost in the Reseaux Bernadette for four hours trying to find the way through the boulders and back down to the stream…

In finishing we must thank Claude Chabert for giving us the opportunity to take part in this unique first traverse which must surely now dwarf even the mighty Trou de Glaz and Pierre St Martin classic through-trips. Our thanks are also extended to Claude, to Nikki and to Bruno for their generous hospitality and friendship and of course to the cavers of the Groupe Speleologique des Pyrenees without whom the trip could never have been made.

Resume Of The Main Explorations

Grotte de la Pene Blanque. alt. 925 m.

1908 to 60 m. Martel.

1952 to — 110 m. Speleo Club de Paris.

1953 to — 260 m. „ „ „ „

1955 to — 305 m. „ „ „

1956 to — 360 m. „ „ „ „ To the Puits des Paques

1963 to — 380 m. „ „ „ „ To the Puits Arroses

1963 to — 380 m. „ „ „ „ Ended in a sump

1971 The Groupe Speleologique de Provence and the Groupe Speteologique des Pyrenees discovered a passage above the Puits Arroses and made the connection with the Pont de Gerbaut.

Gouffre Pierre, alt. 1131 m.

Discovered in 1956 by Pierre Gicquel.

1956 to — 150 m. Guy Maurel.

1957 to — 320 m. Groupe Speleologique de Provence, 2nd Aix en Provence.

1958 to — 564 m. Groupe Speleologique de Provence, and Casteret. Terminated in the Syphon du Fer.

Gouffre Raymond, alt 1,275 m.

Discovered in 1957 by Norbert Casteret.

1957 to — 195 m. Groupe Speleologique de Provence, 2nd Aix en Provence and Casteret. They reached the top of the Puits Delteil, later proved to be 130 m. deep, free hanging all the way and wet.

1959 to — 448 m. Groupe Speleologique de Provence, 2nd Aix en Provence and Casteret.

1959 to — 492 m. Groupe Speleologique de Provence, 2nd Aix en Provence and Casteret.

Terminated in a sump. Made a first connection with Puits de l’If.

Trou du Vent. alt. 1,236 m.

Discovered in 1956 by Norbert Casteret.

1956 to — 75 m. Groupe Speleologique de Provence, 2nd Aix en Provence and Casteret.

1958 to — 200 m. Groupe Speleologique de Provence, 2hd Aix en Provence and Casteret.

1960 to — 300 m. Groupe Speleologique de Provence, 2nd Aix en Provence and Oasteret.

Stopped at the top of a 94 m. pitch.

1960 to — 657 m. Groupe Speleologique de Provence, 2nd Aix en Provence and Casteret.

Made a first connection with the Gouffre Pierre.

1962 to — 713 m. Jolfre, Lefranque and Felix. They also climbed an inlet which is now known as the Gouffre Emile and is a further entrance.

1963 to — 765 m. 2nd Aix en Provence and Casteret. A first connection was made with the Trou Mile at — 100 m. Discovery and exploration of the Reseau Bernadette commenced. First connection with Pont de Gerbaut made.

1964 to — 811 m. Jolfre, Lefranque and Nave. First connection made with Gouffre Raymond.

Pont de Gerbaut. alt. 1,181 m.

1908 Discovered by Martel and explored to first pitch which was considered too dangerous because of loose rocks.

1936 to — 100 m. R. de Joly and Casteret.

1963 to — 130 m. Jolfre, Lefranque and Nave after digging.

1964 to — 186 m. Jolfre, Lefranque and Nave after explosives. First connection made with Trou du Vent.

1964 — 370 m. Jolfre, Lefranque and Nave and Cordee Speleologique du Languedoc.

1964 to — 480 m. Jolfre, Lefranque and Nave.

First major traverses

1965 July From Puits de L’If to Pont de Gerbaut.

1972 July From Puits de L’If to Pene Blanque (without touching the Trou du Vent system).

1972 October From Gouffre Emile to Pene Blanque (through the Trou du Vent system).

I am indebted to Claude Chabert of the Speleo Club de Paris for supplying all the above information.