The Los Tayos Expedition

(or Close Encounters of the Ecuadorian Kind)

by J. C. Whalley

If there is an epicentre, or wellhead, of British caving endeavour overseas, then surely the Craven Heifer at Ingleton could lay strong claim to fulfilling such a role. Many an expedition has been conceived on the back of a cigarette packet within the overcrowded austerity of its public bar. Certainly our involvement in the Los Tayos affair, itself a Scottish/ Ecuadorian venture, stemmed from a chance meeting there between David Judson and John Frankland, the CRO doctor, one Saturday evening in 1976. John spoke of being invited on an expedition to South America.

The picture emerged of a huge undertaking of soldiers and scientists being airlifted to a remote Amazon Headwater location in order to descend a deep shaft. Apart from John Frank-land and Jim Campbell of the Grampian Speleological Society, both of whom would be committed to scientific duties, the only caver was Pete Holden of the Army and so, with only seven weeks to departure, the feeling developed that a few other cavers might be useful. Dave promptly telephoned the expedition leader, Major Chris Browne, with the offer to form a caving team. This was accepted, the team comprising Judson and myself with Arthur Champion of C.P.C., Dave Checkling of L.U.S.S., and Pete Cardy and John Harvey of S.W.C.C. None of us knew much about Ecuador, least of all its whereabouts, but we did have certain pertinent skills and a hunger for adventure in far-away places so we jumped at the chance.

A briefing meeting was held at Redford Barracks near Edinburgh. Our objective was Cuevas de Los Tayos, the “cave of the oil-birds.” The entrance shaft had been descended on a previous occasion although there appeared to have been little lateral exploration. We were shown slides taken of other slides projected onto the floral wallpaper of a Quito hotel, so the quality left something to be desired. The cave was situated by the Rio Santiago in the Cordillera del Condor, where the first foothills of the Andes rise above the Amazon Basin. The locals are the Jivaro Indians who acquired a reputation during their head-hunting past and managed to expel both Inca and Spaniard in their turn.

The scientists on the expedition were mainly zoologists and botanists, over twenty in number with an equivalent contingent of Ecuadorians. The job of getting them there was undertaken by the army who, no doubt, viewed the exercise as a valuable opportunity for jungle training. There were various other individuals: a village constable, a peer of the realm, the “Nurse-of-the-Year,” a film crew, an expert in thermo-lumines-cent dating and, as President, none other than the first man to step onto the moon, Professor Neil Armstrong.

Professor Armstrong had been invited to be the expedition’s figurehead, partly because his ancestral roots lay in Dollar, Clackmannanshire, which was the home of Stanley Hall, the amateur archaeologist who first mooted the expedition. Hall himself emerged as a somewhat enigmatic figure and when we listened to him it became clear that, however sound and prosaic were the various motives of the rest of the expedition, he personally was drawn to Los Tayos for wilder, more eccentric reasons. It transpired that a number of quite fantastic claims had been made for the cave by various people including Erich von Daniken. In his book, Gold of the Gods, he asserted that the caves were artificial, stretched the whole length of the Andes and were made by a race (probably extra-terrestrial) who had thermic lances and nuclear weapons. Of course, as we could see from the photographs, there could be other interpretations : the “molten rock” could be merely flowstone and the “gigantic masonry” the joint-pattern to be expected in limestone. In fact there were several other points in the book which were open to question. Nevertheless it was a sensitive area. Certainly Hall was still looking for a major archaeological revelation and yet to be associated with the Daniken account would make a laughing stock out of the expedition.

There was a further meeting, in London: a cocktail party for the purpose of cajoling financial backing from big business and then, for the remaining week, we were on tenterhooks as the expedition’s viability lay in the balance.

The day arrived. After a long day at Heathrow Airport, relieved only by a ferocious bout of eleventh-hour innoculations, we were in the air, riding a Jumbo westwards. Breakfast stop was at Call, Colombia, which I am told, has the world’s most beautiful women (and more than its share of muggers and pickpockets). We only saw the airport. Memorable were the humidity, the lyre-birds, the hazy, incredibly high horizon of the Andes and several huge beetles and locusts crawling purposefully across the concrete. I shuddered inwardly, wondering what the jungle had in store for us.

Quito, the capital of Ecuador, immediately impressed us. Situated high in the Andes it is nevertheless dominated by volcanoes, particularly Cotopaxi and Antisana. Our stay was a brief one; 24 hours split between a diplomatic garden party and our accommodation in an Ecuadorian Barracks.

Ecuador has three regions. Quito is situated in the Andes and their associated intermontane valleys. Despite its location on the equator (Spanish: el ecuador), this region is cool due to its elevation. On either side the Andes fall away to tropical jungle regions: the coastal one has a climate tempered by the cool Humboldt current. Our objective, however, lay in the Oriente, the jungle region to the East. The contrast between the dry exhilarating mountain air of Quito and the hot, heavy humidity of the Oriente was total.

Most of us travelled by bus to our base at Pastasa near Puyo. The scenery we passed through was extremely impressive, particularly the Mera gorge. The journey was not without event, the driver being somewhat cavalier. He was especially good at reversing into lamp-posts and upsetting banana stalls. At one point the road was blocked by landslide, apparently a frequent occurrence.

At Pastasa little time was lost in packing men and equipment into Aravas (short-take off aircraft of Israeli manufacture) for the next stage of our journey deep into the roadless jungles. Our aircraft droned alarmingly under its payload but we were rewarded by a superb view of Sangay soaring above cumulus clouds and deceptively tranquil. (It was to vent its anger on another British party shortly afterwards). Looking to the green carpet far below we could see the small clearings and huts of the Jivaros and finally we caught sight of the Rio Santiago meandering towards the Atlantic through the eternal jungle.

Santiago base, Teniente Ortiz, gave us our first taste of the jungle and of the incessant polyphony of the insect legions. Despite its great width the Rio Santiago had a very swift flow and it was obvious that we would need the army inflatables to make headway upstream. After several attempts, one of which resulted in the indignity of being rescued by a dugout canoe, a reconnaissance party forced its way through rapids to the Coangas tributary to reach the cave site.

A huge airlift followed as soon as helicopters could be spared from their normal flood-relief duties. The destination was a ridge consisting of three platforms. This was substantially cleared of trees and afforded excellent views across the jungle to the thickly vegetated cliff-scarred hills of the Cordillera del Condor. There was a water hole nearby fed by an active stream and this was ideal for washing and bathing, as well as a supply of fresh water. The cave was reached by a steep muddy track. If one imagines Gaping Gill overgrown with jungle one has a very accurate picture of the entrance to Los Tayos.

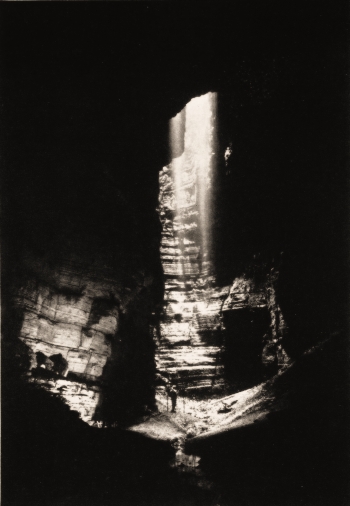

The first descent was made by Judson and Champion virtually as soon as the “chopper” had landed. They found the entrance to be a vertical shaft of about 150 feet, with the weird noise of the oil-birds echoing up the shaft like manic laughter. The remains of a vine ladder was in place and this they cut down. The local Indians climb these free-hanging pitches on ships’ ladders of stakes and twisted lianas, or shin down poles on shorter pitches, in order to harvest the oil-birds (Spanish: los tayos). The oil-bird is a fairly large, handsome bird which occupies an equivalent ecological niche to the bat. They emerge from the cave each evening (someone said always at 9 p.m!) to forage for palm nuts etc. which they store in their nesting places in the cave roof. They emit a series of audible clicks in order to navigate underground.

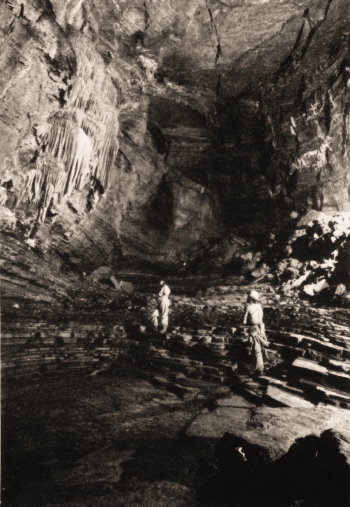

The entrance series led to an impressive square-section passage and then came a huge indeterminate chamber of highly complex topography. From the bottom of this smaller passages led to the sump while a lateral route led to a streamway and the Amphitheatre, an extremely impressive chamber, the floor of which gave rise to its name. Arthur and David did well to explore all the above on that first trip, but it was a disappointment to reach the sump so soon and those of us who had been cutting wood, erecting tents, etc., were a little chagrined.

This was alleviated by the discovery of Commando Cave by Cardy and Dr. Jefferson. Work now concentrated on rigging a gantry and winch on the main shaft but sufficient resources could be spared for trips into this new cave. In essence it was rather like a Yorkshire pothole with classic vadose fissure-passages and interconnecting pitches. The fauna was different of course and on my first trip we encountered tail-less whip scorpions, bats and freshwater crabs. The cave ended as a pitch into the Los Tayos Amphitheatre. Another branch, Shovell Pot, was explored as far as possible and provided a very wet trip.

The cave exploration in the main cave developed mainly into following inlets, some of which provided great sport, from the Amphitheatre region. It seemed that one could go on indefinitely finding lateral connections into parallel stream-ways. A major find was M6 series with its awesome stalagmite near the far end. This formation alone compensated for the general dearth of formations in the system.

Downward exploration was halted by the sump which was about 600 feet below the entrance and at the expected saturation level relative to the Rio Coangas.

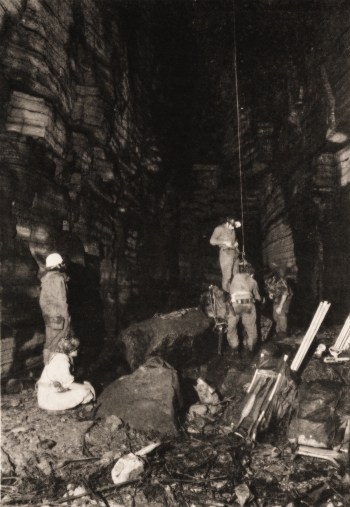

During the course of the expedition the cave was visited by virtually all the scientists and soldiers. The safe handling of this traffic was the caving team’s primary function and, to this end, an electric window-cleaner’s hoist was used as a winch capable of lifting two persons. I remember the time when I was on gantry duty for the first time and secured a diminutive Ecuadorian geologist into the bosun’s chair. He was lowered a few inches to enable me to clip his colleague, an enormous rotund man who had been fitted out with a Whillans harness, into the eyelet above the bosun’s chair. It was a very comical sight: the big man was obviously quite beside himself with fear, and neither of them had any English. After what seemed like an eternal moment I pushed his feet off the planks and signalled “Down.”

The quality of life in camp was governed completely by the weather. It rained rather more often than not, and the large number of people in camp quickly turned the ground into a quagmire. Much of the soldiers’ time was spent cutting wood to create duck-board walkways. When the sun did shine through there was barely time for the mud to dry into a stiff paste and then the rains would come again.

We had many visits from the local Indians who did a roaring trade in ironwood spears, blowguns and tooth necklaces. It must be said that the quality of the products deteriorated as the Jivaros tried to keep pace with the demand. They lived in bamboo-and-thatch huts in garden clearings, pursuing a “slash-and-burn” agricultural policy. They provided a lot of our food, including a pig which kept the camp going for three days. One of their specialities was manioc beer which starts out as a tuber chewed by the old women and ends up tasting like a mildly alcoholic buttermilk which provides the staple liquid intake of the Jivaro. If any remained long enough to reach maturity, according to one authority, they had an excuse for a big celebration which was the reason for the spacious huts.

The Indians were great collectors of our refuse. Discarded tin cans, even the bosun’s chair, when we had finished with it, were eagerly salvaged and, no doubt, put to effective use. The expedition doctors were kept busy attending to their minor complaints and full advantage was taken of the Ecuadorian military presence in settling their various feuds and disputes.

Wildlife was legion of course and provided an endless source of specimens for the scientists and fascination for the rest of us. One of the images staying with me is of Colour Sergeant Orr charging across the base camp landing strip with a huge butterfly net. He collected nearly a thousand different types (not all at once though!)

Practically all the life in the caves consisted of either surface species which had “dropped-in” and adapted or had simply “dropped-in.” Notable in the latter category was a python and several bootlace-type snakes encountered near the entrance.

Further into the cave were the rats. We could hear their squeals and see pairs of pink eyes darting furtively from boulder to boulder. Their prey was the defenceless young oil-birds. Not yet able to fly, the fledglings could be dislodged from their precarious perches in the roof.

Beyond this zone one entered the domain of the tarantula; the giant hairy spiders or mygalamorphs. One of these, which was brought out to study and then released, had an abdomen the size of a duck-egg and weighed in at half a pound.

Particularly interesting were the beds of etiolated seedlings encountered throughout the cave. These developed from palm-nuts etc. dropped by the birds into guano-banks where they germinated and grew to a height of up to a metre, reaching towards a sun they would never know. The beds were quite dense and gave refuge to the occasional giant transparent cockroach, and other sundry delectabilities.

Towards the end of the expedition a major archaeological find was made in a small passage at the foot of the second daylight shaft. Various shards of pottery and seashells were unearthed and estimated to be thousands of years old by the resident archaeologist, Padre Porras.

Neil Armstrong was flown in to Santiago base after the cave had been de-rigged. Consequently the cavers stood by with ladders and rope (the latter 1,000 ft. of “Bluewater” prusiking rope, had in fact been donated by Professor Armstrong). As soon as he could be separated from his entourage of V.I.Ps. and autograph hunters we were whisked up to the cave site which was by then only occupied by Major Browne and a small party who were out of radio contact and knew nothing of this development.

We had to work quickly to ladder the shaft and be on our way down before the next helicopter arrived and the ground became thick with generals, embassy staff, military attaches, newsmen etc. In the event Pete Holden and I were privileged to accompany Neil down to the sump. Neil is a quiet man and gave us an impression of not being one for small talk, rather he had an air of being capable, observant and self-possessed. As may be imagined he took the trip in his stride. From the sump we elected to go out a different way which neither Pete nor I had been along before but which we knew in theory would bring us into Stanley Hall, the big chamber. Having to crawl over a dead oil bird was not too good a start but when we became faced with a row of climbs up dodgy boulders with no indication of which was the right way, we became anxious not to lose Neil’s confidence (at least I was, Pete is never anxious and kept up a constant stream of irreverent wit). By either luck or intuition we did select the right climb however and emerged into the hall below a superb stalagmite. We set off at a cracking pace so as not to miss the last helicopter. Pete warned Neil that he may find us a little possessive as he constituted our insurance for the airlift. It was a superb line up the shaft: John Frankland had organised a team of squaddies into the best lifelining team I’ve come across. The helicopters had gone so with our bedding at base camp, we were faced with a cold night in the camp. However, there was a large fire which we sat around on logs in the still evening air, roasting potatoes and drinking firewater. The moon was out overhead when we listened to Neil talking about his voyage there in the Apollo spacecraft. Major Real made a long emotional speech which kept branching off along philosophical tangents to such an extent that we feared he would never be able to finish.

It was quite an evening. There was a week left for us to see a little of the rest of Ecuador, and for Arthur Champion and Dave Checkley to piece together the survey on which they and D. M. Judson had worked so hard in the cave; and yet surely that evening round the fire, with the forest stretching all about us, was the true and fitting conclusion to our adventure.