Y.R.C. Reflections

by the late Geoffrey S. Gowing, edited by Richard Gowing

One of my pleasantest relaxations during the late twenties, the thirties and the immediate postwar years was my association with the Y.R.C. With them I got to know a wide variety of pleasant companions in whose company I spent many happy days on fells, rocks and in caves.

My first introduction to rock-climbing was by Basil Goodfellow in 1925. In the late summer he and I went over to the Lake District in his polished aluminium two-seater Alvis one Saturday and stayed with the Peppers, in Seatoller. Around tea-time we strolled up towards Tarn-at-Leaves and came in the gathering darkness down the steep valley side to Seathwaite. On the Sunday we did a rock climb, Eagle’s Nest Arete behind Napes Needle.

From then onwards I spent many happy weekends in the Lakes, sometimes staying in Seatoller, but more often at Burnthwaite or The Wasdale Head Hotel, with either Basil, or Rummy Sale, who was to be my Best Man in 1929.

And so to the Y.R.C. In 1927, when I.C.I, started doing research into the production of oil from coal by the Bergius process, they took onto the staff a chemist called Alexander Rule. Rule had been a lecturer in Chemistry at Liverpool University and was an expert in that process. (He lived in Norton until his death in 1957, and proposed my son, Richard, in turn for membership of the Club.) Rule had for many years been a member of the Y.R.C. and in the summer of 1928 he invited Rummy Sale and myself to a meet at Gaping Gill. We camped somewhere in Dentdale, joined the Club on the Sunday and duly went into the pot, on what was to be the first of many descents. As a result of this vetting, we were both duly approved and elected members of the Club, and in that late autumn, attended our first meet at The Rose and Crown in Wensleydale. Thereafter I must have missed few meets, with the exception of the two years I was in South Africa, until the outbreak of war in 1939. The Y.R.C. in those days had a fascinating membership, as there were several original members and a number who had joined in the first years of the Club’s life. The Club had taken some time to get into its stride again after the war and there were comparatively few young members – practically none in their early twenties. The membership consisted almost exclusively of West Riding men who ran their own businesses and whose sons were beginning to follow their fathers. There was, for example, old Tom Booth (an original member) and his two sons, who ran a flourishing business in the woollen trade. Then Davis Burrow, who was Secretary just after I joined, and his cousin Charlie, who were brush manufacturers. There were the Humphreys brothers, who ran a successful little electrical engineering business; when Albert, on his retirement, sold the factory to The General Electric Co., he made enough to keep himself and his niece Grace who kept house for him, in great style in Uppermill near Oldham until well into his nineties, spending most winters in Greece, the West Indies or South Africa. He died in 1979.

Then there were a few professional men – lawyers, like Harold Brodrick. He lived in Birkdale, the fashionable residential suburb of Southport, of which he was mayor when I first knew him. There was old Dr. Lovett, whose son is in the Club. The old man was the G.P. in Clapham and it was in a barn attached to his house in the village where we used to store most of the Club potholing tackle. Among others of the professional men there was, of course, Ernest Roberts who was a school-inspector, Davidson, who was a retired bank-manager – and Rimmer, who was manager of the Metropole, one of the large hotels in Leeds. Rimmer and I served together on the Committee in the year before and during the Second War and he always used to give me dinner in the Metropole Grill Room when I came over to Leeds to the meetings. On these occasions! often used to stay with Davis Burrow and his wife in their charming house in Alwoodley, right on the northern edge of Leeds, with a grand view over the countryside to the crags of Almscliff.

I can only remember one schoolmaster in the early days: this was Bentley Beetham, of early Everest fame, who taught for many years at Barnard Castle School. I met him several times in Borrowdale, where he used to bring over climbing parties of schoolboys and put them up in a hut he owned. This was a vast, corrugated-iron building which had originally belonged to the old Wad mining company. I remember running into him once when we were staying in Stonethwaite and he led Richard and me up a climb opposite the hut – Richard’s first rock-climb.

The President in the year I joined was H.H. Bellhouse, a retired bank-manager and an original member of the Club. The Secretaries were Jack Buckley, who ran a printing business in Leeds, and Fred Booth, son of old Tom. Old Tom died in the late thirties en route to visit his daughter Linda, in Switzerland; he was a grand old boy who, as a lad, had been a member of the crew of a sailing ship and had “rounded the Horn” under sail.

The twenties and thirties were great times in the Club. The January meet was always at the Hill Inn and was a great occasion, the dinner on the Saturday night being almost as important as the Annual Dinner – we even sometimes had a guest. I remember one such was the vicar of Chapel-le-Dale. He was a very old man, who had been one of the early climbers in the Alps – a fact that I fortunately learned just before we sat down, as it fell to my lot to propose his health after our meal. We generally put on some kind of entertainment in the evening, which took many forms. Once we had a treasure hunt, with clues that led us through the snow half-way up Ingleborough on the one hand and up Whernside on the other. The solitary clue that sticks in my mind was “Fill pints, but not with tea”, which led to the farmhouse, Philpin by name, near the Ribblehead Viaduct. On another occasion, someone brought in a portable radio set and switched on some loud music. Someone else, having been primed, said “Can’t that d— noise be turned off” whereupon to the utter surprise of the company, the music stopped and the loudspeaker blared forth in the unmistakable voice of the President of the Club, an admonition to the speaker himself to shut up, as they were about to broadcast a live transmission of a descent of Gaping Gill. Then followed an announcer telling us that the famous potholer Ernest Roberts was about to descend and we heard such typical comments as: “Let go, d— you. Blast you, hold tight. What the h— are you doing. Slack away, confound you!”, so well known to those who potholed with Roberts. Once the whole party was cajoled up the fellside to see “great illuminations in Douk Cave”, only to find that someone had left a solitary candle in the entrance.

On another occasion Charlie Burrow, disguised as a local policeman, took everyone in when he entered the pub and arrested the President for indecent exposure or some such offence. Then there was the time when we laddered right across the roof of the hotel, from ground to ground on each side, and the whole party, some thirty strong, tied up on one rope. The confusion can readily be imagined, particularly as two of us were able to lean out of a window and fasten the middle of the rope to one of the ladders! Latterly we quietened down and adopted a standard after-dinner exercise of climbing a rope ladder, stretched at 45+ to the horizontal in the big barn, up to a minute hole in the gable end, whence a vertical ladder led in the dark to the top of the dung heap outside!

The other great meet of the year was the camp at G.G. This was camping in the style of the early years of the century, with a marquee with tables and benches for messing and a bell-tent for cookhouse, complete with an elaborate paraffin cooker and oven. Over this presided Percy Robinson, a fine old member who had been an army cook during the war. With an assistant, another ex-army cook who had been Davis Burrow’s batman in 1914-18, he turned out the most superb food. Piles of sausages and bacon and eggs for breakfast, vast stacks of sandwiches to take below and always on the Saturday night an enormous joint of roast beef with real Yorkshire pudding – none of your miserable individual pies, but a vast spread cooked under the joint and soaked in the fat that dripped therefrom.

There was always a bell-tent pitched close to the windlass at the brink of the open pot; this housed the field telephone which was connected to a hand-set on the floor of the cavern and was presided over by “old” Harry Buckley, father of Jack Buckley. There they sat with the aid of a case of whisky, keeping a record of the descents and ascents of the pot, so that nobody should be left behind in the bowels of the earth.

Although exploration went on, the G.G. meets were generally recognised as being social affairs like the Annual Dinner, rather than serious potholing occasions. They were always preceded by a weekend at which a few stalwarts took the tackle up to the pot and got the winch and gantry into position. Generally Percy Robinson took his holiday and stayed there the week before and the week afterwards. Women, of course, were not permitted at the meet, but sometimes accompanied their husbands on the weekend before and, if there had been time to rig the tackle completely, I fancy a few were allowed down.

Other meets were held in the usual climbing, walking and potholing areas of the north, in the Lake District, the North York Moors, one or two in the Derbyshire caving district or in the Trough of Bowland, or in North Wales or the Highlands. But perhaps the outstanding meets of the thirties, from the point of view of breaking new ground, were those in the Enniskillen region of Northern Ireland.

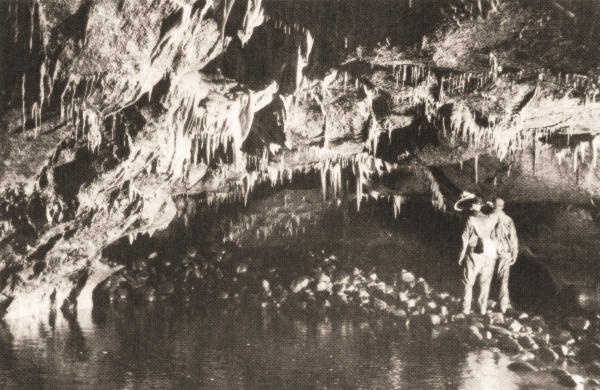

This Irish district had been visited before the first World War by a party of Ramblers, which included Alexander Rule and Harold Brodrick, and it was largely at the former’s instigation that the idea of another visit was raised, with the particular objective of a serious exploration of the Marble Arch system. As a result, I was given the job of organising the four meets we held there in the thirties.

Arranging the meets was quite an undertaking as it involved not only getting the party together, but making mass bookings on the Heysham to Belfast steamer, booking accommodation at the Imperial Hotel in Enniskillen and obtaining permission from the noble Lord (Lord Enniskillen) to visit the Marble Arch area. Ernest Roberts and I once had tea at Florence Court, with the Earl. He turned out to be a very pleasant man who was much looked up to in the district as a model landlord. He came into the inheritance after it had been somewhat neglected by his father, who milked it in order to live grandly at the court of King Edward VII. The present Earl was very keen on forestry and showed us with great pride some of his fine trees and his forest nursery. It was from him that I learnt that the Churchyard Yew, so common in every English churchyard, originated from a single shoot on the Florence Court estate.

For the first twb meets I arranged the hire of a car in Belfast so that we could have transport, not only for getting to Enniskillen, but between that town and the caves. I well remember how, having arranged for the car to be on the dockside when we berthed in the early hours of Good Friday morning, we duly disembarked to find no car! Having whiled away a couple of hours, we found the garage and were received with open arms and led to the waiting car. When I pointed out that they had promised to have it to meet the ,boat,they explained that the hiring day did not start so fearly. And when I produced their letter promising this fact, I got the delightfully Irish reply: “Sure, Sorr, that’s only a figure,of speech!” Like the first meet, the second was at Easter and, having taken across my own car, after the meet I tqok Roberts down to County Clare where we joined up with another party to explore the wonderful cave systems in the Burren around Lisdoonvarna.

Then came the war and all activities were suspended, with the exception of annual committee meetings, which I attended – the committee remained in office en bloc throughout the war. The Club had a committee room, where the library was kept, in Albion Street, adjoining a solicitor’s office. During the war the Club moved to an institute on the other side of the river and then, when the library was handed over to the Leeds Public Library, we gave up having a headquarters.

After the war, although I continued to attend meets, the wartime interruption was too much for me and I never took up pot-holing or rock-climbing again, though I still did plenty of fell-walking. It is true that in the late fifties, and more particularly in the sixties, when Richard became an active member, I got to know some of the younger members of the Club, but as one by one death took the older members, I found myself knowing fewer and fewer at each Annual Dinner I attended.