Karakoram Trek, 1989 – A Personal Narrative

by T. A. Kay

A photograph or perhaps a description of a mountain is sometimes sufficient to fire one’s enthusiasm to go and climb the mountain or experience the same view. The first time I saw a photograph of Liathach rearing above Glen Torridon I knew I had to see and climb it. A few years earlier I harboured a similar ambition after seeing a photograph taken by an American, Galen Rowell, a circle of high, snow-covered mountains in the Karakoram, viewed from a glacier position called Concordia. Further reading indicated Concordia as being in one of the world’s remotest regions within afew miles of Pakistan’s borders with India and China and not far from Afghanistan and Russia.

In May 19891 joined atrekking party, aimingto reach Concordia via the Baltoro glacier. At Heathrow I met the rest of the party; six men and three women, all seasoned travellers. Quickly we realised we had a lot in common, as well as a desire to go to Concordia. We acquired a cohesiveness and became a team; very desirable, if you are to spend a month together in remote mountain country.

We landed at Islamabad next morning and encountered two aspects of the East; the intense heat, despite the early hour, and that unmistakable smell, which can only be described as slightly sweet and dusty. Our trek leader was there to meet us. A capable person, very Australian, complete with wide-brimmed hat.

The Pakistan authorities require all trekkers to the Karakoram to be accompanied by a Pakistani guide. Ours was called Mohammed Iqubar. A little rotund figure, who clearly liked his food. His appearance, however, belied impressive fitness and energy. He became our “Mr Fixit”, a man of considerable influence with many contacts. Another requirement of the Ministry of Tourism is that we attend a briefing, because the Concordia and Upper Baltora Glacier region is a “restricted area”, and only afew miles from the cease-fire line with India. The briefing amounted to “instructions” not to photograph any military personnel or installations and suspension bridges. Men in the party were specifically told not to photograph Pakistani women.

Despite rising at 4.00 am next morning, our plan to fly to Skardu was initially delayed and then cancelled by 8.00 am. The descent into Skardu from 26,000 feet beside Nanga Parbat to 6,000 feet in the Indus valley over a ten-minute period requires visibility which did not exist that morning. Our only alternative was to travel by road, for which our “Mr Fixit” obtained a 20-seater Mercedes coach, with two drivers and two other assistants. For the first five or six hours we drove on quite good surfaces, metalled in the main, though the road switch-backed up and down valleys. Secretly, our forced journey was one which I had long dreamed of making and proved to be an incredible experience. The scenery was superb. Later, after dark, we arrived at a hotel, where we spent the night.

Next morning we were away by 5.00 am and soon joined the main route of the Karakoram highway, which follows the Indus river for about 600 miles. The highway has simply been hacked from the steep valley side and is no more than an artificial ledge. Above and below are steep, loose, rocky slopes with the raging river at the bottom. There are frequent landslides. Whole sections of the road surface have been torn away by debris clearance, leaving many miles of loose stones and earth.

We continued along the highway, crossing the Gilgit river by a long suspension bridge, where it joins the Indus, and were stopped for the usual inspection by the Army, who told us the road was blocked about 20 miles ahead. It was late afternoon, the light was beginning to fade, but we decided to press on. Our driver had been at the wheel for 12 hours with only a lunch-time rest and he was tired. Nearly an hour laterwecameto a landslip strewn across the road. It was three feet high but only ten feet wide. The driver paused to look at the blockage, then accelerated towards it, hoping to clear it by brute force. He failed and the bus became stuck. Fortunately the vehicle had not veered left or right, for immediately to the right the valley plunged 300 feet into the Indus.

We tried in vain to push the vehicle backwards then forwards without moving it. In vain, we began to scoop away the rocks and soil with bare hands, as the bus carried no spades, picks or tow-rope. A thunderstorm was only a little way up the valley. It was virtually dark and we were threatened with more landslides. There is not a lot one can do in such a situation but hope something will turn up, Inshallah (God willing).

Something did indeed turn up, two minibuses, which approached from the opposite direction. Goodness knows where they had been buttheywere intending to go to Gilgit. Apart from one passenger they were empty. Our Mr Fixit again proved his worth. He persuaded a minibus driver to return with us to Gilgit, where we arrived at 11 pm. One of my aims of visiting Gilgit someday had been fulfilled, even though it was entirely unscheduled.

Much later the next day the party left Gilgit in a van and fou r jeeps. We encountered other landslips without mishap and finally reached Skardu in the late evening. The journey, 45 minutes by air, had taken three days along the Karakoram highway, but it was an experience I would not have missed.

Next morning a further five hours by jeep took us to the village of Dasso and a meeting with our porters at the nearby camping-ground of Biano. Six days after leaving the UK the trekking was at long last about to start. Already in residence were a group of British women, who were aiming to climb Gasherbrum II, and a French expedition for an attempt on Broad Peak.

Next morning the hiring of porters was completed and loads allocated. Apart from the pu rchase of a goat, there was no chance of buying food for ourselves or the porters. Not only had we to take all our food and equipment, we also had to hire extra porters to carry food for the trek porters. It was also necessary to provide food fortheir return journey when no longer needed by the party. It is the old problem which must be faced whenever a journey is planned through country where supplies are unavailable; man is an inefficient “beast of burden”, who eats more in proportion to his carrying load than a four-legged animal. Our party of ten trekkers, a leader and a trainee leader needed 70 porters in the early stages of the trek, which reduced to about 20 porters in the final stages.

The loads were allocated and we were away by 7.30 am along a continuation of the jeep track. One and a half hours later we passed through a tiny gathering of houses, all built from mud and stones, and stopped for a short while. Here we experienced for the first time the walking style of the porters. Without exception they would start off at a fast rate, certainly faster than oneself wanted to go, and after a mile or so would stop and rest their loads on boulders.

Whilst they were resting we invariably passed them. When they moved off again, it was at the original pace and they soon overtook us. This happened time after time and at first, perhaps smugly, one thought this was a classical “hare and tortoise” situation and that we, the tortoise, were bound to arrive first at the destination. How wrong we were; almost without exception they arrived first, despite carrying 50 lbs and occasionally more.

Later that morning we descended towards the river on loose rock and soil. The river was confined to a deep, narrow, rocky cleft some 300 feet below the upper lip like a huge version of the Strid in Wharfedale. About 12 feet wide, the cleft was bridged by tree branches and three or four planks. It certainly concentrated the mind wonderfully to cross the “bridge”, whilst peering at the river below. Our campsite was a little further up the valley on a sandy, dusty spot near the entrance to the Braldu Gorge.

Next day we were up at 4.30 am and away by 6 am. The sides of the gorge are about 5,000 feet high and consist almost entirely of loose boulders and scree, all at precarious angles. It is correctly regarded as one of the more dangerous parts of the trek. For most of the passage we were boulder hopping close to the river edge and climbing rock bluffs too steep to scramble round. To escape the gorge we finally climbed a large spur some 2,000 feet high. Under the hot sun it was hard going even for the porters. Once at the top there was a mad scramble-cum-scree run over very loose terrain back to river level.

We reached the village of Chongo, afew mud and stone houses partly built underground. In winter the animals and people live together for warmth beneath the snow and emerge only occasionally. There have clearly been years of inbreeding, for a number of the inhabitants, adults and children, had wizened features. A flock of goats was as wizened as the people tending them. I was reminded of a passage in George Schaller’s book, Stones of Silence, written when he passed this way 15 years earlier. “At intervals we passed through hamlets where stunted men with scraggy beards and wrinkled faces resembling desiccated turnips watched us pass, and women fled at the sight of us, their brown and black rags flapping like the wings of giant crows.”

Beyond the viIlage we found good water and had a lengthy lunch stop in the shade of some trees. There followed a hot three hours’ walk to our campsite half a mile before Askole. Situated amongst trees and by an irrigation channel, it was a superb spot at an altitude of about 11,000 feet. I did not sleep well that night. Reluctantly, I decided to take Diamox, as we would be going higher each day. It makes the fingers and toes tingle occasionally until they almost feel numb, but its main effect is to overstimulate the kidneys. One has to drink a lot of liquid, up to six litres a day, and get up at least twice each night. Despite the side-effects, I slept soundly again and felt better able to cope with the altitude.

Some two miles beyond Askole we forded the river, half a mile from where it emerged from the Biafo Glacier. After a few seconds in the water my legs and feet had virtually lost all feeling and the crossing became a precarious venture. This was followed by a second, shorter crossing and an hour’s walk over dry river boulders to a lunch stop at Korophan. The afternoon heat was intense as we continued our boulder walk up the valley. Three more river-crossings were made; none so cold or rocky as the first. Our campsite for the night was a sandy, windswept spot called Bardumal. Its one virtue was a lovely view up the valley to one of the outlying peaks of the Masherbrum range.

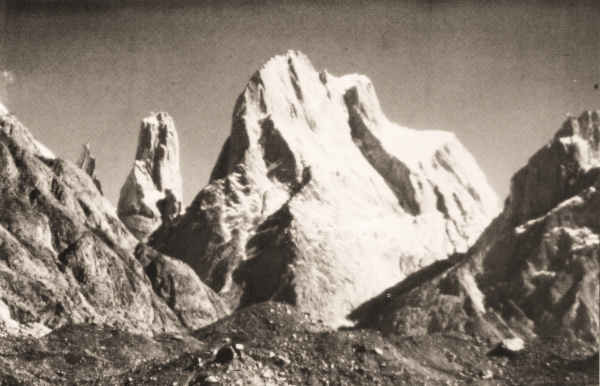

Next day, our destination was a campsite known as Paiju, about seven hours’walk away. Our progress alternated between following the river, sometimes boulder hopping in the river itself, traversing long, sandy stretches of scree or climbing in and out of gullies by the side of the river. But we were beginning to see the shape of the mountains, where we were to spend the next two weeks. First, Paiju Peak (21,650 feet) from an unusual angle, then glimpses of UN Biaho (19,957 feet), the Trango Towers (20,528 feet) and Cathedral Towers (19,245 feet).

Paiju campsite was in a narrow valley leading down to the main river valley. We hacked out level sites for our tents. The porters used an underground “hut” and stored food therefor collection on the return journey. We shared the site with the British ladies and French expedition. Next day was a rest day, so that the porters could prepare extra bread before moving on to the Baltoro Glacier. It was one of the few bad weather days, a minor sandstorm followed by rain and mist. Porters from the other two expeditions went on strike for more provisions, a common occurrence on remote sites as they “hold all the cards”. There were clearly no hard feelings for later that evening there was a grand British/French/Pakistani camp singsong and dance. The porters showed their musical skills by playing “drums” very effectively on expedition barrels.

We spent the following day moving up the Baltoro Glacier. The moraine was loose and rough, the walking was slow. Later, on a lateral moraine, conditions improved and there was even a semblance of a path. Although it was slightly misty, the views of Uli Biaho improved all the time. We passed the old campsite of of Liligo, which had been obliterated by a huge landslide two winters earlier. A new campsite had been found 20 minutes away. Like the original site, it was just off the glacier with high, loose cliffs rising vertically behind. It was as precarious as the previous site. Confirmation came in the night when a substantial stonefall passed within ten yards of the tents.

Our journey next day was dominated by the Trango Towers. Fosco Maraini beautifully describes these mountains as a “regular forest of peaks, towers and pinnacles; the world does not contain a more striking throng, all in granite that ranged in colour from tawny brown to terracotta red — colours that blend wonderfully with the white of the snows and the frozen bluish hues of hanging glaciers, seracs and crystal-still cascades”. We walked across a frozen lake, where the Liligo Glacier meets the main Baltoro Glacier and over loose moraines. There was a small stonefall with one member taking a partial hit on his rucksack. Later we met two members of a small New Zealand expedition, who were planning to scale a face of almost 6,000 feet on Uli Biaho.

Urducas was at first sight an unpromising campsite. Littered with boulders the size of houses, it sloped down very steeply to the glacier. Ice-gullies flanked each side, whilst a spur of Masherbrum looked down from behind. But it was a surprisingly sheltered spot with the boulders shielding us from falling debris.

After a cold night and a late start we arrived mid-morning at a flat part of the glacier called Biange and rested. Masherbrum (25,600 feet) soared up to the South, the top tipped with a large cone of ice. Above Biange we passed remarkable ice formations. Initially they were pyramid-shaped and gleaming white. Others looked like huge pointed hats, 40 or more feet high, formations unique to the Baltoro Glacier.

Sunday, 28th May, was to be the culmination of the trek with our arrival at Concordia. We had left the campsite at Gore early and soon had our first views of the Muztagh Tower to the North. As we progressed up the glacier, it constantly held our attention and showed a totally different outline from the standard photographic viewpoint. Gradually, Gasherbrum IV (26,180 feet) began to dominate the scene, a peak of perfect symmetry. Gasherbrum I (26,470 feet) could be seen peeping over one of the ridges.

At last, we arrived at Concordia, the “Golden Throne of the Mountain Gods”, two names given by Sir Martin Conway, a former honorary member of the YRC. According to our Pakistani guide, Concordia is reached only when K2 is in view and, sure enough, northwards along the Godwin Austen Glacier was K2, a mere 12 miles away. Marble Peak formed the left side of a perfect picture and Broad Peak (26,400 feet) the right side. By walking across the moraine towards Gasherbrum IV, Chogolisa (also known as Bride Peak — 25,110 feet) came into view.

We spent three days at Concordia and saw the whole circle of mountains in every shade of light. Although our visit did not coincide with the full moon, the millions of stars throughout each night were more than enough to light the scene. Dawn, with the sun coming up over Gasherbrum IV, was a veritable explosion of light. By contrast, the evening was soft and mellow, the rays of the sun transforming the highest mountains into gold.

Very early on the third day we struck camp and began our move down the Baltoro. The glacier had changed significantly during our stay in Concordia. Much snow had melted and the glacial streams were faster, wider and deeper. We cam ped on the glacier at Biange and heard the ice moving beneath the tents. Lower down the glacier the terminal ice was in a dangerous state. Huge sections were seeping water. They were cracked and on the verge of collapse. We moved further down towards the Korophan, Chongo and finally Skardu. Sadly, the trip was virtually over.

Sometime later, as our Boeing 737 climbed steeply out of Skardu, we saw within minutes K2 and the adjacent peaks 100 miles away. They were like old friends. Minutes later we passed close to Nanga Parbat. Thirty-five minutes later we were once again in hot Islamabad.