Farthest North And South

by W. T. D. Lacy

As one looks back on life, it is strange how one particular incident has led on to another.

In 1913, when I was six years old, I was standing in the roadway at Hawsker with my mother, when a man came up to us and handed her a parcel and said, “Keep these for the lad — tell him they are from Scott”, and walked on. Inside the parcel was a thick woollen undervestand two nodules of rock. I never saw the man again. He was the son of a plate-layer who worked on the Scarborough to Whitby railway — he had run away from home and been missing for several years. When he turned up at home his father said to him, “Where has thou been all these years?” and he replied, “I’ve been to the Pole with Scott.” The father said, “If that’s the best bloody story thee can tell me, get out of the house before thy mother sees thee.” I was excited by it all and in the village Wesleyan Chapel I found the two volumes of Nansen’s Farthest North, which I read many times.

When I was 21 years old I was pressed into entering a local eisteddfod and was su rprised to win as af irst prize the book, South with Scott. The frontispiece contained in detail the names of the expedition members but the name for which I was looking was missing. Saddened, I turned the flyleaf over and there under the heading of “The Ship’s Party” was the name, James Skelton, Able Seaman; the man who had given me the parcel years before had told the truth. By then I too had decided to go to the Pole.

One day, some years later, when I was manager of a bank in Didsbury, I was inspecting the contents of the strong-room and came across an Arctic Medal. This discovery caused me to write to the owner, who suggested I got in touch with one of the Norwegian shipping companies sailing from Troms©. I also contacted a Norwegian customer, who some weeks later introduced me to his brother, who was on holiday but happened to be the director of an Arctic broadcasting station in Troms©. As a result of our conversation I was surprised to receive a letter stating that a berth awaited me aboard the S.S. Lyngen, which was about to make a voyage to Spitsbergen. Excitedly, I telephoned the bank’s head office in London and received special leave to make my first Arctic voyage.

I travelled from Newcastle to Bergen and from there to Troms©, where I joined the S.S. Lyngen. As the ship slipped its moorings, Amundsen’s dog-driver was on the quay to wave us off. He was the only man then alive who had stood at the North and South Poles.

We sailed past Bear Island and up the coast of Spitsbergen to Longyearbyn, where there is a coal-mine. The miners lived in a hostel and after a two-year stint had saved enough money to allow them to return to Norway and buy a small homestead on one of the fiords. In Longyearbyn were several trappers waiting to sail with us up to the North-west corner of Spitsbergen. They were to be dropped off at various points along the coast, where they would remain over the winter period.

It was a most interesting voyage, seeing glaciers coming down to sea level. At one point I went ashore and walked along the beach to get a better view of one of the glaciers. As I got closer I realised it was about to calve an iceberg. I was in a difficult position. If it broke whilst I was on the beach, I might be swept away by the tidal wave it would create. Hastily I set about climbing the cliff face which backed the beach. On reaching the top I walked back to where I had come ashore. To my horror I saw the Lyngen had left without me and was already heading out to sea. I shouted and waved frantically until I was eventually sighted; the ship stopped and put a boat ashore for me. It was one of the most hectic moments of my life.

I eventually made three trips to the Arctic regions, including Greenland. Much later, in 1989, I read a report that an American, Skip Voorhees, was trying to arrange a trip to the North Pole in a Twin Otter aircraft. I contacted him immediately. Pleased with his response, I made the necessary arrangements to go on the trip. I was a bit worried on account of my age, for I was then 82 years old.

On 4th April 1990 I flew to Edmonton, Canada, where I met the other members of the party. There were eight of us, including Skip Voorhees, the leader. Three days later we flew North via Yellowknife to Resolute Bay on Cornwallis Island in the North-west Passage, where we spent the night. From there our plan was to fly to Eureka, a weather-station on Ellesmere Island, and on the way make a diversion over the Magnetic Pole. But our start was delayed, whilst we waited to hear whether another aircraft had been successful in dumping fuel for us at a cache between Eureka and the Pole.

Our Twin Otter eventually got away at 14.10 hours on Sunday,8th April. As we approached the Magnetic Pole, the visibility was very bad and the surface ridged with pressure ice. After flying around for a little while, our pilot made a “touch and go” landing at 16.10 hours before heading for Ellesmere Island. The sun came out as we flew by its Western neighbour, Axel Heiberg Island, and the mountains of the 7,000 feet Princess Margaret range were a wonderful sight. We landed at the Eureka weather-station at 18.12 hours and were privileged to be given accommodation at the Government building, which is run as a club for weathermen, pilots and fellow travellers.

We had planned to make a dash for the Pole on Monday, 9th April, but the weather was poor — a low pressure area was coming across from Siberia. The weather forecast predicted high winds and poor visibility, which was unusual for the time of year. Despite the gloomy news, an aircraft flying within 40 miles of the Pole reported improved weather and a rising barometer. Skip and our pilot thought the improved weather might last for eight hours or so, which was sufficient time to make a dash for the Pole. We left Eu reka at 11.59 hours, just seven of us and two pilots, five barrels of fuel, each holding 208 litres. The spare fuel left no room for Skip. There was also the point that it was wise to leave someone at base to supervise any emergency help.

We flew at 10,000 feet into a head wind. The visibility was zero, our airspeed was 116 knots and from time to time we encou ntered turbulence. At 15.26 hours we began our descent to the refuelling stop. Visibility was still very poor, when quite suddenly we were out of the cloud and, standing on the ice 30 or 40 feet below us, were three men behind barrels of fuel. What exactitude! It really was a thrilling sight and equal to any military exercise. We had been flying for approximately 31/2 hours in very poor visibility and had landed within 100 yards of our fuel cache. Wonderful!

The cache was at 86° 18’N, 76° 52’W. I walked around the area and took photographs as the aircraft was refuelled. Nearby two tents had been erected for the refuelling team. They would be picked u p next day. We took off agai n at 16.28 hou rs. As we flew North, the weather gradually improved and the sun broke through. In the cockpit an instrument began to waver between 89.265°N and 89.672°N. We were getti ng very near to the Pole. The ai rcraft tu rned and circled as we looked for a clear area to land. Suddenly we sighted a level area, free of hummocks but surrounded by pressure ridges. Down we came, bumped, rose into the air again, then landed at the North Pole at 18.30 hours.

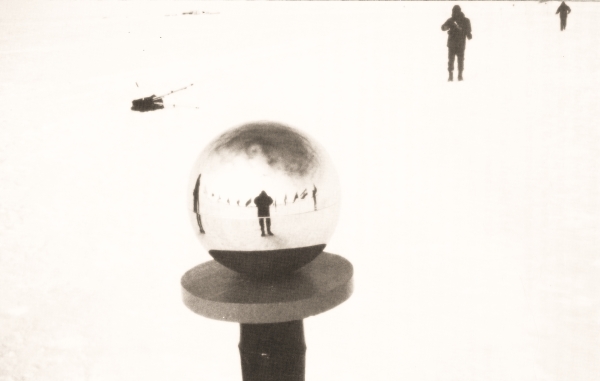

The sun was overpowering and the snow glittered, as I jumped out of the aircraft into the cold air. It was -40°C. I must have been standing on the cleanest, purest spot on earth. We took photographs of one another before I went for a walk around the Pole — or was it around the world? — and fell into a concealed crevasse. I was held at my hips until pulled free. Below was 13,000 feet of water.

All too soon we climbed back on board the Twin Otter for our return flight to Eureka. We had been at the North Pole for about an hour. We had kept one engine running all the time, then each engine was revved in turn and then both together. We were ready fortake-off. The aircraft shuddered and shuddered butwould not move. After more shuddering we realised our skids had frozen to the ice. Again and again we tried but could not break loose. Inside the aircraft we moved around in the hope of breaking the adhesion and failed. We crowded into the tail section and endured more shuddering. The engine noise was deafening. After more shudderingand much rocking of the aircraft, we finally broke free. What a relief! It was 19.56 hours and we had been stuck to the ice for 20 minutes.

As we flew South the weather report from Eureka said visibility was decreasing. Our pilot decided to land again at the fuel cache and take on more fuel in case we could not land at Eureka. We landed at the cache at 21.28 hours. An inspection of the aircraft found the heating system to be failing and some running repairs had to be done with sticking-tape before taking off again.

The weather began to improve, the sun came through and the temperature roseto-15°C. Eureka reported increasing visibility. But it was temporary. We flew into deteriorating weather again and landed at Eureka in very poor visibility at 01.22 hours. Our journey time from Eureka to the Pole and back again had taken 13 hours 23 minutes. A hot meal awaited us and then it was off to bed. The completion of a very memorable day.

As one ambition is realised, so another inevitably takes its place. My earlier visits to the Arctic had been inspired by Scott’s journey to the South Poleand my thoughts began to turn in that direction. In 1991, and now aged 84 years, it was arranged that I should join Adventure Network International’s party, which was organising a visit to the South Pole.

On 11th December, I leftTeesside airport and arrived in Santiago, Chile, two days later minus baggage. It had been lost somewhere along the route from New York. I made enquiries at the airport desk, completed a search form and was given US$150 to buy necessary items of clothing. Not much money to re-equip myself with clothing for the Antarctic! Later in the day, a delayed departure caused us to arrive in Pu nta Arenas at 23.30 hours. A long day. This particular Friday, apart from being a long day, had proved to be a real 13th.

I was taken to the Hotel Cabo de Hornas, where I slept well. At breakfast I met Guy Johnson from the USA, Elizabeth Phelps from Australia and ANI’s representative, Anne Kershaw. I learned that Elizabeth had reached the North Pole a year before me and was hoping to become the first woman to visit both Poles. My baggage had not been traced until a telephone call in the afternoon said it was in Santiago. Our flight to Antarctica the next day, Sunday, would wait until my baggage had arrived.

Sunday came and went. My baggage arrived but the flight South was delayed by bad weather in Antarctica. I walked around Punta Arenas and was surprised to see little birdlife. One sparrow, one pigeon, one seagull were the only birds seen. We eventually left at 11.20 hours on Monday on board a DC6 aircraft built in 1953. The route South took us over the Magellan Straits and then Tierra del Fuego at an altitude of 9,000 feet. Our destination was Patriot Hills, 1,935 miles away, with the South Pole a further 580 miles beyond. There was little to see. After passing the first ice-floes we flew above the clouds until we sighted the Ellsworth Mountains close to Patriot Hills, where we landed at 19.02 hours.

I was in Antarctica. Our base camp, a short snow-skidoo ride away, was a large tent for cooking and eating and several smaller tents. Approximately 100 yards away was an igloo lavatory, a wall of snow-blocks without roof, which gave me some shelter from the wind. After a meal I crawled into my sleeping-bag and was soon asleep.

The following morning I was able to take stock of the camp, which was at an altitude of 2,860 feet, some 30 miles from the coast. High winds had produced a dramatic landscape by sculpting it into a corrugated sea of irregularly shaped snow-forms known as zastrugi. I went on the pillion of a skidoo to take photographs of nearby hills. The temperature was -3°C Later in the day a party which had been climbing Mt Vincent, 16,067feet, returned to camp. They had been weather-bound at Camp 3 for six days. There were 30 people for dinner that evening. Outside the sun was shining brightly despite the late hour of the day.

Next morning, Friday, 20th December, we woke in fine weather. The wind had dropped, so it was decided to fly to the South Pole. Our aircraft was a single-engined Otter. On board the windows were iced-up, so I took photographs of the seven passengers. After a two-hour flight we touched down in a five to ten knots wind at the Thiel Mountains refuelling point. The time was 15.40 hours, our altitude was 5,250 feet and the temperatu re was -12°C. An hou r later we took off on the last leg to the South Pole. For most of the time we were above the clouds at 12,000 feet and I wore an oxygen mask in the unpressurised cabin. At 19.25 hours (Patriot Hills time) we landed at the South Pole. The weather was poor and the temperature was -27°C.

We went to the Amundsen-Scott base and were told by the Americans, who run it, that we could not enter until 19.00 hours local time but we could use their lavatory. The base is built about 50 feet below the su rface snow and consists of portable buildings, tents and other constructions and is surmounted by an aluminium dome. Within are numerous offices, living-quarters, dining-room and a library. Between 19.00 and 20.00 hours the shop is open. It is little more than a small bar, selling drinks, simple clothes and postage stamps. During the summer months 135 persons are employed, doing work of a scientific nature. Only 22 persons remain during the winter.

A short distance away was the Geographic Pole, where a barber’s pole had been erected and surrounded by the flags of many nations. We took photographs of the base and ourselves before returning to the aircraft. There was little to do as we sat there for three hours, waiting for a weather report. Later we began to question whether we should sit it out or move off. We decided to depart. The aircraft taxied to the refuelling point a mile or so away and the tanks were filled. Another change of plan — we decided to wait a little longer for the weather to improve. There was a risk that we would have insufficient fuel to reach Thiel Mountains.

After a brief visit to the American base, where everyone was very kind to us, we rejoined the aircraft and took off at 1735 hours (Patriot Hills Time) for Thiel Mountains. We flew at 14,000 feet and I was given an oxygen mask. The head wind began gusting at 45 knots and, with the cruising speed of the Otter being 90 knots, it soon became clear we could not reach the next refuelling point. We turned around and hoped the wind would help us to reach the South Pole a second time. We landed at 20.20 hours, the Otter was refuelled, and a tent erected. I laid out my sleeping-bag and was soon asleep.

Later the next day, Sunday, 22nd December, it was decided to make another attempt to reach Thiel Mountains at 85°S 87°W. We took off at 14.20 hours and landed 90 minutes later after an uneventful flight. The weather was fine and the temperature was -10°C. At Patriot Hills the wind was gusting at 125 knots. The Otter was refuelled, whilst I and others took photographs. There was little to do but wait for the weather ahead to improve. Mr Nishie, a Japanese gentleman, asked metojoin him in drinkingto “Johnnie Walker”. He said in halting English. “I speak from my bottom — the bottom of my heart.”

At 22.00 hours the weather was still bad at Patriot Hills, so we flew to a lower altitude site 20 minutes’ flying time away, where there was less risk of encountering low cloud at take-off. Our new location was named Coffee Plateau. The tent was quickly erected. Three and a half hours later I crawled into my sleeping-bag after a meal of soup, sausage and Irish whiskey. I awoke about noon next day and learned that the weather ahead was still bad with snow and low cloud base. The remainder of the day was spent waiting for weather reports at four-hourly intervals and talking to other members of the party. Pat Morrow talked about the climber’s endeavour to climb the highest peak in each of the seven continents. He was well on the way to achieving that goal.

Poor radio reception owing to atmospheric disturbances heralded Tuesday, 24th December. The forecasts at 06.00 and 08.00 hours were inaudible. Two hours later the weather began to improve, so we struck camp and departed at 11.00 hours. We landed at Patriot Hills at 12.35 hours, where coffee, scrambled eggs and toast awaited us. It seemed like home from home.

Spending Christmas day in the Antarctic was a unique experience. With others I went for a ride on a sledge and came back, riding pillion on a skidoo. Getting from the sleeping-tent to the dining-tentwas difficult, as the wind was gusting between 35 and 40 knots and nearly blew me over. Our dining-tent had been decorated with various Christmas trappings and looked wonderful. The meal was preceded with champagne and followed by turkey and Christmas pudding. A very pleasant evening and our last on the ice-cap. We left Patriot Hills next day and arrived back in Punta Arenas at 04.50 hours on 27th December.

So ended my journey to the South Pole. At the time of writing I am the oldest person to have been there.