Norway, 1991 – A Reconnaissance Trip In The Steps Of Slingsby

by J. D. Armstrong

“Come to Norway 1992” exhorted our President in his circular of Spring 1991, as he strove to get us thinking of the club’s centenary project. Yes please, said one part of me, but the other part was aware of domestic commitments in train forthe summer of 1992. So, when my plans for the 1991 Alps Meet did not crystallise easily, I was open to the invitation by our President, Derek Smithson, to join him (“You’re a disciplined sort of chap”) in a reconnoitring expedition in 1991. Better go in 1991 than not at all. Give the Autoroute du Sud a miss for a year. Getaway from the garish crowds of the popular Alpine centres. Just two of us, three weeks, away from it all, to see where Slingsby had been. I accepted.

My set book for the trip was Norway, the Northern Playground, Slingsby’s book, published in 1904, when he was 55, with 25 years of mountaineering behind him[1]. This has now been reformatted in chronological order by Jan Schwarzott and is awaiting publication. Derek sent me an early draft, on A4, printed on one side and two-and-a-half inches thick. He had kindly marked the passages relevant to ou r jou rney. About two weeks before we were due to leave I sat down to tackle this monster. I can only say I found it fascinating. I found myself reading much more than the set reading. Slingsby describes his mountaineering in a modest and accurate style, similar to Peter Boardman’s, and also includes comments on the customs, folklore and history of Norway. My admiration for him began to grow. He did so much on his famous Leeds nails. A good day out for him was often 21 hours. My mind began to attune to the days ahead, keen to see the terrain he had covered. I was not to be disappointed.

We took all our own food (except bread and milk). Derek acted as quartermaster and, as he had the maps, he decided the routes. It was, after all, his show. My responsibility was to have a car big enough to take our gear and supplies, and to be fit enough to keep up with him, made possible because he carried twice as much as me.

The trip was from the 1st to the23rd August and was to be in three parts: Sunnmore to begin, because it is Derek’s favourite area, Jostedalsbreen because of hopes of crossing the ice-cap, and finally Jotunheimen. Between parts one and two, an excursion to Oslo had been inserted to see Jan Schwarzott and to meet influential people who may be able to help us in 1992. It also involved, at Jan’s invitation, going to a concert to hear Vladimir Ashkenazy with the EC Youth Orchestra play Mahler’s Symphony No.3 in D minor. No more need be said here about that trip except to say that the concert was so good that Derek admitted he did not go to sleep.

Our first camp was in Sunnmore at Hjortedalen at some 680m. The aim was to climb Storhornet (1,599m). Slingsby had climbed it in 1881 but he had started from the other side at Grodas. Storhornet for him was an interlude along with several pinnacles, when maki ng a new glacier pass to Bjorke. We wanted to see where and what these were. We set off early, ascended by way of Blabreen and found on the West (our left, as we were moving North) two sharpish knolls. These, Derek declared, were Slingsby’s pinnacles. So over them we went, descended to the glacier which was well covered in snow, and ascended a snow-field without difficulty to the ridge. We had lunch waiting for the cloud to lift to let us see Storhornet. It did lift, so along the ridge we went to the summit. We found a metal canister with pencil and book to record the names of ascensionists. One person climbed it last year and two people had climbed it from Bjorke the day previously. Otherwise no one else had been in two years.

That night our greatest hazard was cows. I, having fallen asleep early, was assured next morning that Derek had twice had to rise to ward them off, drawing on his choice Anglo-Saxon vocabulary forthe purpose — some of us have heard similar sounds, when a boot has descended near our rope. The cows were suitably chastened and sought pastures new.

Next day, we moved North, crossed Hjorundfjord from Leknes to Saebo and found a campsite in Standalsdalen just below the impressive ski-hut in that valley. Our aim was to ascend Kolastinden (1,433m). Slingsby climbed it in 1876. It was his first mountain in Sunnmore. He started at fiord level, not like us at 600m. He ascended by way of the “fan-shaped glacier — Blabreen”, cutting an “icy highway”, which his companion would not follow. Whereon he had carried on alone and his description of route finding that day alone on glacier, ice and ridge, often in cloud, is breathtaking. The glacier has retreated since 1876.

We found ourselves trying to reach the ridge (very like the Cuillins) by the greasy rocks of the South-east side, until we came to an impasse. So we traversed left and gained the ridge lower down. This did not permit great progress and we were forced once more back on to the face. Now the rocks were coated in lichen, inches thick but, with the help of an ice-axe, upward progress was possible. So we gained the ridge and I admitted to being exhausted from the uncertainty of the lichen footholds. We were in cloud now, so the exposure was hidden from our eyes. But you could feel it and across the glacier the pinnacles of Sunnmore (Slingsby calls them “cathedral spires”) kept emerging and retreating in the gently swirling spectral wraiths.

The summit of Kolastinden is the tallest of many pinnacles along the ridge but, when on the ridge, it is difficult to say which that is. On his famous ascent, Slingsby climbed several but was never sure if he ascended the tallest. Other experts say he did not. What was clear to us was that to progress along the ridge was similar to, possibly sharper than, the Cuillins. We saw that, to get to the taller pinnacles of Kolastinden, the ridge should be gained further to the East, using the glacier.as Slingsby had done. We decided to descend, losing the way (I was leading) and getting soaked in the afternoon rain and wet, thick vegetation.

The following day we moved back over Hjorundfjorden, admiring the dramatic view of Slogen (“a pyramid”, writes Slingsby, “so sharp I have not seen it equalled at Chamonix or in the Dolomites”) descending 1,800m from its pinnacle summit straight into the fiord. We remembered that Slingsby had climbed it from Saebo, which meant crossing the fiord twice, in one of his 21-hour days.

We left the car at Skylstad and back-packed up the path to the Patchell Hut (950m). The path was relentlessly steep, made more difficult by overhanging branches. As the gradient eased off, the way became bestrewn with boulders. With tired legs and heavy packs the path was hard to see. The relief when reaching the “bandet” cairn is intense. But, in Slingsby’s days, no path existed and he pleads that one should. Despite its unremitting steepness and final boulders, it is a good path, taking you into the very heart of superb mountains. We were undecided whether to camp or to use the Patchell Hut, but, as Derek had left the hut key in the car, the decision was made for us.

Our first objective was to be Little Brunstadhornet, climbed by Slingsby in 1899 with a young party of son and nephew. Our way was over the shoulder between Slogen and Brekketind, crossing a snow-field, ascending to the ridge and so to the summit. We set off in clear weather and, once over the shoulder, there before us was a marvellous mountain,free of all cloud. “That’s it”, cried Derek and across the snow-field we went and began to scramble up the rocks to the ridge. Once on the ridge, we left our rucksacks and took out the rope. We ascended first one, then two and then three pinnacles, thinking each one must be the summit. After three of them Derek said that was it (or words to that effect). It was probably the Eastern summit, not the absolute top. It was, however, a good spot and we enjoyed it. We retreated along the ridge to recover ou r rucksacks and scrambled down the rocks to the snow-field. As we recrossed the shoulder we looked back at our mountain, standing proud in the afternoon sunshine. It was then that we consulted the map, and to our consternation found we had climbed Eastern Velleseterhornet (1,330m), not Brunstadhornet! We could not believe that we had climbed the wrong mountain and one which Slingsby did not ascend. But it was so. Tomorrow we must make good.

The morrow proved wet. The wind had swung to the West, the clouds hid all the peaks and a wet spell looked probable. So reluctantly we packed up and descended to the valley. There we found that I had left on the lights of the car and the battery was flat. But with the help of a friendly farmer with jump-leads and the good luck that another climber drove up at that moment, we were able to make good the lost power without serious damage to the battery. It was perhaps as well the wet weather had forced us to retreat early.

The next three days were as promised — wet. We spent two days camping outside Stryn with clouds almost at fiord level and rain varying from light to heavy. Our excursion to Otta in the East, the early morning train journey to Oslo and return journey on the midnight special then followed. So three days later found us camping in Lodalen near the North-west edge of the huge ice-cap of Jostedalsbreen. Slingsby estimated itwas nearly 400 square miles and over 48 miles long. (“Used as I was to large expanses of snow, I was not prepared to see such a white Sahara as this.”) But the weather remained most unkind and we were not to see the immensity of this snow plateau.

Derek had chosen this location for two purposes: to try to go up the Robber’s Pass (Tjuvskardet) and to reconnoitre Kjenndalsbreen, the steep glacier at the end of Lodalen. Slingsby had been up the Robber’s Pass and found it an excellent way to the main ice-cap. John Snoad had ascended it in 1977 with a local Norwegian as a guide. We were hopeful that, equipped with John’s detailed instructions, we could find our way. The path ascends by four zig¬zags up a vertical, rocky face, densely covered in brambles, bracken and birch trees. It looks quite impossible from below. At 720m the trees and scrub end at a fine viewpoint and easier going leads up to about 1,500 or 1,600m, where the ice-cap begins.

We spent three hours in the afternoon in wellies and over-trousers in the lush growth, which was shoulder high and very wet from recent rain. The aim was to make a preliminary inspection of the face to identify John’s initial landmark, the crack which was the key to unlocking the secret of the route. Soon Derek pronounced himself satisfied that he had got it “sussed”, so we retreated for an early night. Next day, at an early hour we began our serious attack on the route. Derek led and my job was to flatten the bracken, tie knots in reeds and twist branches, so we could find our way back. After three hours on the face, however, it was clear that we had not got it “sussed”, so I suggested we should retreat and make sure we had found the crack. “Smart arse”, muttered Derek, but he did not dissent. Once more we looked at the face and once more we looked for the crack. This time we found it and made good progress along narrow rock ledges, through the branches, even finding signs of human beings, a heel-mark and sawn stumps of branches, which encouraged us greatly. But by 2.00 pm we had not found the fourth zag and it was clear we were not going to get to the ice-cap. We were wet through and dispirited by our failure. Our descent was by no means obvious and I was grateful that Derek had had the foresight to fix fluorescent streamers to guide us back through the undergrowth.

Once more in the valley we went to look at the huge Kjenndals glacier, which in 1881 Slingsby had descended after one of his crossings of the ice-cap. His is an epic description, negotiating “genuine West Jostedalsbreen precipices, hundreds of feetwithout a ledge”. John Snoad had warned of the dangers of trying to descend such ice-falls, especially at the end of a long day. We went to see if 100 years after Slingsby the glacier was any easier. It looked as though progress could be made on the right (i.e. West) side but soon rocks blocked the route, which Derek pronounced “quite difficult”. The glacier itself looked very steep and formidable in its middle reaches.

After our rather fruitless day getting nowhere, I was glad when Derek decided we should give our legs a stretch and have a day in more open ground. The previous year he had climbed Lodalskapa (2,083m), one of the few rocky peaks projecting proudly from the plateau, but he wanted to explore another route from the North. After an Alpine reveille, we drove in thin drizzle up to Bodalen and left the car at 750m. We then followed the well-marked standard route to Lodalskapa to 1,000m and then struck off North-west into the grey, rocky mist to find a lake, Kapevatnet (1,211m), lonely and inscrutable. It was cold here and for the first time we brought out our warm clothing. Several hoary, old cairns indicated that someone at some time had been before us. The cairns were thickly coated in lichen, looking vulnerable to the winds but, once touched, proved so solid that concrete would be superfluous.

Our aim was to cross the stream, debouching from the lake, ascend the slope and then swing round to the East and so climb Lodalskapa from the North side. The stream, however, was in flood after the recent rain and there was j ust no way we cou Id cross. There are stepping-stones but these were well covered. So our way was barred and we retreated, disappointed.

We had had enough of the bad weather on the West side of the ice-cap and so we decided to move East to the Jotunheim. The Jotunheim is a much more popular region, akin to our Lake District, where marked trails lead up the more obvious mountains and through passes and where Den Norske Touristforening (DNT) and private huts provide, for about £30 per night per person, accommodation and all meals. The highest mountains in Norway, Glittertinden (2,470m) and Galdhopiggen (2,469m) are in the Jotunheim, together with the monarch of Norwegian mountains, its Matterhorn, Store Skagastolstind (2,403m), thankfully abbreviated to Storen.

With an afternoon to spare, we drove up Leirdalen to Leirvassbu (1399m), the tourist complex and centre for walking. We noted that wild camping was permitted 150 metres away from habitation and also noted that the ground was extremely stony. Campsites were not easy to spot. We looked hard at Semmelholstinden (“a pretty peak on the East that gave us half an hour’s excellent rock climbing up a steep face and along a narrowcrest until the top was reached”). The rocks on the left side of the glacier looked (at a distance) reasonable.

Next day we drove to Spiterstulen (1,106m) in Visdalen, another large tourist complex, privately run. In Slingsby’s time it was only a two-room hut. Our target was Vestre Memurutinden (2,280m), which we were to approach via a glacier, Hellstugubreen. This was Slingsby’s route of 1874, when he chose to leave the ice for the snow-field, which they found very steep. For our part we took to the glacier, having donned crampons for the first time and all other gear. I received a swift two-minute lesson on prussic knots, which I was assured would not save me if I fell into a crevasse. Suitably cheered, on to the ice we went. With only two of us on the rope and with the mist circling above us, Derek was cautious. We found a skiers’ route, marked by a few iron poles, and made reasonable progress until we met an area of new snow which covered the surface, hiding what might be below. Derekwould not go near this, nor could he thread his way through the crevasses safely. As neither of us was comfortable on this glacier, we decided that we should retreat. Derek said later, Norway was no place to take chances with the route. He repeated his personal claim to fame: that he had not climbed more mountains than anyone else. On the way down we met a sole Norwegian old enough to q ualify for the YRC, who was going to avoid the ice and tackle Memurutinden by the Eastern ridge. He was planning to camp high that night and make the summit in the morning. The value of local knowledge!

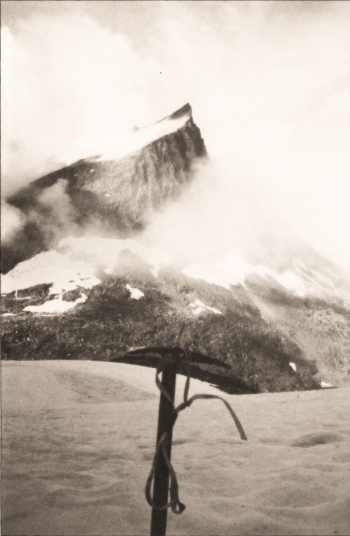

Cloud persisted the next morning but we decided we must go and look at Storen, a peak ever linked with Slingsby. We drove up Leirdalen and Breiseterdalen, passing the summer skiers en route, to Turtegro, the inn which is the staging-post for climbers of Storen[2]. We set off on a well-marked path up Skagastolsdalen, past the Tindeklubb’s hut[3], and on to a long, gentle snow-field which led to Bandet (The Band) at 1,800m. Here, perched in the lee of the prevailing wind, is the tiny DNT hut, with seven beds. Looking down the other side of The Band, we could see Midtmaradalen, straight as an arrow, falling down 1,500m into Utladalen. Above us, completely covered by cloud, was the way up to the summit of Storen, some 600 feet of “difficult” rock. We accepted the shelter of the hut for our lunch. There were several Norwegians in a working party there. As we prepared to depart, the leader asked us whether we were going to ascend Storen. We said not today. The relief on his face was a picture.

The next day was to be our last climbing day, as we were due in Ardal that evening to begin discussions about 1992. It proved to be at last a perfect, sunny day with uninterrupted views. We had our sights on Austabotntindane (2,203m), also in the Hurrungane. We drove past Turtegro once more and paid our fee to use the private, narrow Berdalen road. There we left the car just past the pay-point and began the climb in full sunshine to the East-west ridge. It may not be strictly true to say that there is no path but, as it appeared to be used so infrequently and the cairns are about a mile apart, you are in effect on your own. One of the cairns was double, two cairns about four metres apart. We christened them “The Gates of Heaven”.

After a couple of hours and covered in perspiration, we reached the West end of the ridge, which was about ten-feet wide for most of the way, and made our way along it for over a mile to the first pinnacle. It may have been easier to have used the snow-field just below the crest. We had lunch in the warm sunshine, drinking-in the wide view and using up film. Refreshed we left our rucksacks and scrambled down the end of the ridge, over a snow-bridge and climbed the second pinnacle, Derek leaving his sunhat to signpost a critical turn. Before us now was the summit, perhaps an hour away, requiring ropes. But our reconnoitring was complete and we turned round, retrieved the sunhat and rucksacks, and inglorious sunshine gently descended to the car. Then followed two days of discussions with the Ardal Aluminium Works, which are keen to develop tourism and see the proposed Slingsby centre in Ardal as an attraction. Its site is earmarked and we are invited to the proposed opening, probably in 1993.

So ended my reconnaissance in Norway. I had broadened my general mountaineering experience and, like everyone else who goes out with Derek, I had learned so many tips that on the boat I had to write them all down to make sure I did not forget them. I am grateful that he invited me to accompany him. Above all, I came to appreciate why Slingsby is so revered in Norway. I saw that in 1992 climbing Slingsby’s peaks will be no push-over, requiring long days, commitment, favourable weather and preparation. We did not reach many summits on this trip; after all, we were reconnoitring. As Robert Louis Stevenson rightly says: “To travel hopefully is a better thing than to arrive.”

The author wishes to thank Derek Smithson and John Snoad for reading this article in draft and for all their comments. Derek has put him right where his memory and notes are uncertain, and John has provided the three notes and corrected the spelling of Norwegian place-names, where this was necessary.

[1] Slingsby’s book was assembled in 1902 and 1903 from his diaries and articles published in journals both in England and Norway from 1872, the year of his first visit. Slingsby planned a second edition but it was abandoned sometime in 1917, probably following the loss of his youngest son, Laurence, in the Great War. Laurence was a very promising mountaineer and his loss was a blow, from which Slingsby never quite recovered. The new edition planned for publication in 1992, assembled into chronological order and edited in Norway by Jan Schwarzott, will include additional material right up to Slingsby’s last visits in 1921, when on the first he was received by the King in Oslo and, on the second, he dedicated a memorial in Bergen to seamen and fishermen, who also lost their lives in the Great War. Slingsby died in August 1929, aged 81.

[2] The walls of the ground-floor lounge are covered in interesting photographs, a veritable museum of mountaineering and photography in the area from the late nineteenth century to modern times. It is well worth the hotel price of coffee just to see them — and it’s a nice hotel!

[3] The Tindeklubb is Norway’s ultra-exclusive Alpine club, an organisation with a fine history but one which seems to have acquired an unfortunate reputation in recent years for ignoring correspondence from non-members.