Playing in the Snow

Derek A Smithson

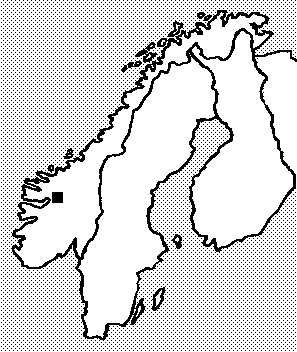

The hut, Avdal Gard, cost £5 per night, including bed, bedding, wood for the stove and all the pots and pans I could need. On its dresser were four YRC centenary mugs showing that it belongs to our Norwegian kindred club, the Årdal Turlag. In May 1995 their top huts were above the snow line giving immediate access to untold miles of untrodden snow and ice with little sign of man. I found that ski are not essential to wander in this deep spring snow.

Norwegians ski as people born to it, but the lads of Yorkshire are not born to it. However there are snow shoes. Snow shoes reminded me of crampon. They appear to have all the answers to the situation, but experience shows there is a need for some technique and courage to get the best out of them, and the particular design of shoe is important. They need only normal boots, and an ice axe for safety in steep places. I set out boldly in the mornings, when my boot barely marked the frozen snow, but the maggot in my mind was ‘How do I get back when the snow is of a depth to freeze my manhood?’ When you throw your ice axe down, point first, and it almost disappears, and you are standing looking down on it, then you think you have solved it. I have also found that my speed on most snow is the same as my normal walk with no snow But these snow shoes are not the ones usually seen on sale in Norway and Britain.

A person’s experience of new snow conditions is usually of interest. On reasonably flat, safe-looking snowfields, I repeatedly heard a shushing noise, like a minor powder-snow avalanche and similar to snow crystal sliding down a frozen surface. I could see no reason for this to occur, but it made me nervous and uneasy. I stood still for five minutes by my watch to prove I was the cause of the noise and then, after a further startling example, I retreated. A Norwegian friend explained that this is a spring snow phenomenon, when the powder snow below the hardened crust flows among the boulders. The danger is that this sometimes leads to the collapse of the crust and the passing human falls into the powder snow which could be deep.

The spring snow has other notable qualities. The snow covers all the lesser boulders and bushes so that it is easier to make one’s way, but it has to be accepted that, here in the mountains there is usually no guidance from previous human traffic. This I consider to be an advantage because I can deem myself the first person to make the journey. There were, though, times when a waymark stood above the snow to show that the Norwegians also knew the best way.

I spent my first morning in Øvre Årdal talking to two of the senior classes at the local school so that they could hear a native Englishman speaking. It was a sort of free for all with some very personal questions. After lunch I walked up to Avdal Gard (a renovated mountain farm) and as it was only 4.30pm with plenty of daylight left I decided to continue to the hut in Gravdalen. By 5.30pm I was in among the snow drifts without a clear path to follow and so I decided to return to Avdalen, which is exceedingly comfortable for those who have the privileges of members of the Årdal Turlag. The weather had been cold and dry so with an easily lit wood stove and electric cooker I was very comfortable. I never had any clothes to dry during this trip except for socks wet from perspiration inside plastic boots. When talking to Petter Løvdahl, he referred to his time in Svalbard when one of his companions had to return to base camp to allow his feet to recover from the effects of plastic boots whereas Petter, who had cleaned and polished his leather boots nightly, remained dry and comfortable.

On my second day out it took me two hours to reach Gravdalen and, having checked the hut, I walked up the valley. I had hoped to see the approaches to the two passes at the head of the valley but there was a mistiness that prevented seeing detail at a distance. Late in the evening the sky cleared and I saw again the wonderful views from the hut. The sun was shining from a clear blue sky when I left the next morning and it was cold enough to need my fibre pile jacket and to walk on the surface of the snow. I worked my way onto Gravsdalsryggen, to see the views reported by the 1992 winter party when they were here. There were tracks of all sorts of animals that I could not identify, except the reindeer. It was a herd of about twenty reindeer that I saw early in the day. They did not move away immediately, but circled and turned to face me again a few times before finally moving off. My Norwegian friends said that they would be preparing to defend their young at this time of year. Fortunately, I approached them slowly. I stopped just before the main mountain, Stølsmaradalstinden, to give myself plenty of time to descend. I was pleased to have my ice axe on some of the steep sections where there was now soft snow sliding over a base of hard snow. I might have managed without snow shoes, but there were techniques to learn. At the hut I was early enough to pack and continue to Avdalen.

After two nights in Årdal being looked after by Norwegian friends and shopping for more food, I walked up to the Årdal Turlag hut in Hjelledalen. Once more I was in glorious sunshine. The route suffered from snow drifts, before there was a full snow cover, but after establishing myself in the hut I walked up to the head of the valley to look at the routes I had planned. There was plenty of good snow and I met a couple who had skied from Sletterust and gave them tea in exchange for conversation. The next morning I set out early in the direction of Hjelledalstind, but I didn’t reach it because I was frightened by the noises from the snowfield below my feet. I did however get some wonderful views, sunburn the back of my hands and explored the area near Morkaskardet so that I was sure of the start of the next day’s journey. That day I satisfied a long standing desire to see into Morka-Koldedalen, by traversing into the valley from the skardet. The snow cover must have made the journey easier. I think the hillside is covered by scrub and boulders but all these were out of sight below my feet. My outward route included some steep hard snow which I was careful to avoid on my return. There was some interesting route-finding over the lumps and hollows to reach Andrevatnet. It nestles between Falketind and Hjelledalstind at the head of this pass between Vettismorki and Koldedalen: a great route in the clear sunshine, but not a long one because I stopped at the edge of the lake. The two beautiful sharp mountains have precipitous slopes leading down to the edge of the lake just waiting to dump snow and rocks on passing Yorkshiremen. This journey gave me views across Utladalen to the Hurrungane, with Vettismorki in the foreground far below me, and a good look into Stølmaradalen about which I was curious.

My final day out was probably the best. I spent five hours walking out to Sletterust, where I caught the bus to Øvre Årdal. The night had been warm, the snow was soft at hut level and I wore snow shoes all day except when attempting to negotiate a cliff. This must be an area of rough hills with innumerable lakes and a waymarked route. But with the depth of snow this May few of the waymarks were visible, the small lakes had disappeared and very steep soft snow or cornices surrounded the larger lakes. At the higher levels where the snow was hard, I found a steep slope that I could only just climb with snow shoes on. Some waymarks guided me over a cliff that presumably has a path in summer, but I found impassable at that point. Another cliff had no waymarks so I had the fun of finding a way down it. Only with ski or snow shoes could I have crossed this area. There was a layer of high cloud giving a flat light that did not show changes of angle or texture of the snow, which made the route-finding absorbing, quite a high enough risk for a solitary traveller.

This is playing in the snow. I was never extended and with the long hours of daylight, always had time in hand. And the sun shone!