YRC ‘Alpine’ meet

Picos de Europa

July – August 1995

Compiled by John Devenport

The Venue

The meet was based about 2km from Potes, about 80 miles from Santander on the east side of the Picos de Europa. The Picos are perhaps the finest and most compact set of ridges, pinnacles and gorges of hard carboniferous limestone in Western Europe and form the highest part of the Cantabrian mountain range in northern Spain. The Picos are split into three distinct massifs by deep gorges ranning north to south. Potes was an excellent base for access to the Central and eastern massifs and the Cordillera Cantabrica to the south. It is a region of Karst topography, underground rivers, resurgences, deep caves, gorges, steep valleys, sharp peaks and long steep rock faces. The higher mountains reaching up to about 8,700 feet are quite different to most other ranges visited by members of the club, being almost totally void of water, quite a problem in the extremely high temperatures that were experienced during our stay.

The lower pastures and alps above the gorges offered lush vegetation with abundant fauna and flora. Probably the liighhght of the trip was the particularly varied bird life, with many species not found in the U.K., most notably the birds of prey and especially the Griffon Vultures that were a memorable companions on many days in the high mountains.

The very steep sided valleys meant that reaching the higher levels involved a considerable slog, or use of the comparatively cheap telepherique from Fuente De, at the end of the Liebana valley. However, long queues were sometimes experienced for the descent to the valley at the end of the day.

Potes was a bustling, attractive old town, with plenty of character and characters. The Monday morning market was well worth a visit, where the usual range of market fare could be purchased, plus pigs, sheep, chickens and a wide range of other livestock. Shops and supermarkets provided a very cheap source of provisions and local produce. The local specialities included cider, a wide range of cheeses and chorizo sausage.

The Campsite

Our base was on the well appointed campsite ‘Las Isla Picos de Europa’ in Turieno, about 2km west of Potes, in Cantabria. (Tel: (942) 73 08 96). The staff made us feel most welcome during our stay, and many of us took advantage of the cooling pleasures of the swimming pool during the oppressive heat in the afternoons. Thanks must go to Alan Linford for finding us such a good base.

The Climate

For much of our stay, the weather was generally fine, clear and very, very hot, which meant that copious supplies of liquid needed carrying on a trips into the waterless landscape of the high mountains. Being so close to the Atlantic northern coast of Spain, the area was subject to mountain mists and summer storms.

Maps and Guide Books

The most useful guide book to the area was ‘Walks and climbs in the Picos de Europa’ by Robin Walker and published by Cicerone Press (£10.95).

Maps were somewhat more problematic, with many inaccuracies and deficiencies noted. However, probably the most useful were the following two maps:

1:25,000 Los Urrielles Y Andara (Macizos Central Y Oriental de Los Picos de Europa)

1:75,000 Picos de Europa – Mapa Excursionista (Miguel A Adrados)

Getting There

Apart from a long drive through France, most members travelled to northern Spain, either by Brittany Femes from Portsmouth to Santander, or by P&O Ferries from Portsmouth to Bilbao. The most convenient was undoubtedly the latter, which was only a couple of hours drive through spectacular gorge scenery to Potes.

The Attendees

Ken Aldred

John Medley

Steve Beresford

Alistair Renton

Christine Beresford

David Smith

Elspeth Smith

Ken Bratt

Alan Brown

Michael Smith

Helen Smith

Richard Smith

Fiona Smith

Cliff Cobb

John Devenport

Iain Gilmore

Sarah Gilmore

Derek Smithson

Mike Godden

Bill Todd

Marcia Godden

Juliet White

Alan Linford

Angie Linford

Martyn Wakeman

The Picos by bike by Martyn Wakeman

Watching the snow falling outside of my window, it seems strange to think that last August we were in the middle of a heat wave. Then to go cycling somewhere even hotter seemed to indicate the onset of cerebral dementia or something a mite more interesting than a week in Skegness!

I had a problem. How exactly was I to transport myself and a mere ‘sprinkling’ of gear to Potes, somewhere in Northern Spain. All cars seemed full and not fancying a battle with Spanish public transport, I decided to saddle up my bike and find an excuse for an extension to the holiday. This proved to be a smart move, as ‘The Picos by bike’ proved to be one of the most varied and interesting parts of my summer. After a few frantic phone calls and a gear dump somewhere in Yorkshire, my gear was on its way in David Smith’s caravan, and I could hop on the feny to Santander with my mountain bike loaded up with four days worth of dehghtful Soya mince and noodles together with lightweight biwi/camping gear.

Rather than extensive planning, I mused over a contourless Michelin map of Northern Spain and plotted a pleasant looking route around the coast and through the mountains to Potes. I would cycle as far each day as I fancied and biwi wherever looked suitable, to arrive just as the main YRC party descended on the campsite.

Cycling in Spain proved to be both a delight and a new experience. I stormed off the ferry and visited Catfo Mayor lighthouse for a view of the harbour before winding my way along the coast road to Santillana del Mar, a traditional ‘National Trust’ style Spanish village, full of nick knack shops and veiy photogenic. Continuing on to San Vicente de la Barquera for an afternoon nap, I had a fairly easy day finishing at a secluded campsite at Pechon overlooking a sea bay. This was gained by a steep winding road, which exercised low gears for the fust time.

The local Spanish holidaymakers seemed impressed by my Goretex biwi bag as I feasted on huge tomatoes, the dreaded Soya and noodles, and luscious nectarines. The evening was spent skimming stones before a well earned kip after the sun had gone for the day.

The next day’s target would be Cangas, which looked pretty easy on the map, but this did not show contours! Being a ‘green’ scenic road, it wound along by a river through a gentle gorge . Worried about dehydration and the weight of canying too much water on the bike, I had gone into camel mode, drinking all I could in the morning, and going for only two bottles on the bike. Just before lunch time as the sun blazed down, I was low on water, and needing a rest when a hill, or rather a pass, which did not register on the map. I thought I would combust, it was so hot! The exchange of pesetas for water and nectarines in a shop like someone’s living room at the top was very welcome, as was the fantastic free wheel down nearly all the way to Changes.

Some mountain biking up a rough stony track lead me to my tourist stop for the day, the Cueva del Buxu. These are supposed to be caves with wall paintings, but the exterior ones revealed nothing and the rest were held off by a locked door. With only the local flies for company, the main peaks of the Picos could be seen shhrrmeiing in the distance, insphing me to read more of the guide book and plan strategic bags for the two weeks ahead.

The process to cool down at the campsite consisted of a cold shower and a rinse of my sweaty rags before diying in the sun. The campsite was noisy, with lights on all night, and it even had the cheek to rain! An early start to gain miles in the morning cool before the sun became too hot became a wise move as today was the 40 mile climb into the mountains, from sea level passing over several cols to a high point of 1450m. A day to remember, a road winding around a river into a steepening gorge, eventually with walls of rock each side and peaks soaring above, beckoning to be climbed. The road was rough, pock marked with holes from rock missiles, and as the sun burned down in full anger, the tar melted with ‘Panaracer Smoke’ tyre marks visible in the worst patches. Lunch was a two hour feast of goats cheese, a whole fresh loaf, two litres of water and more nectarines in a strategically placed rural Spanish village.

Ever onwards, ever upwards was the motto for the day but the heat was incredible, with sweat pouring off and rests in the woods by the road necessary to cool down once eveiy hour. At last, the summit, or rather the first col, was gained followed a few more uphill bits before a tyre humming kamikaze dive down the other side, losing height very quickly, braking veiy hard at comers to avoid meeting my maker earlier than desired.

A lovely campsite with just some basic loos and the mandatory cold shower was found a few kilometres before Posada de Valdon. This was in a field sunounded by a tiny village out of a time warp, tumbling houses with no glass in the windows, women dressed in black, carts full of hay, with a backdrop of the harsh rock peaks of the Picos.

Next day, I could either ascend two more giant passes and come into Potes from the south, or try a Land Rover track which I had spotted on a large scale map. This track was said to be uncycleable, so with all the more reason to give it a bash I set off. The first pass was gained via a narrow and steep road out of Posada de Valdon which gave way to a modern road which led to the top. Engaging first gear I spurred my wheel off the road and onto the track, which would save road miles and prove greatly more interesting. The track did prove great fun, a monster slog, but I eventually arrived at the top at 1800m, with an awesome view of the massif and the valley down towards Potes.

The descent down the other side proved one of the best of my life, 800m height loss down rough Land Rover tracks (the latter one later ascended by the Nissan 4×4 tourist party) twisting and turning over the hard dry track, dodging boulders and pot holes. Stops had to be made due to the temperature of the rims decomposing the brake blocks, and even with oil/air front suspension, the descent was eyeball wobbling as I hammered down to the cable car at Fuente De before chasing a coach down to the campsite.

An amazing start to the holiday, a real adventure for me being in a foreign land and not speaking a word of the lingo and totally reliant on my bike not falling to pieces. Just feeling free to cycle where I fancied amidst glorious surroundings, sleeping under the stars and soaking in the real Spanish culture.

Ascent of Pico Tesorero (2570m) by Iain Gilmour

When Alan and Angie Linford suggested a look at a nice hill somewhere over on the left, two willing members, John Devenport and Ian Gilmour, joined the party. One hesitates to detail the first part of the trip, for from our campsite at 1,100 ft. we motored to Fuente De at 3,600 ft. and then took the cable car to 6,017 ft. Our cable car rose through cloud into brilliant sunshine and cool air, and the views over a cloud sea were reminiscent of flying.

The landscape around us was a vast arena of limestone peaks with jagged outlines like Sgurr nan Gillean, but of a warm golden colour. Between the peaks lay hollow depressions, called hoyos, with a strange almost lunar appearance. There is almost no vegetation, due to the altitude and over grazing by the few sheep and native rebecos (a small deer like animal with thin backward curving horns). The lack of water necessitates carrying two or three litres for a long day.

Some three miles from the cable car station, we reached the Veronica Hut at 7,600 ft. Near this hut, a band of different rock had weathered to expose thousands of fossils including tubular worms (crinoids) which had existed on ancient sea beds.

At this stage Alan casually mentioned that we would be alright, as he had a rope in his rucksack. Could it be that our look at the peak might require climbing gear, rather than spectacles or binoculars? There was no need to be apprehensive, for the South West ridge of Tesorero gave a splendid scramble over warm and dry rock with plenty of holds and no difficulties. Good grimping rock was the verdict.

Tesorero, 8,430 ft., is a splendid viewpoint for the whole of the Central Massif, and incidentally, is the junction point of three provinces, Asturias, Cantabria and Castilla-Leon.

Returning by the East ridge and viewing a spectacular rock arch on the skyline, we descended to the col at 7,700 ft. Two of the party made the twenty minute dash up Torre de Horcados Rojos by the walkers path. Our return to the cable car was memorable for the sighting of four Griffon vultures soaring on the afternoon breeze and thermals. Looking at the hills is a splendid pastime.

Pico de Grajal Abajo (2248m) by David Smith

Midway through the second week of the meet, Iain suggested that we have a day on the hills together, joined by Steve with an objective high above the tiny village of Lon. We had contemplated walking direct from the campsite but after second thoughts we went by car giving us a 520m start. Our tired feet were to be very glad of this by the end of the long day.

Lon straddles the hillside with picturesque old houses joined by steep rough concrete roads. Quite soon the road degenerated into a dusty track leading upwards, first through woodland providing shade from the merciless sun, then across two small newly cut meadows before opening out into a deep valley. A layer of cloud had to be passed through before we emerged back into the sunshine.

The cotton wool cloud totally obscured the valley. The mountain peaks look like islands in a billowing sea, the Cantabrian mountains contrasting sharply with the cloud layer. Our path followed closely the Rio Buron before opening out into a playa. Much of the vegetation was extremely prickly and no help in the ascent, the rough texture of the rock on the other hand was a great asset.

A little higher the river divided, we followed the course of the Canal de las Arredondas in which flows the Rio de la Vega in wetter times. The rocky canal took us to the deserted zinc and lead mines of Mina de las Arredondas above Le Campa. To gain respite from the sweltering heat we penetrated the workings for 100 yards or so, an arrow pointing the way out marked the junction of two passages. Later we discovered that Derek and Martyn had put it there during their search for water a week earlier.

Refreshed by the cool air we moved carefully up the course of the canal over steep and very sharp rock to the 2193m col. It was a mere 55m below the easily gained summit of the grand sounding named mountain, Pico de Grajal de Abajo. Had there been mist and had we walked 2 metres beyond the magnificent cairn, we would have plunged 2000 feet down the precipitous northern edge of the mountain into the Vega del Hoyo Oscuro. How different the mountain must look from the north facing side?

We enjoyed the views, we took pictures and we rested in the simshine before our descent to Lon. We had ascended 5,700 feet to make the climb, it was a great day in the mountains, but with good weather, goods views, good health and good company, what more could any man want.

Lone mountain climbing may suit some, but for my part let me share the experiences and the pleasures with like minded friends.

The Eastern Massif by Martyn Wakeman

Having already climbed several peaks in the Western massif I jumped at the chance to accompany Derek Smithson on one of his legendary expeditions. One ofthe greatest joys ofbeing in the mountains is camping or biwying up high where the grandeur and solitude ofthe mountains can really soak in. We therefore accompanied the ‘Last ofthe summer wine’ in Alan’s Landy to the village of Lon and departed on our way with biwi gear and enough food for three days, slapping greedy insects off our legs. We walked through the wo ode d lowlands to emerge onto a lovely grassy prominence, above which the peaks soared and the rest ofthe route could be seen. This would have made an excellent base camp for attacking this area if supplies could be helicoptered in.

Captivated by the scenery, we took a wrong turn following a stream bed until a huge chockstone blocked our way. The following ascent of a steep grassy bank, which felt near vertical, was hair raising and decidedly dodgy, especially with a big pack, but we soon retraced our steps onto the correct route. A climb through scree led to a lunch stop of bread, goats cheese and jam before continuing up the miners track to the Mina de las Arredondas. People who slogged up here each day deserve respect – they were hard in those days. Here was supposed to be a mine shaft where water could be collected from a drip in the tunnel roof, and we mused on the likelihood of this as we searched for the appropriate mine shaft.

After some exploring, it was time to don Petzels and grovel in the gloom for about 100m before finding a pool ofwater from which to :fill our bottles. This appeared to feed from melting snow, but was probably laced with whatever metal they used to mine. Cliffs rose above us, and the contrasting green o f the valley woodland could be seen providing a grand stance to spend a happy evening. Tails of past mountain trips were exchanged, and the wonder of snow shoes explained before a long leisurely tea finishing with Derek’s super luxury lemon crunch pudding. Two slugs appeared as we wriggled into biwi bags for a splendid night’s sleep, escaping the fug ofthe valley. When we awoke, low cloud swirled around, but after several brews it began to clear. Packs on, we climbed up to the ridge in the cool ofthe mist before leaving un-needed gear cached for the return. The ring of peaks that form the backbone of the Andora Massif provided an excellent days scrambling, culminating in the Morra de Lechugales (2444m), a towering prow of rock like a ships bow, with views ofthe western massif and the valley below. Traversing back, we discovered why the ‘La Rasa de la Inagotable’ had that particular name. Traversing around its rocky terraces, we avoided scaling it’s cliffs which would make an excellent day in their own right.

After regaining our sacs, we climbed La Junciana and Pico del Sagrado Corazon where the cast statue of St Carlos glimmered in the sun and vultures swooped overhead. An enormous wing feather fi:om one of the birds was found and added to our motley appearance, sticking out of my karrimat.

The descent down scree of Canal de San Carlos revealed numerous pot holes which begged for exploration, but time was pressing and we continued down the track. This is where the fun really started as the map and ground didn’t agree despite determined efforts to make them do so! After a bit of a fa£ we basically headed downward by wandering along tracks and paths through the woods towards the valley. Attempts at communicating in Spanish farmers resulted in confusion, but at least their dog didn’t eat us. Slowly the tracks merged into bigger ones and we found signs of life in a small village nestling in the woods.

When confronted by a local lady as to our activities, she seemed awe struck that we had visited the St Carlos statue and we extracted ourselves from her presence before we were any later home. A simple walkout back to the campsite then resulted and satisfied explorers could take off their boots, rest their feet, fill their stomachs and tell tales to their companions. Thank you Derek for your company and for an excellent two days!

Flowers of the Picos de Europa by Cliff Cobb

High summer is not the best time for alpine flowers, but we were very agreeably surprised at the wealth of flowers encountered, particularly in the higher, completely arid mountain areas.

A typical example; while lunching among the jumble of rocks immediately below the Veronica cabin we saw a beautiful example of campanula thriving in a tiny crevice, its roots no doubt penetrating feet (or metres) into the rock.

A further notable point was the occasional sudden change in geological formation, with a corresponding change in the flora.

Two special memories for me – the wide expanse of the ‘merendera’ on the edge of the Vega de Liordes valley, and secondly the superb steel blue thistles (eryngium bourgatii), lit be the brilliant sun, a colour I believe impossible to capture on film.

One disappointment was the absence of any gentians, presumably due to the predominantly calcareous rock, although other members did see trumpet gentians (g. acaulis) in one of the surrounding valleys.

List of flowers

| Achilles erba-rotta | Simple leaf milfoil |

| Arabis vochinensis | Compact rockress |

| Campanula | Various |

| Crepis | Hawksbeard |

| Dianthus | Various |

| Doronicus grandiflorum | Large flowered leopardsbane |

| Erica | Various |

| Eryngium bourgatii | Pyrenean eryngo |

| Geranium | Various |

| Geum montanum | Alpine avens |

| Iris latifolia | English iris |

| Linaria origanifolia | Toadflax |

| Lithodora oleifolia | Shrubby gromwell |

| Lithodora purpurocaerulla | Blue gromwell |

| Now Buglossoides Lunaris redivivar | Honesty Merendera montana |

| Parnassia palustris | Grass of Parnassus |

| Pinguicala | No flowers but typical pale yellow/green foliage |

| Petasites albus | White butter-burr |

| Potentilla cinerea | Grey cinquefoil |

| Potentilla fruticosa | Shrubby cinquefoil |

| Rhodiola rosea | Roseroot |

| Sepervivus montanum | Mountain houseleek |

| Silene acaulis | Moss campion |

| Viola pyrenaica | Pyrenean violet |

Although not identified, we almost certainly saw saxifrages and possibly androsaces among the many yellow and white flowers amongst the grass and undergrowth.

Rambling in the Picos by Alan Brown

It was disconcerting to discover back in March that the Plymouth / Santander ferry was fully booked throughout July and August needing space for caravans or trailers. However, the longer Portsmouth to Bilbao ferry fare included cabin accommodation so this, coupled with the shorter motoring distance for Northerners, made the cost roughly the same. A good motorway between Bilbao and Santander enabled us to reach the Potes campsite in three and a half hours.

Derek wanted to be off on a three day trek as soon as possible, so day one came with a 05.30 reveille. The village of Lon, some ten minutes west of Potes was clearly asleep as four walkers and two backpackers set off up the River Buron heading for the Canal de las Arredondas. Best avoided during veiy hot weather intoned the guide book, but veiy hot weather was a prominent feature of this meet, so gaining height early had a special appeal. It was our first exposure to typical Picos de Europa terrain. Steep-sided ‘dolomite-shaped’ mountains with jagged ridges, seemingly inaccessible in all but a few places. The steepness of every approach brought the ridges closer so we were constantly aware of the grandeur of our surroundings.

Day one also gave us an early awareness of the profusion of alpine flowers and plants, which in turn, attracted the greatest variety of butterflies most of us had seen, details of which are listed later. The backpackers slowly pulled ahead whilst the rest of the party absorbed the spectacular mountain scenery of the Arredondas, an experience we were to enjoy throughout the next fortnight.

At 1,200 metres, Las Cabanas provided an acceptable turning point for our first day, the nine hour trek coupled with the heat being a good initiation for the days ahead.

The crowded campsite reflected the national holiday period, yet apart from the routes served directly by the cable car, we met very few kindred spirits on the hills. On two occasions we attracted other walkers who mistakenly believed we could be relied on to finish a promising route in an orderly fashion. Aniezo, 10 kilometres east of Potes was the starting point for a steep ascent to the Ermita de Nuestra Sra de la Luz – a hilltop church a couple of hours from the village – where we casuahy noted a party of five Spaniards and two Swedish walkers. The circular route continued north-west along a good path, which then curved sharply south, disappearing into a steep heavily wooded valley. Whilst reasonably sure of our general direction, the scarcely discernible path soon disappeared altogether, and it was at this juncture that we discovered the Spaniards and Swedes confidently attached to the rear of our party. The angle of descent called for much hanging on to trees and branches, but the thick undergrowth eventually gave way to open meadows, where recently harvested hay allowed an easier stroll down to the village. Profuse thanks from our continental friends ended another good eight hour day.

The Canal del Embudo is traversed by climbing 950m from the cable car station at Fuente De, via 38 unforgiving hairpins, warned the guide book. The valley below and the vertical south wall of La Padiorna to the north provided breathtaking views, the torture ending with arrival in the Vega de Liordes, a high alpine meadow surrounded on all sides by high mountain ridges. A circular route home over the southern ridges looked altogether too demanding so we headed due north encouraged by a taciturn Scot who knew the area and understood our intentions. Here again we were joined by a middle aged couple, dressed for an easy day in the country, who were dissuaded from the southern route. They were a game couple willing but not used to the scrambling necessary over the Sedo de la Padierna and the Canal de Santa Luis. Their inadequate water supplies caused further delays but the top of the cable car was reached in time and our guests happily plied us with cool drinks before the drive back to camp.

Whilst many days were spent on the arid limestone area to the north west of Potes, some time was enjoyed in the more varied area to the south and south-west. Here the limestone masses were replaced by shale valleys with large whaleback ribs of limestone forming higher rock faces above. A number of isolated hamlets and small villages depending upon agriculture were another difference from the barren area above Fuente De. It was two of these villages which we visited, taking the road by tunnels driven through solid rock to bypass some very steep limestone faces. \on a shelf at the head ofthe valley, the further of the two villages appeared to offer an ideal holiday situation for the artist. A small church, an inn and dehghtful pantiled houses had an air of restfulness in the mid-afternoon sun. A small group of children played quietly. Perhaps it is uncharitable to suggest that their lack of boisterousness was the result ofthe high temperature. The variable bedrock supported a wider range of flora than the solid limestone to the north, for the shale provided not only a different chemical base but it also appeared to retain moisture within the rock. This resulted in both calcareous and acid loving plants as well as large trees which were completely absent from the former area. A couple of footpaths winding along the upper reaches of the valley gave us a series of platforms for views ofthe villages and lonely farm houses, whilst the village inn was a welcome halt before rerarning to the campsite.

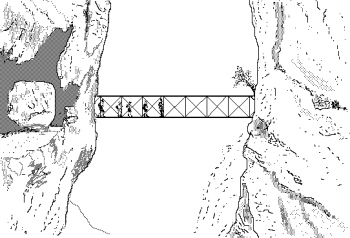

Finally, and with the assistance of a four wheel drive car taking us over spectacular mountain country to the starting point at Cain, we traversed the Cares Gorge – Spain’s answer to the Grand Canyon. Much smaller of course, but very impressive, albeit the most popular tourist route in the whole of the Picos de Europa.

This was a fine Alpine Meet, where few actually missed the snow and where exposure to only a small area of Picos de Europa territory wetted the appetite for more.

Butterflies And Moths Observed In The Picos by Alan Brown

Apollo Large Copper

Blues – various * Large Fritillary *

Brimstone Marble White

Burnett Moth Orange

(Six spot) Underwing

Camberwell Painted Lady

Beauty Peacock

Cleopatra Ringlet

Clouded Yellow Scarce

Common Heath Swallowtail

Common Heath Tiger Moth

Gatekeeper Tortoiseshell

* There are 44 varieties of Fritillary and 42 varieties of Blue. The author regrets that precise identification cannot be confirmed.

A Long Day In The Picos by John Medley

It is traditional for the alpine meets of the YRC to produce at least one mountain sequence sufficiently diverting and eyebrow raising to require individual report. This time it fell to the Old Gentlemen to provide it.

From El Cable, the top of the telerifiqo above Fuente De, it is a pleasant excursion to Pena Vieja summit, whither four of the maturest Members on the meet made their way in the mounting heat of the morning of Saturday 29 July, one goes westerly up the path towards the Cabana Veronica, then hard right up the gully to the Col Canalona and back eastwards along the ridge, then bearing left up the slope to the top of the mountain. It was leisurely and pleasant; lunch on the summit.

Back to the col, where thoughts arose about an alternative route back. Although it was understood that precise iirformation could be extracted from the maps, it seemed reasonable to consider dropping down to the road through the Aliva area whence back to El Cable in good time for the last cable car at 21.00 hours. Best available advice (in imperfectly understood Spanish) was not to go straight down from the col but to follow on below the ridge a little way in a northerly direction and pick up what traces of tracks there were. This worked quite successfully; there were numerous cairns about, which tended teasingly to discontinue in awkward places but which were eventually connected with a large painted snow-pole in the middle of a heavily cratered area, from there the route seemed to go slightly uphill, then downwards again, following still capricious intei-mittent cairns and treacherously be-pebbled rock that at one point precipitated a damaging tumble.

Eventually the slopes ran out to an edge, with the valley floor and road in tantalising view less than 100 metres below, but here progress stopped, one member of the party being unprepared to be committed to the only possible route that presented itself. So back to the col; there should still be time to climb up, cross the ridge and catch the last cable car.

The snow pole was regained in reasonable time, but then there was trouble. Indications of paths lead in all directions, but one (uncaimed) was chosen which approached the high ground to the north, perhaps remembering the difficult terrain opposite and the original high level detour from the col. The ridge was eventually gained but a considerable distance from the col, with many obstacles between. It took a long time to come down again and work across, eventually airiving at a little snow slope from which the col was known to be readily accessible. But it was already nearly dark, with cloud building up in the high valleys below. All hope had gone of making El Cable in time; the aim now was to get down to the Refuge de Aliva and telephone reassurance before anybody noticed a certain empty Landrover.

In vain! The party admired the lights of ‘civihsation’ just below the mist and stumbled, first into young campers playing games with lanterns on poles, and then into a parked Gar da vehicle that had been sent to look for confused old gentlemen reported lost in the mountains. The driver was veiy kind, but made it clear geriatric escapades should not be exacerbated by attempting to explain in Spanish. Most of the meet seemed to have turned up at Fuente De to assist; it was a happy occasion though embarrassing to some and by 0200 hours everybody was in camp and in bed.

Bird watching in the Picos by Alan Linford

Bird watching in the Picos can seriously damage your detennination to achieve the days objective. There is so much to watch that delays are inevitable.

Once again, Ahstair’s series of mishaps provided a benefit, his early morning arrival having overnighted under a hedge with a broken cycle, delayed a start to climb El Cvernon – a vantage point to obtain an overall perspective ofthe Central and Eastern Massif. Not a pleasant walk in the heat of the day, but rewarded with gentians on the alp, a first view of a Griffon Vulture and, our return, a close view of a pair of Black Woodpeckers in the holmoak forest.

The walk down to San Aniezo is awful, but again a reward with a veiy close view of Short Toed Eagle – we did not know what it was at the time and had to consult the guide book to confirm the sighting. This proved to be the start of a bounty of bird life: Linnet, Red Kite, Black Kite, Black Redstart, Corn Bunting, Snow Finches, Wheatears, Choughs, Juvenile Robin, Buzzards, Eagles, Rock Thrush, Hobby, Juvenile KestreL Tree Creepers and Rock Thrush.

We searched extensively for the Wall Creeper but failed to spot it, a lot of screeching as the Hobby swept across the cliffs but no sighting.

It was the Raptors that held the attention, the Egyptian Vulture and Eagles only students – the master of the air is the Griffon Vulture. In the Cares Gorge we counted twenty – ten circling in a small valley – then approaching closer a sighting at 200 metres of a group of Griffons feeding on a carcass. The carcass had been torn into two with a group on each, fighting between themselves, the group hierarchy clearly visible. It is not only the huge wingspan which attracts the attention but the depth of the wing needed to provide lift for the giant body (and ugly head). On the traverse of the Pena Remona (2,247m) we were above a group of circulating Griffons, again at close quarters. We witnessed the efficiency of this large wing, the control movements of the primary feathers and the air flow over the wing the lifting of the feathers in the depression zone. What a maivel of natural engineeiing.

Despite trips into woodland areas we leave until our next visit sightings of Capercailhe, Tree Pipits, Owls and Nightjars: all reported in the area.

Peaks and Passes – Two people’s adventures in Northern Spain by Bill Todd and Juliet White

You couldn’t move for Yorkshiremen in Spain this summer. Apart from when we visited the camp site and were hospitably entertained, and when we walked with Ian and Sarah we met them in the supermarkets, on the cable car, in the car park and several lots in the Cares Gorge. This was our first days walking after arriving on the meet a week late and will no doubt have been competently covered by other members.

The following day was uneventful; we drove to Fuente De and because there was cloud on top went for a walk up the track to Collado de Pedabejo. Returning from this at lunch time we took advantage of improving weather to go up the Teleferico. We hadn’t been there very long when cloud came down again after a tantalising view of the big peaks. I can foresee the embarrassing question at my next slide show, “Did you climb it?”. “No”. “Why not?”. “Bad weather”. “It looks alright on that photo”. “Yes but it got misty”. “A likely tale”.

This was Wednesday 2 August and Juliet insisted on treating it as a rest day because we hadn’t climbed anything. So the next day we went up the highest peak in the Cordillera Cantabrica.

On Saturday 5th we did a classic walk, the circuit ofthe Pena Remona. This involved following our Wednesday track right up to Collardo de Pedabejo and crossing it into the Vega de Liordes. This is a dehghtful green basin with horses and campers and after walking across it in poorer weather we descended the famous zigzags from Cohardo del Embudo.

Juliet did a nature walk on Sunday with Teresa Farino, the local expert, while I conserved my strength to climb a peak. So, 10.25 a.m. found us leaving the top of El Cable in good heart to attempt Tone de Los Hocardos Rojos. But the weather got worse and worse, and at the zigzags it started raining and blowing, so we scuttled into the Cabana Veronica for hot soup which proved to be a life saver. By the time we’d finished our soup (100 pesetas per cup) a queue had formed in the hut entrance so we had to go out into the storm and eat our lunch behind a boulder. An attempt to explore towards Hocardos Rojos met with more wind and rain in our faces so we beat a retreat.

We heard from neighbour, Dolores, about a fatal accident on Sunday 6th involving people from Santander. We gathered that a land rover had gone over a cliff while on the way to a fiesta on top of a mountain. This was our second day with Mike, our host and guide, and we left it to liim to show us a good day out. Driving through the Vinon, we parked his land rover under Pena Jumales and set off up the track to Madaja Trulledes. On a bend we met three fellows. It turned out that one of them was the son of the man who had been killed and he had come up with a friend and a local shepherd to see the actual location of the tragedy. It seemed that the long wheel-based vehicle had not been able to take the bend in one, and reversing to get round, had run down the veiy steep track and over the edge before the driver could re-engage first gear. After due commiseration we went on up to the Majado where we had lunch. After this Mike took us up a very steep pass, the Collardo de San Carlos to about 2000 metres, while I stayed on the pass to take photographs. The return journey saw better weather and we saw a wall creeper and a guinea fowl.

Friday August 11th was the day your idle scribe got his second and third summits. Mike was our guide again and we motored through Hermida and turned left to the village of Beges, where we bough cheese. After this Mike took us over the north-east shoulder of Agero Bis (1349m) into a misty wood. “I’ve not been this way before” he said as we picked our way through the beech trees, “but we should come out on the ridge you can see from the guest house”. Of course we did and came out of the clouds finding some limestone to scramble on before hitting the top and crossing to the slightly lower Agero at 1330m Today was notable for the weird shapes assumed by the cloud sea below us and for the view of Pena Ventosa across the Deva valley. Mike knew a grassy descent route to Beges.

Pena Ventosa looked interesting and Mike advised us to tackle it from the south east, so the following day, Juliet and I drove to the nearby village of Solarzon and walked up into the fields. Yes, the peak looked reasonable; between the steep south face and an area of limestone slabs was a harmless looking grassy gully which led onto the ridge, from where it may have been possible to tackle the steep final tower. So above an awkward stretch of bracken and broom we climbed a scree slope then got onto our chosen route. What a shambles it was. Scree under grass and more broom, loose rock, Juliet was in front. “What do I do if a hold is loose?” “Put it to one side and see what’s underneath it” I replied. As these things do, it seemed to be going to level out in a few yards but it never did until we struck the ridge some time after 2pm Westward was the summit tower, looking a bit like Sgurr Alastair from Sron na Ciche, and eastwards was the ridge looking a bit like Crib Goch. Over lunch in the hot sun we discussed what to do next. It was too late for a serious attempt on the summit and Juliet was not keen on reversing what we had just done, neither was I. So we took the only choice left and followed the east ridge just below the crest until we came to a green track sloping through the slab area. This was evidently the normal way up to the ridge because we found a toffee paper on it. We were glad to get back into easy ground but not too chuffed to see a couple strolling along the ridge beyond where we had left it in bathing trunks and bikini respectively.

Sunday 13th was our last day and Mike engaged our interest by mentioning a “user friendly crag”. This was on the lower slopes of Agero and has the same name. Here we spent a pleasant, if roasting, day climbing on V. Diff. rock and abseiling. A good finish.

For our stay, Casa Gustavo proved quite wonderful, at £25.72 per person per day full board, with all of the beer or wine you wanted at the evening meal which was very good; 3 course, but seived quite late (about 9 p.m.) for an early bed and early start. Continental breakfast (plus cereals and fruit) was 9 a.m. but we could get it earlier on request. On one such occasion, Mike came running out with our packed lunches as we were driving away.

A great big pile of stones – Pena Prieta in the 80’s by Juliet White

Picnic lunch had been among Pena Prieta’s cast-offs. Ten to twenty foot lumps of nut brittle (sorry, conglomerate) thrown across an upland lawn divided by tiny streams and known as ‘The rock garden’. A leisurely lunch. The two small boys in our party and Bibi, the dog, entertaining us with bouldering fun and games. Towards two o’clock we said goodbye, six going up to the lake, and Bill, Mike (our host and guide) not forgetting Bibi, who takes a mountain climb as exuberantly as your average city pooch would take a scamper around Clapham Common, heading for the top of Pena Prieta.

I’ve never climbed on such user-friendly rock as the first stretch. Hand-sized pebbles set in rock with pebble sized hollows for your feet. Thus we set off up the north-eastern ridge of our mountain. It should have been a piece of nut-brittle cake, but it was hot, hot siesta time. Did I eat too much lunch? Is this altitude sickness? I didn’t like these reminders that I can’t stay twenty-five for ever. So concentrate on getting those heavy arms and legs to take you upwards. One tricky exposed neck to negotiate and then the gradient eased.

“That was the hardest bit. The rest is straightforward” said Mike. So with my usual inward reservations about what an experienced mountaineer describes to me as “straightforward” I contemplated the unbroken upward cmve of grit and gravel ahead of us. Ugly and gritty underfoot, but what views were starting to open up. Cordillera Cantabrica stretching into irifinity in three directions. My very first view of one of those much read about mountain ranges. Turn round and at our backs stands the craggy backdrop of the Picos. But keep going, there’s walking to do, a 6.30 rendezvous at the Land Rover with the rest of the party, and many more stony delights ahead.

Soon we were at the trigpoint at Mojon de las Ties Provincias (2497m), the boundary marker for Leon, Cantabria and Palencia. Time for drinks and to take in at greater leisure this glorious view of the world from 7000 feet plus; the Riano reservoir, crazy limestone fault castle, real forests dense enough to shelter bears, clouds in the valleys, and the great wall of Atlantic cloud to the north that we saw so often during our stay in the Picos.

The way ahead, the other half of the horseshoe leading to Pena Prieta turned out to be a long trail across black and rust coloured angular stones like ballast on a railway track, ugly and laborious to trudge on. ‘U faut souffrir pour voir le bel”. Forget the pebbles and look at the valley clouds and the hills to the hills east glowing pink and gold as the sun gets kinder.

Peace of mind is a good thing when you’re climbing, but at some stage on the way up your mountaineering apprentice has to summon the courage to ask the question “How do we get down?” “Two ways really” said Mike. Can you scree run? It would be quicker and more fun. I’ll hold your hand.”

Well if Mike and Bill thought that I could cope, pride dictated that I should smile gamely and be prepared to tackle yet another first in my mountaineering apprenticeship.

Not much time to linger at the top of the Pena Prieta. Similar vast views as we’d seen en route, except that now we could peer down almost vertically to the Rio Frio summer pastures, where our walking had started, to the Rock Garden where we had picnicked, and to the lake, where we could see the rest of our party, splashing, chasing and bathing.

I did do the scree run. Teetering like a toddler, this granny lurched through the clattering pebbles holding Mike’s hand, while the dog scampered around us and descending muscles starting to plead for walk’s end. Bill and I finished the gentler gradients of the scree so slowly that Mike had had time for a swim in the lake before we caught up with him.

Then there were no more stones. Perfect green pasture with delicately positioned musk mallow, bell flowers and purple merendas. Grazing cattle, goats and sheep as before. Just one thing had changed. While we were up on the mountain, the easy mile or two from the Land Rover to the picnic spot had suneptitiously quadrupled. Honest they did. It’s not only Einstein who could tell you about relativity!

Picos Experience (5 August 1995) by Bill Todd

The rain in Spain falls mainly in the hills,

We found out yesterday on our descent. The grassy plateau bright with sinuous rills,

And varied with the occasional mountain tent Gave onto a steep zigzag down and down

To reach the Fuente valley far below. We took it cautiously with careful step,

Like Agag placing fine each heel and toe.

When suddenly the heavens opened wide,

‘Twas more than just a little summer shower.

On narrow path we could not turn aside There wasn’t even room for a wild flower.

So exercising all our craft and skill,

We doffed our sacks and took out our cagoules And donned them on that steep and stormy hill.

The rain then stopped, we felt such awful fools.

Multi-day tours in the Picos by David Smithson

This was my first summer meet in Continental Europe with the YRC. Martin Wakeman documents of an initial two day traverse of the Eastern Massif, but after that I was left to travel alone. Should I “read” something into that? My routes were a four day traverse of the Central Massif and four days pottering around Vega de Liordes, an alpine meadow at a height of just under 2000m, where horses and cattle graze all the time and where Spanish chamois, rebeccos, have a daytime feed. A very lovely place to be, without too many visitors and much cooler than the lower valleys.

After a hard journey from El Cable to Bulnes, i.e. from the south to the north of the mountains of the Central Massif, I had an exhausting day going through the Cares Gorge and up the road to Cordinane, all in intense sunshine. Bulnes has no road access, but two dehghtful little gorges, an auberge, a bar and a camp site. The Cares Gorge has the same lack of real atmosphere as Dove Dale on a bank holiday, but on the next day I enjoyed great variety. I walked out of Cordinane with four litres of water because I could not guarantee getting water in the next 24 hours. I had cooked my evening meal by the public fountain and bivouacked just out of town where the path approaches a serious looking cliff This is a region of serious looking cliffs and many of them look more and more impossible the longer one looks. I settled to sleep hoping the mist would get no wetter and that the route would show itself in the morning. The route appeared as a path ingeniously winding up and around the cliff. This was followed by a dripping birch wood and then an alpine meadow with at least two tents and no signs of water. I sat and read for a while hoping the mist would clear and when it didn’t, I took the straightforward Canal de Asotin. This led me above the mist and through a series of alpine meadows with their multitude of flowers and butterflies on bright green grass, which contrasted to the stark grey rock. The day finished fairly early with my arrival at Vega de Liordes with an almost perfect bivouac site, martin Wakeman had given me some instructions on bivouac sites and cooking muesli, which will perhaps change my life style. I had made a simple bivvy bag from some cheap waterproof breathable nylon and first used it with Martin who is a bivvy addict. I didn’t use my tent in the mountains at all.

Later, I discovered that the journey from El Cable to Vega de Liordes is not so easy or simple as I expected. This land of shaip rock with innumerable holes, hollows and gullies is difficult to traverse, but most routes have occasional cahns. The caims appear to comfort one when on a route but are not so obvious and frequent to allow relaxation. I met a Dutch couple who followed caims and found they had transferred routes without noticing. On my first visit to Liordes I had made an attempt on Tone de Salinas with the idea that I might be able to traverse onto Tone del Hoyo de Liordes. I was distracted by some caims and struggled up a scree slope which seemed to lead nowhere except a chockstone. On my second visit, I walked to the top of an adjacent pass, Collado de Remona, but found no sign of a recognised route up Tone de Salinas or up Tone Pedabejo. I enjoyed a scramble across the rocky mountain side to the bottom of the ridge I originally intended to tiy before the cairns redirected me. I now felt the cairns might be pointing to this ridge, but after some easy climbing I came to a pitch beyond my courage and descended to have lunch at my bivouac. Torre Pedabejo had appeared impossible fr om the pass, but now I saw a back door up the grass slope near my camp. It worked, and after getting to the top of Tone Pedabejo, I managed to traverse back onto the next peak in the direction of Pena Remona before the mountains became too difficult. There is obviously a lot of fun to be had playing on these mountains and the guide book shows that there are recognised routes up for those who demand success. After this I made a visit to the hut on Collado Jermoso which is magnificently situated. There, a lady told me that the cows on Vega de Liordes have a reputation for eating tents, clothes and provisions and she considered I’d been veiy lucky having no problem There is a cabin where people can leave gear safe from the cows. She also told me of the notice at the telepherique up to El Cable warning one of the existence of bears.

Needless to say there are lots more walking routes of quality and plenty of mountains other than the ones I was on, but for much of this I would recommend having a companion. I totally neglected the lower valleys and would suggest cooler weather would make them more pleasant and the use of a car make them more accessible. The sharp rock made the fingers sore but provided an unbelievable friction grip for the feet of anyone who does not usually climb in Skye or similar places in Norway.

On my penultimate day a flotilla of cigar shaped alpine storm clouds appeared and I took the precaution of sleeping in a hut. There was no storm where I was, but the evening mists were worse than usual, and for my final there were clouds on the high moiuitains and a cold wind that made me think about getting gloves out. As I started to descend the intermiable zigzags to Fuente De, a rebecco stood on a promontory watching me leave, a vulture soared high above the spires of rock, around me were flowers and butterflies, and beside me a line of impassable cliffs.

Tour 1

El Cable – Horcados Rojos -Vega Urriello – meadow above Bulnes

Bulnes – Cares Gorge – Cain -Mllside above Cordinanes

Asotin – Vega de Liordes

Vega de Liordes – attempt Tone de Salinas – Fuente De

Tour 2

El Cable -Colladina de las Nieves – Vega de Liordes

Vega de Liordes – attempt Torre de Salinas – Tone Pedabejo -Liordes

Liordes – Sedo de la Padierna -Pico de la Padierna – Collado Jerrnosa – attempt Tone del Llambrion – Refuge Diego Mella

Refuge Diego Mella – Sedo de la Padiema – Fuente De

Three days into Two by John Devenport

The best laid plans often need revising, particularly in mountainous areas such as the Picos de Europa, as Michael Smith and myself found out. Neither of us had ever been to such a mountain landscape as the incredible limestone deserts of the upper parts of the Picos, with then peculiar features and absence of water, and it was evident that navigation in anything other than perfect visibility could be a major problem. The object of our planned three day trip was to see some of the sights of the Picos, namely the Cares Gorge and the main symbol of the mountains of this part of Spain, the Naranjo de Bulnes.

Helen transported us to the start of the Cares Gorge at Cain, an incredible car journey in itself, with the road at one stage seemingly petering out in a farmyard, but it eventually led into the start of the gorge. After a welcome cup for coffee at a small cafe, the two of us set off in overcast weather into the deep, deep gorge forming an amazing natural banier around the western / north-western edge of the Central Massif. The path is an amazing feat of engineering, cut into the sheer sides of the precipitous rock walls, following the line of an aqueduct dating back to the 1940’s. Two bridges across the gorge provide spectacular viewpoints to the river many, many feet below. The rim of the gorge and peaks rising into the clouds, were many, many feet above. It is evidently a very popular route, as it is veiy easy walking along the mainly level path, and about half way along, after lunch and an excellent view of an eyrie, with an eagle feeding its young, we opted for a steep descent down a scree path into what we though was the bottom of the gorge, to get away from the crowds. Even when we reached the low point, we were still a considerable distance above the river.

Interest in the gorge decreased as it opened out somewhat as we approached Poncebos, but our destination for the day was Bulnes, so we turned up a side gorge, the Canal del Tejo that lead us steeply up to the village. By the time we reached the ancient hamlet, the clouds were right down and it was starting to drizzle. Accommodation was found in a dortoir attached to one of the three inns (not bad for an almost deserted village only reachable on foot!). Although it was now quite wet, it was still warm, so we sat outside the bar, eating the standard platter provided by the inn to everybody requiring food, namely ham, egg and chips. We really pushed the boat out, (well, we were on holiday) and also had cheese, wine (lots), coffees (several), and then breakfast the following morning, but despite this excess, got change out of £30 for the two of us , including the accommodation. If only Swiss mountain huts were as cheap as this!! Whilst sat in the bar, we exchanged tales with fellow travellers from several other parts of Europe, and were also joined by the local mules which came to see what was going on.

After a comfortable night, we woke to find that the cloud was even lower, the drizzle harder and there was absolutely no wind. So no chance of a quick improvement to the weather. After spirming out breakfast as long as possible, we decided not to tiy and find our way to the Urriellu Hut, under the Naranjo de Bulnes, because of potentially veiy serious navigation problems through inhospitable terrain in minimum visibility. Even if we did reach the hut, there was no guarantee that we would be able to get back to

Fuente De the following day, so opted to return via a lower, but much more circuitous route via Invemales del Texu, near Sotres and the Valle del Duje, in the cloud for virtually all of the way, with only tantalising glimpses ofthe peaks and precipices above. The first part of the route followed a veiy narrow path through dripping vegetation, rather like walking in a sauna. I wasn’t sure how effective the waterproofs were in such high humidity; the few Spaniards that we saw used capes rather than cagoules. We’d heard all sorts of tales about the inaccuracy of the Spanish maps, particularly where paths and buildings were concerned, but we had no problems, managing to follow the vague path and locate every building along the initial part of the route in the thick, swirling mist.

From near Sotres we turned south along the jeep track, which proved to be a most interesting walk, passing through the deserted hamlet at Vegas del Toro, then across a large flat meadow at Campomayor, where we had excellent views of a pan of Egyptian vultures, many other birds of prey, large numbers of horses, a lxinning track denoted by a line by numbered stones, and most amazingly of all, two pahs of goalposts, high in the mountains and literally in the middle of nowhere!

A quick descent down the jeep track brought us into Espinama, just in time to buy some much needed drinks and ice creams, before the last bus arrived to transport us, a day early, to the camp near Potes, much to the surprise of those in camp basking in glorious sunshine. Of course, the next day was another glorious hot, clear day, such is the way in the mountains!

A fleeting visit to Naranjo de Bulnes by John Devenport

After the disappointment of not seeing the Naranjo de Bulnes at close quarters on my multi-day trip, I decided to try to make a quick visit from El Cable to the Uiiiellu Hut, nestling in a privileged position beneath one of it’s great walls. Setting out in clear and shghtly cooler weather, I was accompanied almost as far as the Veronica Hut by Michael and David, but they had other objectives for the day, so from then on it was a solo trip.

From the Horcados Rojos coL it was a traverse eastwards then a steep descent down the broken, slabby slopes following the line of fixed cables, complete with highly frayed wire strands, which proved to be more of a lrindrance than a help. The long descent took me into the first of two huge hoyos (hollows), linked by a vague, intermittent path, which confirmed my concern about potential navigation problems in such awkward terrain should the visibility be less than perfect, and probably justified our change of plans during our multi-day trip.

A group of about six rebeco caught my attention crossing the barren slopes of a hoyo; it certainly must be a hard life eking out an existence in such inhospitable terrain. After the second hoyo, a col is gained by a steep step, from where the massive face of the Naranjo de Bulnes suddenly comes into view. The short walk down to the Uirielfu hut took ages, with many inteixuptions for photographs of this imposing mountain. The large modem, hut was thronged with visitors admiring the spectacular setting.

Time was getting on, and it was quite a way back to El Cable, so I turned my back on the Naranjo, with only one or two wispy clouds high in the otherwise clear sky. Then in an instant all my worst fears about navigation problems were realised. From nowhere, I was suddenly engulfed in thick cloud just above the hut, and thought I was going to have real problems getting back in the mist. Fortunately the mist cleared as quickly as it arrived, and the return to El Cable passed without further incident, but with added interest of a long scramble up to the final col at the side of the fraying cables.

The trip was a fitting end to my visit to the Picos, an area of quite unique mountain landscape, but it also seived as a sharp reminder of the potential difficulties the unwary traveller could find themselves in such inhospitable terrain.

Archaeology in the Picos by Michael Smith

The objects of the Club include Archaeology and this was not neglected despite the majority of this report concentrating on the mountaineering and natural history aspects of our visit to the Picos de Europa.

A visit was made to the caves at Ribadesella on the coast. In the Cueva de Tito Bustillo the control of public access to four hundred visitors a day protects the prehistoric cave painting. This was far higher number than most other controlled caves: Altamira allowed only 30 and visits had to be booked years in advance. Several doors along the caves blasted modem entrance tunnel maintained a steady temperature of 13°C and humidity of 98%. A path of 540m through the original cavern leads to a junction and a prehistoric living area. Here, low on an overhanging wall, is painting of a horse which despite damage by flooding remains clearly visible. The solid shape is a dark red and, for me at least, suiprisingly large at perhaps two metres long.

A little further on is an area containing several paintings. Stag, Mnd, several horse, reindeer and possibly something like a cow. The largest horse varies in colour from sienna to purple and black others are simple outline drawings. In some engraved lines emphasise the colour.

It was interesting to compare these painting with the rock outcrop engravings seen at Alta in Norway on the 1992 meet. Those were dated at about 6000 years old and were carvings, some of which were painted in an red ochre colour.

The Tito Bustillo cave paintings were created over a period between 15 and 20 thousand years ago.

The main cavern contains plenty of decorative rock features throughout its length. Colours range from the pristine whites through ivory to greens and reds. The calcite features are varied and impressive as the cavern is wide and tall. The streamway is now some twenty metres below and visible in places.

A short drive away, high on a hill side are a couple of prehistoric rock carvings. The information we obtained about them was sketchy. They are about a metre tall, cut into a slight overhang above a small ledge on a ten metre tall grey limestone outcrop (Pena Tu) on a ridge. Now protected by an iron cage they previously suffered the addition of many adjacent modern carvings, mostly crosses. The carvings are Bronze age or Neolithic and may be funerary or sacrificial.

Much further to the West, inland from Navia on the crest of a ridge was the Castro de Coana, probably the best preserved of the prehistoric Asturian ‘towns’. Occupied in the late Iron Age and early Roman period it is a well fortified habitation with very solid stone walls, circular, oval and rectangular buildings and large stone troughs. Served by a long aqueduct the village was supported by mining, transport and working of gold.

Under Roman occupation the Asturians provided troops for many parts of the empire including Hadrians Wall. They must surely have noticed a marked change in the climate there compared to their homeland.

The proximity of the Picos to the nigged coast, towns and unspoilt villages of Cantabria and Asturias means that there can be much more to a visit there than walking, climbing and caving. The Celts settling in the North, the Romans taking two hundred years to dominate the area (though leaving the Picos well alone), Visigoths taking over Galacia, Christianity with its monasteries and then Industrial Revolution have all influenced the area.

Memories of the Picos by AB

Friendly people at the camp site who went out of their way to be helpful.

A young dog, apparently dying of thirst, being refreshed in best John Wayne style, from a bush hat full of water.

A middle aged couple who were so impressed by the navigational skills of YRC members that they insisted on buying the drinks at the cable car station.

An ex-president who insisted that pear peelings and core soaked in sardine oil was part of the normal diet.

The entrepreneurial skills of a young guest on the meet who could run a second hand car business during the course of a restaurant meal.

Two members who provided a large number of locals with a new spectator sport: – leg breakage repair watching.

A local member of the Guardia Uncivil who seemed to think that three score years and ten equates to old age.

Members wives who provided hot soup to a group who arrived back at the camp a little late, following a slight geographical error. (Incidentally, this was the same group who so impressed the middle aged couple noted above!)

Two young members who reached the campsite on bicycles. What can we do to win this battle of one upmanship on our next meet?

The worred looks of passengers on the ferry who overheard two naval architectural members discussing the gross instabihty of the ship.

Female persons on the meet who appeared quite normal and, in fact, were excellent company. (I realise that this statement may cost me my epaulettes and sword.)

Four gourmet members who couldn’t tell the difference between ham and tinned tripe.