Minor Rambles in Romania

George Spenceley

Over a period of more than thirty years and numerous visits my wife Sylvie and I have developed for Romania a kind of love-hate relationship: love for its varied sceneiy and its rich peasant culture, hate for its inefficiency, its corruption and ciime. While we had motored, walked, canoed and camped, visiting almost every part of the country, the mountains of Romania still remained a mystery. We had seen them only from the road and the tourist literature gave us no clue as to then potential.

With the 1989 revolution and the fall of Ceausescu we were encouraged to return and now, with reduced restrictions, some mountain wandering was to be part of our schedule. Our Bucharest contact was Nicolae, an opportunist and a rogue without doubt, but a man of great charm and useful influence. He had been no party member he emphatically declared, notwithstanding his residence in the exclusive and restricted Bulevard Primaveri exactly opposite Ceausescu’s former palace. For the first time he was now free to invite us to his home.

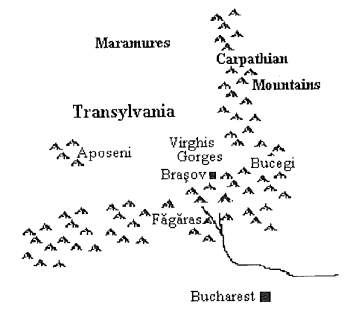

Nicolae was eager to plan our itinerary and to join us for the first few days of our journey. Along with his wife Gina, in a car already overloaded with food and a mountain of goods for some needy orphanage, we set off for Transylvania. In the land of fortified churches to the north of Brasov, we left the village of Virghis to drive ten miles in bottom gear along a rough track, marked on no map, and probably where no private car had been before. We made camp beside the piirnitive dwellings of some charcoal burners.

It now appeared that the chief object of this tortuous journey was less to show us the splendid scenery of this remote comer of Romania but to allow our dubious friend Nicolae to fish in a river little fished before. He and Gina disappeared until dusk up some steep-sided limestone gorge, but not before taking us to its chief point of interest.

This was the dark opening to a cave reached by a scramble up the wall of the gorge. At its mouth stood a memorial stone to two cavers who had entered here some years earlier never to be seen again. Nicolae, who lives in a fantasy world, told us in all seriousness that this was the opening from which emerged the children following the Pied Piper of Hamelin.

“For he led us, he said, to a joyous land

Joining the town and just at hand”

That accounted, he said, for the large German-speaking Saxon population in these parts.

“And I must not omit to say

That in Transylvania there’s a tribe

Of alien people that ascribe

The outlandish ways and dress

On which their neighbours lay such stress

To their fathers and mothers having risen

Out of some subterraneous prison.”

We were limited for time but this little visited area of the Virghis Gorges offers great opportunities for the walker and, no doubt, both the cragsman and the caver, but facilities are few and maps, information and guidance, lacking or of little use.

We were to travel north-west making for our favourite Transylvanian province of Maramures where a rich peasant culture is still a living thing which forty-five years of Communist rule and Ceausescu’s destructive megalomania had failed to destroy. On a Sunday we watched the wooden churches fill with worshippers colourfully garbed in extravagant hand-made costumes. On the following market day the scene was even more colourful and vaiied with the addition of gypsies, horse dealers, shepherds, craftsmen and traders.

We stayed in the hotel at Sighetul Marmatiei where $50 was demanded for a spartan room dimly lit with one 40 watt lamp. The coarse sheets seemed doubtful and there was no hot water and, after 9 p.m., no water at all. Most of the items on the menu were off, there was no beer or wine, only a sickly sweet fizzy pink pop. We soon transferred ourselves to a private house where at a fraction of the cost, but still paid in treasured dollars, we were wairnly welcomed and cosseted. When we departed it was with affectionate embraces and bearing then gifts of local handiwork.

The rounded mountains of Maramures rise to 2000 metres and extend east to the Bistrita valley down which we had canoed some years earlier. They give splendid wahking and a few mountain huts offer basic accommodation. But ours was but a brief visit; our aim now was to walk in the more challenging range of the Fagaras, the highest in Romania.

On our journey to them we revisited another little known area of limestone peaks and valleys, the Apuseni. We remembered this area from some of our early travels in the sixties, where there still existed in the villages the old tradition of spontaneous hospitality and the best room in the best house would be willingly vacated for the strange foreign visitors. On this last occasion we accepted hospitality at the Orthodox Monastery of Remetz, beautifully situated below the cliffs of a steep-sided limestone gorge. By tradition such hospitality is offered free but a donation to the Order is willingly received and, if paid in dollars, the nuns will no doubt pray for your welfare with even greater fervour.

Driving east from Sibiu we could see the great wall of the Fagaras rising steeply from the plain like the Cairngorms from the Spey valley only higher. We spent the night as the guest of the Father Superior of the Monastery of Brincoveanu, the next morning walking for several hours to the mountain hut, the Cabamet Valea Simbetei.

The Romanian Alpine Club, first formed in 1934, was dissolved in Communist days to become just another State controlled federation. Now restored, although lacking in funds and resources, it is eager to build more mountain huts, acquire proper equipment and make foreign contacts. Some of its members were sitting outside a mountain rescue post close to the Cabarnet. As we walked past they hailed us with delight for, while all others were garbed in track suits and trainers, we alone were properly booted and clad as mountain people should be. Perhaps to test my prowess I was promptly invited by one of its members to walk and scramble to a high col at some 2000 metres.

As people from the West we were regarded with some awe and curiosity and that evening we were surrounded by university students most speaking good English or French. They questioned us eagerly as if we were prophets from another world, a world that few of them could easily visit for economic reasons if no longer political ones.

We were to return to the mountains some weeks later with our Bucharest friend Cristina Goran, herself a mountain walker. This time we visited the Bucegi massif, the most important climbing area in Romania. As we walked up to the Cabarnet Poiana Izvoarelor we faced a long, almost unbroken line of steep limestone cliffs. While some noteworthy routes have been made up this face, many other possibilities remain.

Cristina knew the warden and arranged that, for a few dollars, we would enjoy favourable service and also, at that time, those most rare of Romanian commodities, beer and wine. These were brought up by mule and here remains a profound mystery. While the great tourist hotels of Sinai and Busteni could seive only the revolting pink pop why, we wondered, in a simple hut halfway up a mountain could you, if you so wished, get uproariously drunk? Whatever dubious dealings were the cause, news of this plentitude spread far and wide. Following the mule there came a procession of gypsies and other hard drinking types toiling up from the valley bottom There was much boisterous behaviour and some fighting that night.

With Cristina we made several pleasant excursions on the terraces below the cliffs and, on the final day, I made my only noteworthy ascent. This was to the summit of Omu, 2507 metres, the third highest mountain in Romania. I did it with a young Romanian boy who claimed to know the way. After several hours of forest path we tackled the face more or less direct by generally easy scrambling. Such difficult passages as there may have been were protected by fixed ropes. In six or seven hours we came out on to the summit plateau. The descent was north by an easier but much longer route and through a valley of spectacular limestone cliffs.

In climbing Omu I was not the first YRC member to make the ascent. Employed in some special war time service, the late Harry Watt described his ascent in 1940 in No. 24 of our Journal. He called it “Omul: or Getting Fit for War“.