The Trou de Ver Project 1993-1995

Ged Campion

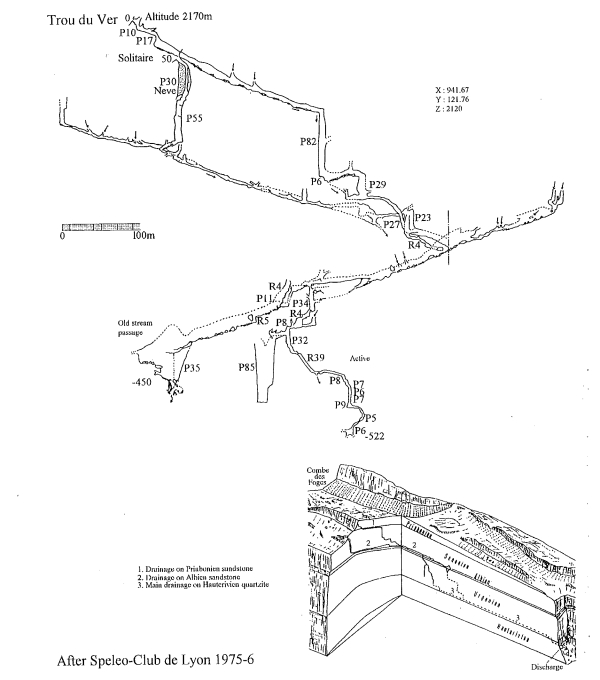

In the Combe des Foges, high above the cliffs of the Torrent de Salles, a small, rather insignificant hole emits a strong draught. Indifferent to the ferocity of winter storms, the draught is just warm enough to keep the cavity open even in the heaviest of snows. The hole is the entrance to the Trou de Ver, discovered in 1974 by Richard Maire of the ‘Speleo Club, Lyon’, and pushed to a somewhat inconclusive depth of minus 522 metres in the winter of 1976.

It had never been our original intention to explore this cave system, but in 1992 plans to make a winter descent of the Gouffie Mirolda were thrown into turmoil when Anglo French relationships reached an all time low. The ‘Club Ursus of Lyon’ somewhat insistently refused to grant us permission to explore the Mirolda. This had been a grave disappointment to all concerned since a considerable amount of time and effort had been spent preparing the expedition. Even a reconnaissance had been made in November 1993, to locate the exact whereabouts of the entrance so that no time would be wasted searching the mountainside in difficult winter conditions.

It was during this reconnaissance that Stewart Muir and Jon Riley ventured onto the cliffs above the Torrent de Salles for purely speleological interest and decided to locate the entrance to the Trou de Ver. In fact two entrances were located at that time, the other being the Puits de Solitaire. It was from that moment that the exploration of the Trou de Ver would inspire Stewart Muir and, the following year, the rest of us to plumb the depths of this relatively unknown system. Although at first viewed as second best to the Mirolda, the Trou de Ver quickly became a tour de force itself – and so the saga of its exploration unfolded.

Many of the cave systems on the Grand Massif, south East of the Mont Blanc chain have to be explored during the winter. Their high flooding potential caused by melting snow from glaciers during the summer months makes exploration impossible. The only safe time to descend these systems is during freezing winter conditions when there is virtually no danger of flood waters entering the systems.

In January 1994, therefore, two well equipped teams headed for the snowy Grand Massif. Even as they left England some members of the team were still unaware of then actual objective, believing that our focus would be on the Mirolda, others more aware of the Anglo French problem were safe in the knowledge that any attempt would be folly. Two chalets were established as a base camp in Samoens – the first a rather old French alpine house and the second a puipose built, though stylish, studio belonging to Madame Rouge. In the ensuing days the team made various journeys from Samoens to Flaine. This approach was chosen because of the dangerous avalanche conditions above the Torrent de Salles. From Flaine the route was made even easier by accessing the Telepherique des Grandes Platieres, which gives access to the Desert de Plate. Once on the summit of this plateau ski mountaineering is the only effective method of venturing to the Combe des Foges where the entrance is situated.

This requires traversing the col between the Tete Pelouse and Les Verdets. Once through this col the ski down through the Combe des Foges was idyllic over untrodden snow to the entrance of the Trou de Ver precariously perched above spectacular cliffs.

Back at the Trou de Ver enough equipment was assembled to enable Stewart Muir, Graham Salmon and myself to descend and at least rig the first 2 vertical pitches. The entrance pitch had already a rope in place, faded and worn by ultra-violet rays over the years, clearly too dangerous to rely on. We descended through the awkward entrance slot on our own rope. The 10 metre shaft quickly bells out to reasonable proportions to a level floor. Although we did not realise it at that time, this was to be an ideal storage place for our equipment for many months to come. The way on slid away under the chamber wall requiring crawling to a passage of larger dimensions, ending at the top of the second pitch. Ten metres below a large breakdown chamber slanted away ramp-like into the darkness. This was the start of the long descending gallery that would take us to minus 100 metres and to the top of the ‘big pitch’ of 82 metres, jealously guarding the access to the lower reaches of the Trou de Ver. With a few rope bags assembled at the top of this pitch, this was to be the limit of our exploration that day.

Conscious of our return journey we headed back to the surface to make the most of what daylight we had left. Our companions anxiously awaited our return at the entrance, already firmly attached to their skis and ready to leave. After a short debate, a somewhat unwise decision was made to descend the Combe des Foges to its lowest reaches and eventually reach Samoens by a series of ridges and interlocking valleys. The epic nature of this descent is a story in itself. The journey was to take some 8 hours through avalanche hung country and traversing precariously in darkness on cliff edges high above the Giffre Valley. Like a small army in retreat we ebbed our way through snow clad pine forest to a horrendous steep descent to Samoens itself. When we eventually arrived back at the chalets we discovered that the team on the Aiguille de Briou had barely forged a trail halfway to the Chalet de Criou. The sheer depth of snow and absence of skis had made their progress impossible. They had to bivouac out in goat sheds near the Chalet de Trot and had planned to return to the village the following day.

After a good days rest and with the two teams reassembled, it was decided that an all out assault would be made on the Trou de Ver. With equipment in place, it seemed that we had eveiy chance of success and by caving standards a depth of minus 500 metres did not seem unreasonable. Those individuals without skis or unable to ski were equipped with snow shoes to combat excessively deep snow. The following day therefore, saw the teams assembled at the surnrnit of the Grande Platieres. But to our bitter disappointment the weather had deteriorated to such an extent that it was felt unwise to attempt to find a way over to and down the Combe des Foges. The trip was therefore, abandoned and eveiyone returned to Flaine. Storms raged for the following 2 days and the prospect of our being unable to retrieve our equipment in the cave quickly became reality. Running out of time, we left the snowy Samoens to return to England with virtually half of the caving arsenal still in the high Alps.

Tn May the same year a small but detenriined group of cavers returned to the Grand Massif Inexpensive but luxurious lodgings were secured in the village of Les Carroz and the team anxiously made preparations to return to the Trou de Ver in the hope that the equipment would be still in place. In due course we were ascending through green sunny alpine meadows that only months ago had been suffocated by snow. Above an altitude of 1600 metres the slopes were still snow bound and skis were necessaiy to climb up to the col guarding access to the Combe des Foges. On arriving at the entrance we anxiously descended the first pitch elated to find our equipment had not been removed. Indeed, everything has been left in place, although we were a little surprised to discover that a rodent had been nibbling through numerous pahs of Wellington boots yet had left our food supplies untouched!

Although we knew it would be virtually impossible to descend the cave at that time of year, we forlornly made our way to the top of the 82 metre pitch to assess the water levels. As expected the pitch was taking a steady flow of water and making any prospect of descent suicidal. To be caught on a pitch of this size with even a slight increase in water would be a very daunting prospect.

With only 4 in our team, carrying the equipment back up the Combe des Foges and down to Flaine was a Herculean task to say the least. Even the most seasoned skiers in the team were experiencing difficulty in making stylish telemark turns with such heavy packs.

The Trou de Ver had defeated us quite decisively and the humiliation of having to abandon our equipment was a bitter pill to swallow. However, like many exercises in climbing and caving, the experience of defeat can often strengthen resolve to return better prepared next time. Therefore, completely ignoring the old adage of ‘once bitten twice shy’, rather than being dissipated, interest in the Trou de Ver increased.

Therefore with the onset of another year came new hopes and in the Christmas of 1995, a smaller, light weight and more refined team were assembled. Equipment was kept to the bare minimum, 8 mm ropes were chosen in preference to 9 mm ropes, and 9 mm ropes in preference to 10 mm ropes. Accommodation was arranged in Flaine itself to reduce any need to travel snow bound roads. Almost carbon copy like and like an offering to the Gods, all the equipment was ferried up to the cave entrance on the first day. The Combe des Foges seemed even more enticing and magnificent than the previous year. Snowy hillocks had welled up above the mterlocking canyons and runnels forming ways through the terrain.

A route was carefully chosen and we skied across to the cave entrance. This time it required a degree of excavation but the blow hole feature of the Trou de Ver remained true to form. Pleased by our day’s progress, we returned to Flaine to make preparations for the grand descent.

We woke the following morning to a beautiful day. Spirits were slightly dampened by threats of further snow later on in the day. Would this render the Combe too dangerous we feared -not allowing an escape either down to Samoens or back up to the Tete Pelouse? But too much time, sweat and preparation had already been invested in this project and success was feverishly close if we could just focus in on the caving aspect of the trip. While we caved deep into the night we would be indifferent to the alpine storms raging on the surface.

Myself, Bruce Bensley and Graham Salmon arrived at the entrance that afternoon mindful of the arrival of more snow. We anchored our skis near to the cave entrance and quickly descended the entrance pitch. Our progress to the top of the ‘big pitch’ was swift. Once through the slot at the top, the enormous size of the shaft exceeded all expectations. We had dreamt of this place for a year but had been denied access to its secrets until now. The void was huge, an incredible 82 metres free fall – the sides of the shaft at times barely discernible in the inky darkness. This huge drop had been forged through the Senonien Shale, a stratigraphy which seemed to be reminiscent of biick work lattice. On arriving at the bottom of the shaft only the faint glimmer of the caver’s light above could be seen as he embarked on a spiralling journey.

Unfortunately our raptures over the pitch were quickly brought to earth by the toil that lay ahead. A less grand passage led on to a pitch which was to herald the beginning of a succession of muddy shafts. The often less than vertical nature of these drops hampered progress causing rope bags to snag. Pitch after pitch caused problem after problem Re-belays were often difficult and at times ropes frorn previous French expeditions left in place, became entangled in our own ropes. It was with relief therefore that we dropped out of a small window eventually in to the Collecteur, the mam stream passage – though absent of any sizeable stream at minus 288 metres. At this point we estabhshed a bivouac and brewed up.

The potential for flooding at this depth was evident – a place a caver would not want to venture during the summer months. In winter you were at least safe in the knowledge that only a drastic rise in temperature outside could cause difficulties and this was highly unlikely in the snow bound Grand Massif in January. Nevertheless the caving had taken it’s toll on us and the weight of caving rope bags had required a redoubling of our efforts to reach this depth.

The morale of the team was low – our situation seemed remote and our backup was negligible. Slightly refreshed by food and drink we ventured on crossing deep pools and strange but beautiful mud formations at a depth of minus 300 metres. We soon encountered huge drops that required awkward traversing without the aid of a safety rope. It was decided that I would continue alone to try and find the top of the 34 metre pitch which would mark the beginning of the more constricted part of the cave.

After approximately 10 minutes and with seemingly httle effort, I reached this exact spot. An old French in situ rope was belayed at the top and disappeared into the darkness below. In the circumstances I was not prepared to descend alone and decided to return to my companions who had by this time already made the decision to return to the surface. It was therefore with a mixture of feelings of disappointment and relief that we slowly started back up the series of muddy pitches. At the bottom of the 82 metre pitch we drank soup and cooked a meal before embarking on the vertical climb above us. The actual pitch turned out to be less thing than we had anticipated but pulling the tackle up behind us was. With an intricate method of pulleys and stops all rope bags were successfully pulled to the entrance pitches. Weighed down with rope bags it was like climbing the side of a mountain.

Having ferried our equipment back to the base of the entrance pitch, Bruce was the first to ascend the rope. He was greeted at the surface by swhling spindrift and howling wind. We later discovered that it had been snowing for almost 12 hours! Our moist caving suits soon began to chill and our damp harnesses around our waist froze to a cardboard consistency. The prospect of hypo-thermia was ever-present in our minds. The weather-was so bad that we only had limited visibility. For a moment Brace thought that he could see the Tete Pelouse appearing and disappearing in the distance through swhling mist. On closer examination this apparition was nothing but a small snowy hillock only yards away from the entrance! We were faced with a dilemma. If we decided to sit it out we would have insufficient food supplies and warm clothing to last indefinitely. Besides, how long would it continue snowing, hours or days? The more snow that fell the greater the prospect of avalanches on the Tete Pelouse, the obstacle that separated us from our warm beds in Flaine.

In a spirited fashion we donned our skis and only carried light weight emergency packs. We would retrieve the rest of our equipment during the following days. Therefore rope bags were left at the bottom of the entrance pitch. It has snowed so much that it appeared to have changed the very terrain with which we had become familiar – the small intricate system of snowy canyons were difficult to identify in the almost white-out conditions.

Choosing a line and leading off I cut the side of a seemingly innocuous easy angled snow slope. Almost instantaneously, but in slow motion, the whole slope slid nonchalantly away, taking me with it.

Only metres down the slope the slide stopped as quickly as it had started. I was unhurt and my head and shoulders were still above the snow. I was bent over by the sheer weight of snow and my skis had acted like belays on my feet, locking me into a position where I could not move my legs. The veiy article that could lead me out of this snowy hell had trapped me. I feverishly dug towards my feet to release my bindings but my contorted position prevented me from releasing the binding on my left ski. Bruce and Graham appeared to be looking on helplessly like shocked bystanders. I surveyed the slope above me hanging in deadly silence. Would it continue to slide and completely engulf me I thought? By now Brace and Graham had jettisoned their skis and waded into the deep snow and began furiously digging at my feet. I was free in a second but one of my ski sticks was still missing. To continue without it would seriously impede progress but this wasn’t the place for a stop and search. Luckily in minutes Bruce located the missing article and we both straggled back to a position of relative safety.

We were all visibly shaken by the experience, Brace and Graham never having witnessed an avalanche victim before! Again we were faced with a dilemma, should we carry on up the Combe or go back to the relatively safety of the Cave? We were only 10 or so minutes away from the entrance but it was snowing so furiously that our ski tracks were completely covered. We had visions of wandering too close to the slopes adjacent to the cave entrance which hung precariously above the cliffs of the Torrent de Salles. It was with this in mind that we decided to continue up the Combe to take on the challenge of the Tete Pelouse and attempt to cross the col to Flaine.

Fatigued by twenty-four hours of caving and ski mountaineering, somehow we accelerated up the centre of the Combe with purpose. Despite the poor visibility I felt I had visited this place often enough to know its intricacies, moods and deceptions. Before long I could just make out an old wooden post, perhaps a marker from bygone days: a detail we had ah remembered. It was still high above the snow line, unchanged from the day before. Immediately I thought, this augured well because it meant that the snow on the slope above us had not been subject to the same accumulation that we had witnessed lower down in the Combe. We confidently climbed towards the top of the col and in reaching it experienced a great feeling of relief All that remained was to find our way along the small ridge and then the route down onto the piste which would lead us to Flaine. Far below us we could hear the sound of explosions, an attempt by piste workers in Flaine to create controlled avalanches to avert the accumulation of snow above the village. We gradually descended below the cloud line and could see the village below. Piste workers were bemused to see us ski by in such appalling conditions. However, after questing where we had been and realising that we were Speleo’s, they were satisfied by the explanation.

Graham crashed out in the apartment and Bruce and I fell asleep over a beef burger in one of the cafes. The rest of the team had gone shopping in Cluses.

For the next two days the weather continued unsettled and avalanche risk closed the piste. Going to the Combe des Foges was out of the question. As for the equipment left in the cave, we felt confident that we had a plan to secure its return. After our experience the previous year we were not going to be caught out again. Discussions had taken place to use the seivices of a local helicopter pilot since the weather forecast was for an improvement on the Saturday of our departure. We felt that we could just do it in time. The ignominy of having to leave our gear again was unthinkable and we were adamant that the cave would not deny us what was rightfully ours, or so we thought.

On Saturday morning we awoke to a beautiful alpine day, not a whisper of wind or a flurry of snow. The mountains were clad in a deep pristine cover of snow. The helicopter seemed ready and the cash payment had been settled but then, to our absolute hoiTor, the pilot casually announced that it would be unsafe to attempt to land or even hover in the Combe des Foges. There was simply too much snow around. The deal was off and it would be with disbelief that people would listen to our stoiy when we returned to England, and indeed they did.

In the following May we returned to France as in 1994. The gear was retrieved and the project’s stalwart members agreed that they could not subject themselves to this humiliation again. With some sadness the Trou de Ver project was definitely over. Time and effort expended on such an apparently small hill in retrospect seemed quite puzzling. The full might of two well equipped expeditions had been completely thwarted.

The dangers of high alpine caving in winter cannot be emphasised enough. The remoteness of entrances and the commitment to venture deep underground with minimiim support is more than most cavers would be prepared to take on. Those involved need not only to be cavers but mountaineers experienced in the full range of winter skills. It remains to be seen whether the Trou de Ver will ever receive a descent from British cavers and if any of the members of this expedition will be amongst them.

I suspect the latter is unlikely.

Those involved in the project were:

Ralph Atkinson

Bruce Bensley

Ged Campion

Joel Corrigan

Alan Fletcher

John Martin

Stewart Muir

Shaun Penny

Peter Price

Jon Riley

Graham Salmon

Mike Wooding