Yorkshire 2000’ers

Patrick Henry

Every May I become afflicted by a primitive urge to go on an intemperately long walk. I recognise the symptoms and have tried to suppress them; I have even fancied myself cured, but the urge has only been dormant. When I limp home and contemplate the wreckage of what had been a perfectly respectable pair of feet I always vow that I will never do it again, but, having a selective memory I recall only the pleasure and blot out the pain.

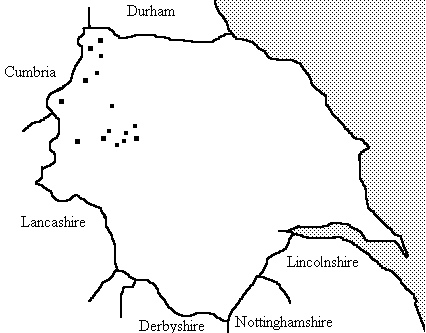

A couple of years ago I decided with my brother-in-law, Peter, who can be persuaded to do anything, to attempt what are rather grandly known as the Yorkshire Two Thousanders, although all the tops are within the North Yorkshire boundary. The walk follows a rough circle and the distance, I am told, is “roughly” 115 miles. I take it that the “roughly” allows for becoming lost in cloud or blundering hopelessly in the dark wondering whether you are on Ingleborough, Pen-y-ghent, Whernside or any of the three. The walk passes through much familiar country, the Three Peaks, and the hills of Wharfedale as well as the almost untrodden ways between the head of Bishopdale and Dodd Fell, and the remote and beautiful country to the north of Swaledale. The going underfoot is good for much of the way but there are longish stretches of the very worst that Yorkshire has to offer – high, almost flat and featureless expanses of tussocks, peat hags and heather which sap the energy and across which you crawl like an ant on wrinkled velvet. We were very fortunate to hit the middle of a long rainless spell, as I think wet feet and waterlogged ground would have defeated us.

I decided to attempt it, if not in two days, then two unbroken sessions. I realised that it must involve walking through at least one night and chose midsummer night when they will tell you the sun barely dips below the horizon and that you can read the telephone directory at midnight, though I know better having spent the early hours of the morning stumbling around in inky blackness.

I decided that it would help to choose a familiar and straightforward stretch of country for the night time section and what better than the long ridge of Great Whernside, down to the head of Coverdale and the length of Buckden Pike to the head of Bishopdale, guided by an obliging wall for much of the route. Although, as the route is circular, we could have started at any point I calculated that if we were to start at the Hill Inn at three in the afternoon and walk to the East it would bring us to Kettlewell at nightfall.

We left the Hill Inn at 3.00pm on 21st June. The first part was easy and Ingleborough and Simon Fell were soon behind us as we raced through Horton over Pen-y-ghent; Plover Hill, Fountains Fell and Darnbrook Fell followed, and in failing light we dropped into Litton and straight into the pub followed by clouds of midges intent on draining our last drop of blood. So confident was I at this point that I was wondering whether the walk was too easy and should we have attempted something rather more challenging? Had I been right to drag Peter 300 miles from his comfortable home in Dorset simply to romp over a few paltry hills? We met a party of other walkers in the pub who had walked from Arncliffe, and we breezily mentioned that we had come from the Hill Inn and that our next stop would be Muker.

Rejoining the midges waiting in the car park, we set off up Birks Fell all of 2001ft. We soon shook off all the midges who, deciding after all not to join us for the next leg of the journey, turned back to Litton, leaving us to walk the length of Old Cote Moor Top.

We came to Kettlewell around midnight and still bursting with optimism, set off up Hag Dyke to the top of Great Whernside, and as we laboured over the shoulder an uneasy feeling came over me that perhaps this wouldn’t be quite such an easy walk after all, and that we should rein in and start to pace ourselves for the long hours stretching ahead. The fact that Great Whernside is shaped like the back of a whale and has several summits, each indistinguishable from the other in the dark, is no help to navigation, but with the help of a compass before too long we arrived at the head of Coverdale and set off over Buckden Pike.

For the first time Peter, who had been giving off noises like an Italian coffee machine for some time, announced rather gloomily that only a complete blood transfusion and three weeks in intensive care with round the clock nursing would save his life, but after a mixture of threats and cajolery he agreed to carry on. It is always darkest before the dawn and, as we approached the top of Buckden Pike, the sun rose on a glorious day with absolutely clear views west to the Lake District and east to the North Yorkshire Moors. Peter was revived by a five minute sleep on a patch of damp heather and the remains of a sandwich from the day before. I woke him with a reminder that life is not all pleasure; he leapt to his feet and set off with indecent haste to the head of Bishopdale. We then started what proved to be the most exhausting and dispiriting part of the journey.

On the map the section of country between the head of Bishopdale and Dodd Fell looks innocent enough. The land is flat, free of any prominent features and rises to barely 2,000ft, at a point I had never heard of previously and hope never to again, called, I think, Middle Tongue. There are no tracks and it is an almost flat expanse of tussock and heather with hags and long furrows in the peat. There is nothing more tiring than walking across such country either knee deep in heather, goose stepping over tussocks or weaving between peat hags. The top itself is insignificant, a single white pillar of concrete like a whale’s tooth on a flat moor visible from miles around. Walking towards it is like marching on the spot, as time seems to stand still and one gets no closer. By now the day had become hot, the slight tenderness in my feet had become much more painful and the twingeing pain in both knees distinctly uncomfortable. Each ridge promised to be Dodd Fell but proved to be something less significant, and miles still lay ahead.

We eventually reach Dodd in mid morning, the weather still glorious and the hill covered with cotton grass. From there was a short step to Drumaldrace and then down into Hawes to a cafe serving chips with everything, giving off a rich smell of frying which I had until then always passed with a shudder. It was after midday when we set off footsore, hot and tired for Lovely Seat and from there down by the Butter Tubs and on to Shunner. The squelchy, liquid peat which usually coats Shunner was, in the middle of this glorious summer, dry and springy and having finished the long slog to the top, the gentle decline to Muker in the cool of the evening was a delight. We must have looked a sorry sight as we walked into the pub as a woman, clearly deeply moved by our pitiable condition, gave up her seat to me. A pint of beer followed rapidly by two more and a plate of sausages had a magical effect, reviving me like a watered flower.

We were to spend the night in a camping caravan which we had left the day before in the car park in Muker, and I barely remember removing my boots before falling asleep. I woke early feeling stiff and sore, realising that a day’s walking of almost equal length lay before us. Having looked at my feet, both decorated with weeping blisters and swollen toes, I really doubted whether I would be able to finish; but half an hour’s walking is marvellous therapy, and as we made our way up Swinner Gill the discomfort evaporated, I began to feel quite elated and almost persuaded myself that I was enjoying it.

Rogan’s Seat is scarred by a hideous yellow road now, after some years, beginning to take on the colour of the surrounding moor. For once I was grateful for this road which led us from close to the top of Rogan’s Seat most of the way to Water Crag. From there to Coldbergh Edge is a long stretch of remote, high and beautiful moorland where you may be lucky, as we were, to see a hunting short-eared owl. To the North you can just see traffic crawling nose to tail over Bowes Moor on the road from Scotch Corner to Penrith. There is no trace of any path here, the ground is rough and uneven making for painfully slow progress. The morning, fortunately, was clear and cool and above all the ground was dry and we were able to walk for much of the way along dry beds of peat between hags, sticking our heads up from time to time to make sure that we were heading in, more or less, the right direction.

The ridge of Coldbergh Edge seemed to get no nearer and it was already late morning. Had we continued at this speed we would never have finished but eventually, arriving at the top around noon, we came to a well trodden path which led down to the very top of Swaledale where the land falls away sharply to Kirby Stephen. From there the climb to Mallerstang Edge is short and steep, but the remainder of the ridge is a long and undulating walk over good ground with magnificent views of Wild Boar Fell and the comforting knowledge that all 2,324ft of it are firmly planted in Cumbria. We now made rapid progress and it seemed no time at all before we dropped down from Sails in time for tea and scones at a farmhouse at the bottom of Swarth Fell Pike.

I now began to feel that we were in sight of home, and the short steep climb to the top of Swarth Fell Pike was easy, followed by the long gentle decline to the Moor Cock. I burst into the pub with my tongue hanging out longing for a drink, to find myself queuing at the bar behind a man ordering six of the most obscure cocktails for a party of women, and who couldn’t make up his mind whether to have mild or bitter. I would cheerfully have strangled him to get to the front of the queue. It is a mistake to sit in a pub in the early evening when you still have several miles ahead of you, as it saps your enthusiasm and you have to fight down the urge to fall asleep. We left, however, after half an hour and at about eight in the evening stopped at a telephone box to ring my family to say, with incurable optimism, that we had nearly finished and would be home soon. I had not reckoned with the hideous stretch of road which lay ahead, with a short but tiring walk to the top of Great Knoutberry Hill, then down past Dent Station, almost into Dent and onto the steep road up Deepdale. I was wearing the most comfortable boots with a padded insole but they presented no barrier to the unyielding surface of the road.

We reached the foot of Gragareth at about midnight hungry, thirsty and tired and for the first time the weather, which had been perfect until then, broke producing a gentle drizzle. Stumbling around on Gragareth in the dark is no fun at all. On clambering to the ridge I lay down exhausted, heedless of the gentle rain pattering down on us. This was the shortest night of the year and by the time we were down Gragareth and starting up Whernside it was almost daylight. Whernside was in cloud, and as we were now very tired seemed to go up for ever, but eventually we came to the top at about four in the morning leaving only the walk along the ridge, down the hideous wooden staircase on the North side, and a further mile to the Hill Inn. From there we drove back to the caravan in the car park at Muker, and this time I did not even remove my boots before my eyelids clanged shut and it was all over.

I thought I was reasonably fit to undertake this walk but I found it a major test of endurance, and the worst part was wear and tear on my long suffering feet which took a week to recover. Most people to whom I mentioned it thought I had finally taken leave of my senses, and that I should know better at my age. The walk took a total of 52 hours, which sounds a long time to walk 115 miles, but at times because of the difficulty of the country, we moved very slowly, and had the ground been wet we would have taken much longer. It is, however, a marvellously satisfying feeling to have walked up every top in Yorkshire over 2,000ft. I am told there are 26 – if I am wrong and have missed one out, please do not write and tell me – because I shall have to do it again!