More Eastern Rambles

George Spenceley

“Don’t go to Bulgaria,” people had advised. “The economy is in chaos, the infrastructure has collapsed, crime and corruption are rampant.” Even the Yugoslav border control officers seemed doubtful and marvelled that one so old should be so foolish as to enter a country seemingly in such total disorder.

Certainly at the Bulgarian border we felt not all was well. Our enquiry about motor insurance was received with a nod of the head, meaning precisely the opposite of what one expects; a shake of the head here means yes. If not pre-warned this reversal of custom can wreck your sense of reality. We pointed to the insurance office across the road but there were more vigorous nods and indeed the place was barred and bolted as if unused for years. We never did get insured – this in a country of manic drivers.

We were, during 1997, to travel in our VW Camper round the Sofia ring road with its ill marked crater-like potholes in search of an official camp site. To camp wild in Bulgaria is to risk severe penalties although no doubt a few dollars would settle the matter. The camp site had ceased to exist, as had most of the others we were soon to learn. It was late and dark, but a friendly police officer – yes, they can be friendly, no longer the stony-faced officials we earlier had learnt to avoid – directed us to a guarded TIR park. Here we were given a corner beside a suburban railway platform, much to the curiosity of the early morning commuters.

The next morning we drove to the Rila Mountains, a popular area for both skiers and walkers. We were fortunate in having a large scale map of the range, with Cyrillic lettering of course, but with trails and mountain huts (or hizhu) all clearly marked. If you require the best available map of almost any obscure place in the world, Pacific island or Polar coastline, it’s likely you’ll find it in The Map Shop, unlikely situated in the small town of Upton-on-Severn. Their world coverage is enormous but while you may buy a map of Crozet Island or a town plan of Kano, of Romania, our next country, they had nothing. It seems the legacy of Ceausescu’s paranoid security lingers on.

We drove to Borovets, once a place of lavish villas and hunting lodges, the exclusive playground of the rich. Later it was to become nationalised for the benefit of union leaders and Party members. Now in early June it was almost deserted, suffering between-season gloom. The skiers had departed, the walkers and climbers had yet to come. Again it was to be a case of ambitious plans reduced to modest achievements. Rising steeply above the town are the slopes leading to Bulgaria’s highest mountain: Mount Musala, 2925 metres; but the hizhu was closed and the snow soft and wet.

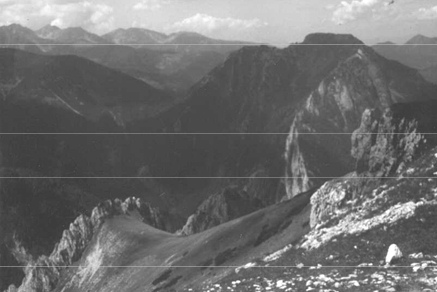

Instead we crossed to the valley of Cerni Iskar where village life, with its bullock carts and donkeys, has hardly changed through the centuries. At its head is another resort, Malyovitsa, likewise suffering between-season gloom. By way of a reconnaissance we walked to the hizhu of the same name through several miles of silent pine forest; such is the rather gloomy prelude to any mountain walk in these parts. When we did break out close to the hut it was to see extensive snowfields beyond, bounded on each side by substantial rock buttresses. These offer good rock climbing for we were later to see photographs laced with dotted lines marking the routes.

A poster beside the hut showed us that we were now on the European ‘E4’ trail starting an unthinkable way to the west in the Pyrenees. Who has the leisure and enough dedication to complete the lot, we wondered? Patrick Leigh-Fermor, absconding from King’s School, Canterbury, had of course done a similar trek, and then we thought of Nicolas Crane’s recent journey. Much harder on himself, Crane walked Europe’s mountain backbone from Cape Finisterre to Istanbul, splendidly described in Clear Waters Rising. Perhaps Crane had stayed in this very hut. We remembered too that Bulgaria was the only country where someone took a pot shot at him.

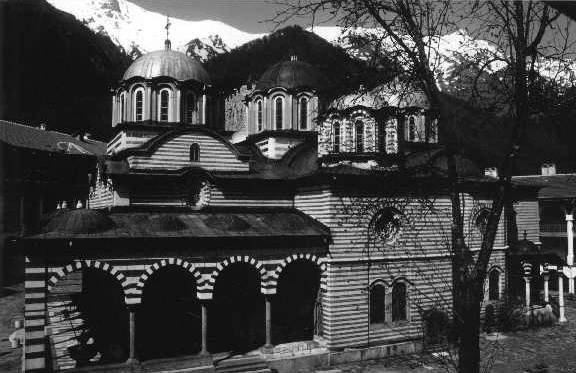

The classic trek from Malyovitsa is across the range to Rila Monastery. It was only when a very tired trekker slowly plodding toward us said that it had taken him five days to cross, and pointing to his knees indicated the depth of snow, did I accept that another ambition must be reduced to a more modest achievement.

This more modest achievement was to be the summit of Sahtrovitsa, a good viewpoint but a mere 1650 metres and, if it was the first British ascent as almost certainly it was, it can only be because of its almost total insignificance among a profusion of peaks more glorious. Above the forest and on the lower pastures we met a shepherd who for some obscure reason was raking out molehills. Delighted and surprised to learn that we were English he warmly shook our hands, and did so again when we departed. The warmth and friendliness of the Bulgarian country people are qualities we have noted many times over the years.

A mountain range rather less in height but greater in length is the Stara Planina. This is the real backbone of the country, extending more than 500 miles from the Serbian border to the Black Sea. On the way to it we paused in Kazanlak to change money. The Balkanbank was closed but we met the English-speaking former manager, now the night-watchman. The bank had gone bust.

We camped at the summit of the Shipka Pass where, in 1877, a combined Russian and Bulgarian force had fought against the massive Ottoman army below, throwing boulders and even bodies at them when their ammunition was exhausted. The top of the Pass was a splendid base from which we made long excursions both east and west along the undulating ridge, following the waymarks for the European ‘E3’ trail. Here’s another trans-continental route for anyone with a year or so to spare.

Border crossings in East Europe can be a prolonged ordeal. Crossing into a Baltic State a few years ago we found ourselves at the end of an almost stationary line of traffic 12 km long. At another crossing a $40 bribe was demanded. We had been warned of horrific delays at the Romanian border and need for more bribes. In fact all went well except that we had to pay $7 toll, $5 for disinfection of vehicle wheels and, finally, $6 ecological tax – this in Europe’s least ecologically minded country.

With our Romanian friend Cristina it was a relief to escape without damage from Bucharest where the drivers act like kids with new toys and, for many, that is just what a car is – a new toy. The Carpathians which divide the country rarely rise much above 2500 metres, but they can offer a wilderness area the equal of anywhere in Europe. Central and highest are the Fagaras mountains, and if my ambition was to climb Moldoveanu, this was discouraged by a mountain guide friend of Cristina for reasons that were not made entirely clear: soft snow perhaps, or because he considered me too old. Instead we were to make for the Apuseni, further west but on the way visiting the Bucegi Mountains. In early war years this was the playground of our late member Harold Watts. They rise up from the Prahova Valley in giant limestone cliffs that would seem to bar any easy approach to the plateau above. But there are gaps, one of which took us in a long day to the Cabana Piatra Arsâ at 1950 metres.

In spite of many protestations we suffered the unfair discrimination so often inflicted on western guests, paying heavily for our basic accommodation, while Cristina paid only a fraction for her share of the same room. On the other hand our dinner for three with wine was only 78000 lei, or a mere £6. With inflation rampant, prices rise almost on a weekly basis; today there might be another nought on the bill.

The Apuseni, our next location, was a long day’s drive to the west. It’s an extensive limestone plateau, a little below 2000 metres, riven by great gorges and divided by forested valleys. This is classic karst country with all the associated activities, as yet hardly developed, of long distance ski touring or trekking, climbing and caving.

Our approach was through the Aries Valley, the lower reaches of which are served once a day by a narrow gauge railway. It’s not to be recommended; it takes five hours to complete the 93km journey. Minor steep-sided valleys extend into the mountains on either side, all inviting exploration. On another occasion we drove up to a village called Rimetea. That is the name given to it on the map but once there you would be well advised to call it Torocko for this is a Hungarian village, a little pocket of Hungarian craft and culture. Sadly, nationalism has reared its ugly head and there is little love between the two communities.

This village would make a splendid location for a few days, lying as it does below spectacular limestone spires and ridges offering a wealth of walks, scrambles and climbs. But the main Aries Valley offers attractions too, in addition to the scenery. “It’s real ethnic,” as the Americans would say. There are lovely villages and wooden churches and you’ll see itinerant gypsy families camping along the way, ragged, poor and dirty but highly colourful, the women with a wild dark-eyed beauty. Also you’ll see something of Romania’s heavy haulage industry: covered wagons pulled by teams of horses. They lack any form of brake and on the descent tow behind them heavy boulders balanced on old tyres to slow them down.

The focal point of the Apuseni region is the Padis plateau. Given time you can reach it on foot over several days following trails from east or west; with less time we reached it in several hours following a rough stony track just possible by car. The Cabana Padis was officially closed but Cristina had somehow gained permission for its use and, making it our base, we enjoyed several high level circular walks. One day we visited Cetatile Ponorului where the Ponor river flows through a massive gorge a full 200 metres deep before plunging into a great cavity. It was a seven-hour walk for us; given easy access this could be one of Europe’s great natural attractions with car parks and all the attendant tourist trivia. This is real caving country, with sink holes everywhere, streams vanishing and reappearing, all promising access to the huge systems that lie below the plateau.

Rather surprisingly the practice of caving owes much to a Romanian. This was Emil Racovita who, it is claimed, founded the world’s first speleological institute at Cluj University. There are several active caving groups in the country who would be delighted to cooperate with competent foreign visitors, particularly if they could help with gear. Members interested should write to the Racovita Institute, Str. Clinicilor 5, 3400 Cluj.

The plateau, high though it is, is not unpopulated for this is the home of the Moti people. They are highlanders who moved into the hills in the 18th century to avoid conscription into the Habsburg army. They now live throughout the year in scattered communities at up to 1400 metres, the highest settlements in Romania. We called at one such dwelling to buy goat or sheep’s cheese. The couple, their faces weathered and creased far beyond their years, welcomed us into their squalid, smoky one-roomed thatched hut. The man later came for payment to our camper and marvelled at its orderly interior and the wonders of sink and stove, taps and water.

Cristina departed for Bucharest but we made more forays into the mountains. We made an attempt on Viegyasza, the highest peak in the Apuseni but unusually the Cabana was unwelcoming and lacked food. We returned to the head of the valley to find an idyllic camp site. Wild camping is now legal in Romania and only once were we disturbed. A police car stopped but only to ask if we had problems, a complete reversal of previous police practice. With a few exceptions organised camp sites are best avoided in Romania. You may be deafened by pop music or political speeches booming across the camp; the loos are places of unspeakable horror, and packs of wild dogs may forage throughout the night.

We had more months of travelling and more mountains ahead, but that’s another story. We visited both the Low and the High Tatras of Slovakia, and the High Tatras again in Poland. A long traverse of the main ridge above Zakopane gave me my best mountain day.

Our final ascent, not a first British ascent I’m sure but one of the few, and this at last the highest top in the country, was Suur Munamagi: 367m in Estonia!